How Minds Change: book review

7 ideas to take away

This is a book review of How Minds Change, The Surprising Science of Belief, Opinion, and Persuasion, a new book by David McRaney.

How Minds Change offers useful ideas for marketers, communicators, and leaders about communications and persuasion. Among them are these 7 takeaways:

- Disagreement is a natural human condition that enabled humans to survive.

- Don’t ask who’s right. Ask, “Why do we see things differently?”

- Facts alone seldom change people’s minds.

- People are biased toward their own opinions, and they off-load cognitive labor through a group deliberation process that may or may not lead to a consensus.

- To change people’s minds, gain their trust with radical hospitality, a selfless concern and energetic friendliness that emphasizes listening and asking questions rather than arguing.

- Avoid debates since they have winners and losers. People hate to lose.

- In the end, all persuasion is self-persuasion.

Why do people disagree so often?

“Why do we argue? What purpose does it serve? Is all this bickering helping or hurting us?”

These key questions are asked and answered in How Minds Change by David McRaney.

As a species, humans “evolved to reach consensus,” notes cognitive scientist Hugo Mercier. Through human history, tribes that worked their way through disagreements and reached consensus were able to out-compete tribes that couldn’t.

So disagreeing is not a bug; it’s a feature of human brains that serves a specific purpose.

As social primates, we “gather information in a biased manner for the purpose of arguing for our individual perspectives, in a pooled information environment, within a group that deliberates on shared plans of action toward collective goals. We are lazy because we expect to off-load cognitive labor to a group deliberation process … before planning our shared decision on how to proceed based on shared motivations.”

In a community where it’s safe for each individual to state their case, the ensuing conversation harnesses the cognitive power of the whole tribe to do hard thinking and come up with their story about what’s going on.

Today people disagree so much that pundits call this the “Post-Truth World.”

But that’s a misnomer, because it imagines that humans used to live in a paradise of shared truths – which never happened. Instead, we live in a “Post-Trust World.”

Sometimes it takes decades to change minds

People change their minds on major issues slowly. It may take a whole generation, or even longer.

For example, dueling with guns was once a respectable practice. When newspapers criticized dueling as a legal form of murder, more people took up dueling. Once commoners started to duel, aristocrats dropped it within one generation.

“Every era, every culture, believed it knew the truth, until it realized it didn’t; then when the truth changed, the culture changed with it.”

Similarly, after the new idea of a designated driver appeared in 1988, alcohol-related auto fatalities dropped by 24%.

Certainty isn’t rational, it’s emotional

Why do people change their minds so slowly, or so quickly? “The speed of change is inversely proportionate to the strength of our certainty,” writes McRaney. Certainty is not a rational process – instead it’s a feeling that fits somewhere between an emotion and a mood.

The “ability to change our minds, update our assumptions, and entertain other points of view is one of our greatest strengths … to leverage that strength, we must avoid debates and start having conversations. Debates have winners and losers, and no one wants to be a loser,” McRaney says.

The right kinds of conversations employ radical hospitality, a selfless concern and energetic friendliness that emphasizes listening and asking questions rather than arguing. Listening attentively and asking questions helps people recognize that their own ideas may consist of received wisdom, rather than their own original thinking.

At their best, good conversations encourage people to stop and think, to process things they never thought about before, and to start to see things differently.

McRaney shares research on multiple techniques that trigger the right kinds of face-to-face conversations – including deep canvassing, smart politics, motivational interviewing, and street epistemology.

For example, in a study by David Brockman and Josh Kalla, deep canvassing proved 102 times more effective than traditional canvassing, TV, radio, direct mail and phone banking combined. Here’s a Rolling Stone article on the deep canvassing as a political technique.

Face to face communications are crucial since they overpower all other media.

Do facts change people’s minds?

Can facts alone make everybody see things the same way? No.

When faced with facts they can’t explain, people only dig in deeper to the position they hold. Until a person gathers enough evidence to feel at least 30% uncertain, they’re highly unlikely to change their minds due to a newly presented fact.

Feeling certain is an emotional response.

People often try to change someone else’s mind by applying a concept called the information deficit model. People imagine that, if only the person whose mind they’re trying to change knew all the facts, their minds would change.

But that’s simply not true. People hold certain ideas because their ideas give them identity, and “social death is more frightening than physical death.”

That’s why truth is tribal. Today, people belong to many different tribes. That lowers the social cost of changing your mind, compared with past centuries when people could belong to only one tribe.

To relinquish an idea often leads to becoming an outcast from a community, or even a scapegoat. That’s why people fight to the death about ideas that threaten their sense of belonging to a tribe.

It’s human nature: people cling tightly to their own beliefs while savaging others’ beliefs.

Perceptions do not equal reality

People are used to agreeing on the facts but reaching different conclusions about what they mean.

But sometimes, we can’t even agree about whether our own perceptions represent reality.

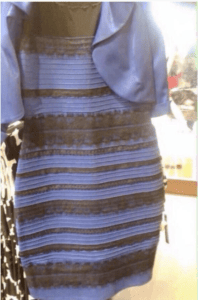

For example, you may recall The Dress meme from 2015. When people look at this image, some see a black and blue dress, others see a white and gold dress. What do you see?

Since the Dress image is ambiguous, our minds see what they expected to see. But there are 30 steps in the human visual process before an image reaches our consciousness – steps that we’re generally unaware of.

When an image is ambiguous, different people’s brains disambiguate it differently. People who’ve mostly been exposed mostly to indoor lights (predominantly yellow) see a black and blue dress. People who’ve mostly been exposed to natural light see a white and gold dress.

How can people who saw the same image come away with different impressions of the Dress’ color? Brains automatically disambiguate ambiguous images.

“When truth is uncertain, our brains resolve that uncertainty by creating the most likely reality they can imagine based on our prior experiences.”

When people disagree about the color of the Dress or other topics, “In both groups, people then begin searching for reasons why so many people in other groups can’t see the truth … without entertaining the possibility they aren’t seeing the truth themselves.”

Instead of asking who’s right, ask, “Why do we see things differently?” That question can open the door to valuable collaboration.

One key to stronger persuasion is telling stories to trigger narrative transport. Or, invite people to tell you their story. “People don’t rebut stories because they feel swept up” in a story. Stories are one key element of a great Message Map.

McRaney defines persuasion variously as:

- A force that affects our feeling of certainty.

- The act of changing a mind by voluntary acceptance, without coercion.

- Encouraging others to realize change is possible.

In the end, he says, all persuasion is self-persuasion.

To successfully persuade anyone, share your intentions up front – or else people will make assumptions about your intentions. If people believe that you think them gullible, stupid or deluded, they’ll resist your attempts at persuasion even more.

“Persistence and luck change minds, not genius. The ideas that change the world are the ones in the heads of people who refuse to give up,” McRaney writes.