James B. Meigs isn’t favorably impressed with Scientific American‘s recent unscientific moves. Two slices:

American journalism has never been very good at covering science. In fact, the mainstream press is generally a cheap date when it comes to stories about alternative medicine, UFO sightings, pop psychology, or various forms of junk science. For many years, that was one factor that made Scientific American’s rigorous reporting so vital. The New York Times, National Geographic, Smithsonian, and a few other mainstream publications also produced top-notch science coverage. Peer-reviewed academic journals aimed at specialists met a higher standard still. But over the past decade or so, the quality of science journalism—even at the top publications—has declined in a new and alarming way. Today’s journalistic failings don’t owe simply to lazy reporting or a weakness for sensationalism but to a sweeping and increasingly pervasive worldview.

It is hard to put a single name on this sprawling ideology. It has its roots both in radical 1960s critiques of capitalism and in the late-twentieth-century postmodern movement that sought to “problematize” notions of objective truth. Critical race theory, which sees structural racism as the grand organizing principle of our society, is one branch. Queer studies, which seeks to “deconstruct” traditional norms of family, sex, and gender, is another. Critics of this worldview sometimes call it “identity politics”; supporters prefer the term “intersectionality.” In managerial settings, the doctrine lives under the label of diversity, equity, and inclusion, or DEI: a set of policies that sound anodyne—but in practice, are anything but.

This dogma sees Western values, and the United States in particular, as uniquely pernicious forces in world history. And, as exemplified by the anticapitalist tirades of climate activist Greta Thunberg, the movement features a deep eco-pessimism buoyed only by the distant hope of a collectivist green utopia.

The DEI worldview took over our institutions slowly, then all at once. Many on the left, especially journalists, saw Donald Trump’s election in 2016 as an existential threat that necessitated dropping the guardrails of balance and objectivity. Then, in early 2020, Covid lockdowns put American society under unbearable pressure. Finally, in May 2020, George Floyd’s death under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer provided the spark. Protesters exploded onto the streets. Every institution, from coffeehouses to Fortune 500 companies, felt compelled to demonstrate its commitment to the new “antiracist” ethos. In an already polarized environment, most media outlets lunged further left. Centrists—including New York Times opinion editor James Bennet and science writer Donald G. McNeil, Jr.—were forced out, while radical progressive voices were elevated.

…..

The Covid pandemic was a crisis not just for public health but for the public’s trust in our leading institutions. From Anthony Fauci on down, key public-health officials issued unsupported policy prescriptions, fudged facts, and suppressed awkward questions about the origin of the virus. A skeptical, vigorous science press could have done a lot to keep these officials honest—and the public informed. Instead, even elite science publications mostly ran cover for the establishment consensus. For example, when Stanford’s Jay Bhattacharya and two other public-health experts proposed an alternative to lockdowns in their Great Barrington Declaration, media outlets joined in Fauci’s effort to discredit and silence them.

Adam Summers reports on the reality of minimum-wage diktats playing out in Seattle.

Art Carden celebrates the bourgeois deal.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Bjorn Lomborg warns against the radical green agenda. A slice:

Many developing nations never shared the Western elite’s obsession with reducing emissions. Life for most people on earth is still a battle against poverty, hunger and disease. Corruption, lack of jobs and poor education hamper their futures. Tackling global temperatures a century out has never ranked high among the priorities of developing countries’ voters—and without their cooperation, the project is doomed.

All the same, talk of a union renaissance might be much ado about nothing. Union membership as a share of wage and salary workers has declined steadily from 28.3 percent in 1967 to an all-time low of 10 percent in 2023. Although the absolute number of union workers has recently risen, it hasn’t kept up with the growth of the total number of American workers.

National Review‘s Dominic Pino has been following unions comprehensively. He never forgets to report both their wins and their losses. For instance, workers at a unionized Nissan facility in Somerset, New Jersey, are in the process of decertifying from the UAW. The same happened at various non-Starbucks coffee shops.

…..

By contrast, private unions have every right to exist, but this doesn’t mean they’re a good thing on net for workers. A September 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research paper looked at what a unionized workforce does to incentives and investment. While unionized plants pay higher wages and benefits than do nonunionized ones, they also “experience higher rates of closure, reduced investment, and slower employment growth.” In other words, your unionized job might pay more, as long as it doesn’t go away—and good luck finding another like it. The result holds also for partially unionized plants.

Introducing more competition to the private sector union business model could help. For that, my colleague Liya Palagashvili suggests ending the exclusive-representation clause that “provides government-granted monopoly status to a union supported by 51 percent of an employer’s workers, giving it the sole authority to negotiate. This means that if some workers want a different union—for example a newer one that might raise the bar in terms of what it can offer—they are out of luck.” Today, these workers aren’t allowed to engage in any negotiations with their employers, and they still have to pay the original union’s fees.

Adrian Wooldridge warns that “progressives forget their free-trade heritage at their own peril.”

Famines are nearly always linked to economic backwardness. Their virtual elimination globally (in peacetime) is one of the achievements of modern economic growth.

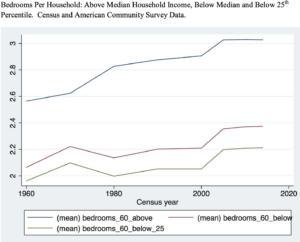

Famines are nearly always linked to economic backwardness. Their virtual elimination globally (in peacetime) is one of the achievements of modern economic growth. Consumption for below median income families has seen steady progress since 1960…. These estimates suggest that consumption is up 1.7 percent per year or 164 percent over the whole time period. These estimates of growth strike me as consistent with the significant increases in quality and quantity of goods enjoyed by Americans over the last half century. And my conclusions are consistent with the findings of

Consumption for below median income families has seen steady progress since 1960…. These estimates suggest that consumption is up 1.7 percent per year or 164 percent over the whole time period. These estimates of growth strike me as consistent with the significant increases in quality and quantity of goods enjoyed by Americans over the last half century. And my conclusions are consistent with the findings of  The conception of freedom under the law … rests on the contention that when we obey laws, in the sense of general abstract rules laid down irrespective of their application to us, we are not subject to another man’s will and are therefore free. It is because the lawgiver does not know the particular cases to which his rules will apply, and it is because the judge who applies them has no choice in drawing the conclusions that follow from the existing body of rules and the particular facts of the case, that it can be said that laws and not men rule.

The conception of freedom under the law … rests on the contention that when we obey laws, in the sense of general abstract rules laid down irrespective of their application to us, we are not subject to another man’s will and are therefore free. It is because the lawgiver does not know the particular cases to which his rules will apply, and it is because the judge who applies them has no choice in drawing the conclusions that follow from the existing body of rules and the particular facts of the case, that it can be said that laws and not men rule. It’s not so much that we “need foreign savings,” but that foreigners need, desire, demand US investments. Even when US policymakers play roulette with fiscal policy or when the world is in a seemingly chaotic state and US policymakers are exacerbating the problem, investors want dollar denominated investments in US assets. May change at some point. But for now there is a strong argument to make that foreign investment in US (not mindless consumerism) drives the trade deficit.

It’s not so much that we “need foreign savings,” but that foreigners need, desire, demand US investments. Even when US policymakers play roulette with fiscal policy or when the world is in a seemingly chaotic state and US policymakers are exacerbating the problem, investors want dollar denominated investments in US assets. May change at some point. But for now there is a strong argument to make that foreign investment in US (not mindless consumerism) drives the trade deficit. The implicit assumption that mortality rates reflect the amount or quality of medical care is seldom subjected to any empirical test in media or political discussions comparing American medical care with medical care in other countries with more comprehensive government involvement in medical care. But the relevant comparison would be between mortality rates in different countries from health problems in which medical care makes a substantial difference, even if not the only difference. This would still not be a perfect comparison, since even here other differences between the populations in the countries being compared are factors as well. But it would be a much more relevant comparison than those that are usually made by the media and politicians. When the American College of Physicians calculated the death rate for “mortality amenable to health care” the United States was in the top three countries with low death rates of this sort out of 19 countries studied.

The implicit assumption that mortality rates reflect the amount or quality of medical care is seldom subjected to any empirical test in media or political discussions comparing American medical care with medical care in other countries with more comprehensive government involvement in medical care. But the relevant comparison would be between mortality rates in different countries from health problems in which medical care makes a substantial difference, even if not the only difference. This would still not be a perfect comparison, since even here other differences between the populations in the countries being compared are factors as well. But it would be a much more relevant comparison than those that are usually made by the media and politicians. When the American College of Physicians calculated the death rate for “mortality amenable to health care” the United States was in the top three countries with low death rates of this sort out of 19 countries studied.