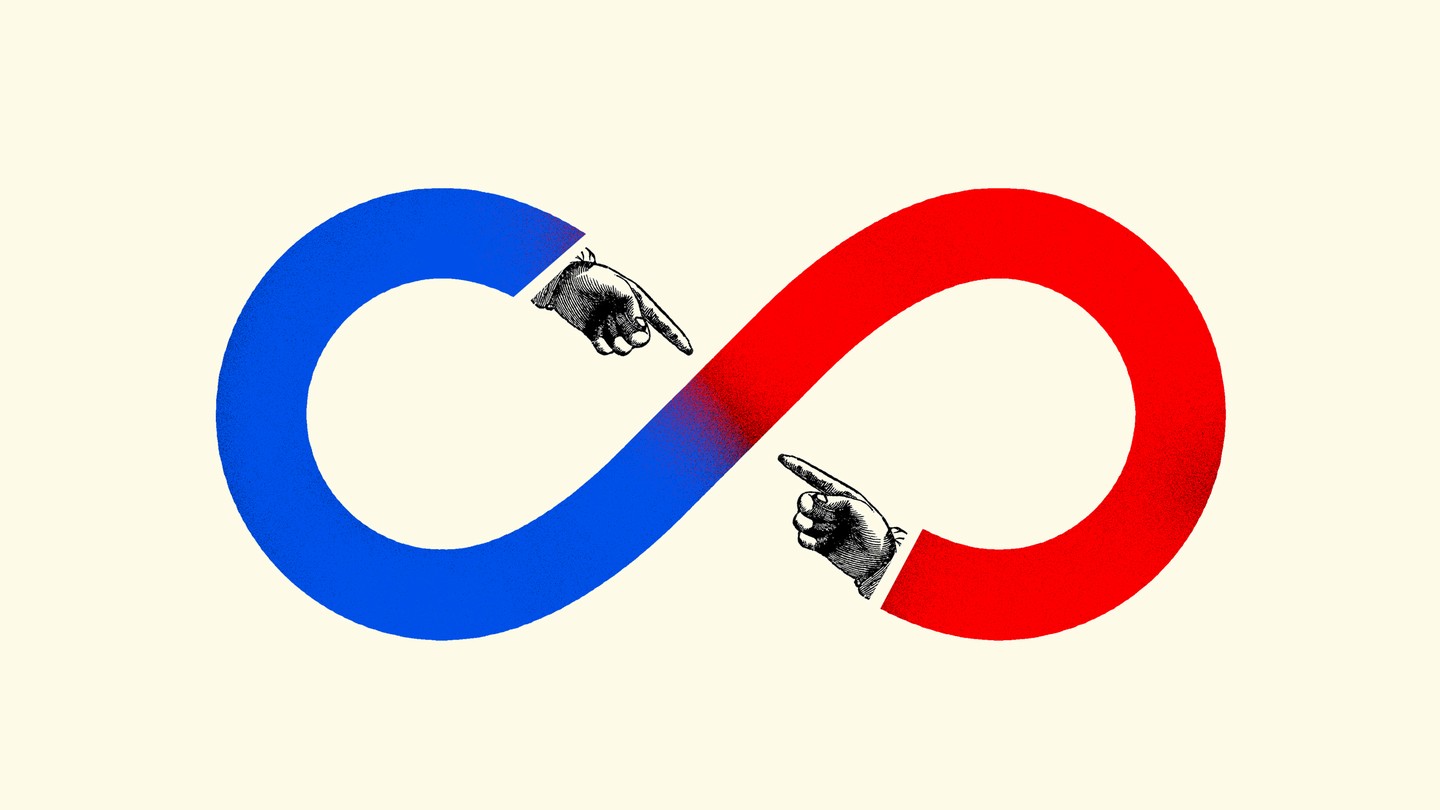

The Forever Culture War

As Republicans lurch leftward on economics and reposition themselves as the protectors of the working class, every dispute becomes a matter of identity—to the detriment of American politics.

The future of American politics is taking shape, and it is frightening. I, along with many others, thought—or at least hoped—that Joe Biden’s tenure in the White House would allow enough Americans to unspool themselves from the daily efforts of outrage and apocalyptic thinking. Biden was bland enough that politics could revert to something more measured than it had been under his predecessor, Donald Trump. This was wishful thinking.

Politics seems more existential, not less. Pundits and partisans cast everything as a culture war, even those things that have little to do with culture. Policy debates that might have otherwise been boring—over COVID-testing protocols or the cost of the Build Back Better bill, for example—have become part of an apocalyptic battle between the forces of good and evil. As the conservative writer Jack Butler characterized the growing unease: “We’re in the battle at the end of time, and the prince of darkness is already at the door, and the whole world is now a contest between activist left and activist right.”

In retrospect, it was a mistake to think that the sheer intensity of recent political debate was unusual or temporary, when it is likely to be neither. After a couple of relatively tame and boring decades, the shift made itself apparent during the Trump years. In 2012, 45 percent of Americans cited the economy as the “most important problem” facing the country. By 2017, that number had dropped to around 10 percent. The United States was far from exceptional, however. In 2018, immigration had become the top concern for voters in seven European countries, with terrorism following closely behind. The economy has since become a primary concern again, partly because of the pandemic. Yet economic debates themselves have become less polarized. There is broad agreement and even consensus across the ideological spectrum. In much of Europe, right-wing populist parties have taken a sharp left turn, positioning themselves as the true defenders of the welfare state and the working class.

The American right has lagged behind. Traditions of frontier libertarianism and trickle-down economics make old habits hard to shake. But this, too, is changing, helped along by Republicans’ growing indifference to deficit spending. Trump’s embrace of far-right nationalist tropes has obscured the Republican Party’s lurch leftward on economic issues—a shift that the writer Matthew Yglesias calls “unhinged moderation.” This impulse of right-wing identity politics and economic populism is inspiring a younger generation of conservatives on the “new right,” profiled recently by Sam Adler-Bell in The New Republic and David Brooks in The Atlantic.

Trump was radical in style and, occasionally, on policy—at least by conservative standards. He abandoned earlier Republican efforts to privatize Social Security and cut Medicare. His scrambling of traditional left-right politics gave license to young conservatives to embrace economic populism, which isn’t very conservative. The influential journal American Affairs—initially launched as a quasi-Trumpist intellectual organ—welcomes contributors from the other side and features more socialist ideas than unabashedly capitalist ones (I wrote an essay for the journal on formulating a new left-wing populism).

Various right-wing intellectuals have long fantasized about an electoral holy grail of economic populism and social conservatism. In Britain, they were known as “red Tories,” but such grand projects of realignment tended to fizzle out. They were compelling in theory but not necessarily in practice—perhaps until now. As the conservative writer and podcaster Saagar Enjeti argued in 2020: “The whole reason that the GOP has been able to even compete for so long is that despite their horrible economics, they do hold the cultural positions of so much of the American people. But they keep thinking they’re winning because of their economic policy and losing because of their cultural policy, when really it’s the opposite.”

As Democrats hemorrhage working-class support—not only among white people but also among communities of color whom the party was counting on—the new right sees an opportunity. Glenn Youngkin’s victory in the Virginia gubernatorial elections was an early test case. Youngkin, a Republican, was happy to pledge increased spending on education, for example. Few in his party seemed to mind. What mattered was culture, which is precisely what the otherwise mild-mannered former executive zeroed in on in the campaign’s final weeks. Education was the dividing line, but these weren’t your old Bush-era debates about charter schools, class size, teacher training, test scores, and budgets. Republicans may have weaponized the threat of “critical race theory,” but school closures and remote learning undoubtedly forced parents to pay closer attention to what their kids were actually learning—or not learning. The divide wasn’t about whether kids were solving their math problems; it was about values, history, and culture—the fear that the state, through its schools, was discarding the pretense of neutrality and instead promoting contested ideological propositions.

Whether this growing sense of cultural overreach by the left ultimately pushes Republicans to Ronald Reagan–style electoral victories is an interesting question. An even more interesting question is what this shift—if it becomes permanent—means for the future of American politics. And what it means is discouraging at best.

In effect, because of the GOP’s dash to the center on spending as well as on industrial and trade policy, economics has been neutralized as the country’s primary partisan cleavage. To the extent that a left-right divide is still meaningful, it matters much more on race, identity, and the nature of progress than it does on business regulation, markets, and income redistribution. Because the former are fundamentally about divergent conceptions of the good, they are less amenable to compromise, expertise, and technocratic fixes. These are questions about “who we are” rather than “what works.”

Elites in both parties enjoy a certain privilege—one appropriate to a rich, advanced democracy—that allows them to emphasize culture while deprioritizing economic well-being. Civilizational concerns gain more political resonance precisely as perceptions of civilizational decline intensify on right and left alike. But this particular kind of decadence—characterized, per The New York Times’ Ross Douthat, by reproductive sterility, economic stagnation, political sclerosis, and intellectual repetition—is an ideal foil for young conservatives cum reactionaries. It gives them something worthy of reaction. And, importantly, it doesn’t require being religious as much as it requires a recognition that religion is a vital societal good, regardless of whether it’s true.

Like Trump, the most secular president of the modern era, many of the new right’s most prominent figures are not particularly religious. Their (potential) constituency of young Republicans isn’t particularly religious either. The number of unaffiliated Republicans has tripled since 1990, much of that concentrated among the young and the relatively young.

Civilizational health, to use the term of the Claremont Institute’s Matthew Peterson, is what unites believers and nonbelievers alike. They appreciate religion’s role and utility in buttressing Western civilization, offering as it does transcendence as well as tradition. And, of course, elevating religion as the wellspring of morality is a pretty good way to own the libs, for those who place special value on that.

If this division around morality, the meaning of the American founding, and “civilization” solidifies, we should all be at least slightly worried. It would mean a multifaceted culture war for, perhaps, the rest of our lives. That’s putting it somewhat dramatically, but there is good reason to view some changes, rather than others, as extremely sticky, if not quite permanent.

There wasn’t always a left-right cleavage organized around class, redistribution, and the means of production. But it came to be, and it has persisted for a very long time. In their seminal 1967 study, Party Systems and Voter Alignments, Seymour Martin Lipset and Stein Rokkan argued that state formation, the industrial revolution, and urbanization allowed economic divides to supersede religious ones. That economic cleavages are (or were) paramount in most Western democracies, then, is no accident. Over time, the economic dimension of conflict in Western democracies became “frozen” in the form of parties that self-defined according to economic interests.

Parties play an important role too. They decide what issues to prioritize in order to distinguish themselves from the competition. As the political scientists Adam Przeworski and John Sprague note, “class is salient in any society, if, when, and only to the extent to which it is important to political parties which mobilize workers.” But neither Democrats nor Republicans are likely to become workers’ parties anytime soon. Conservatives’ rhetorical interest in the working class remains largely electoral and opportunistic. Meanwhile, the left is preoccupied with language policing, elite manners, and a kind of cultural progressivism far more popular among hypereducated white liberals than working-class Latino, Black, Asian, and Arab Americans.

Republicans and Democrats may simply converge around a diffuse and vague economic populism and call it a day. To distinguish themselves from each other in a two-party system, they will have to underscore what makes them different rather than what makes them similar. And what makes them different—unmistakably different—is culture. This isn’t just instrumental, though, a way to rally the base and mobilize turnout. If one listens to what politicians and intellectuals in these two warring tribes actually say, it seems clear enough: They believe that civilization is at stake, and who am I to not take them at their word? If the end of America as we know it is indeed looming, then the culture war is the one worth fighting—perhaps forever, if that’s what it takes.