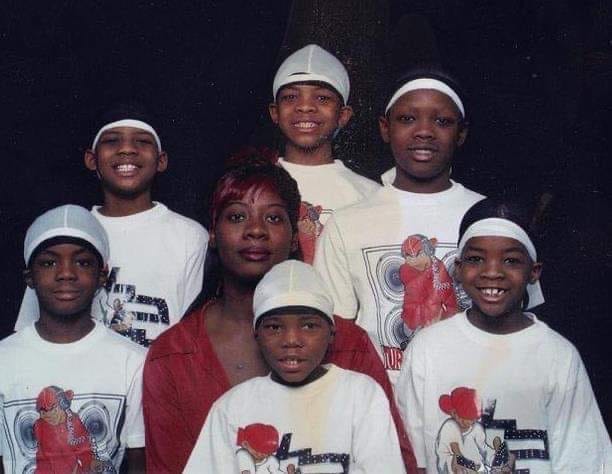

Photo of Mozell Jones-Grisham by MICHAEL HENSDILL for USA TODAY

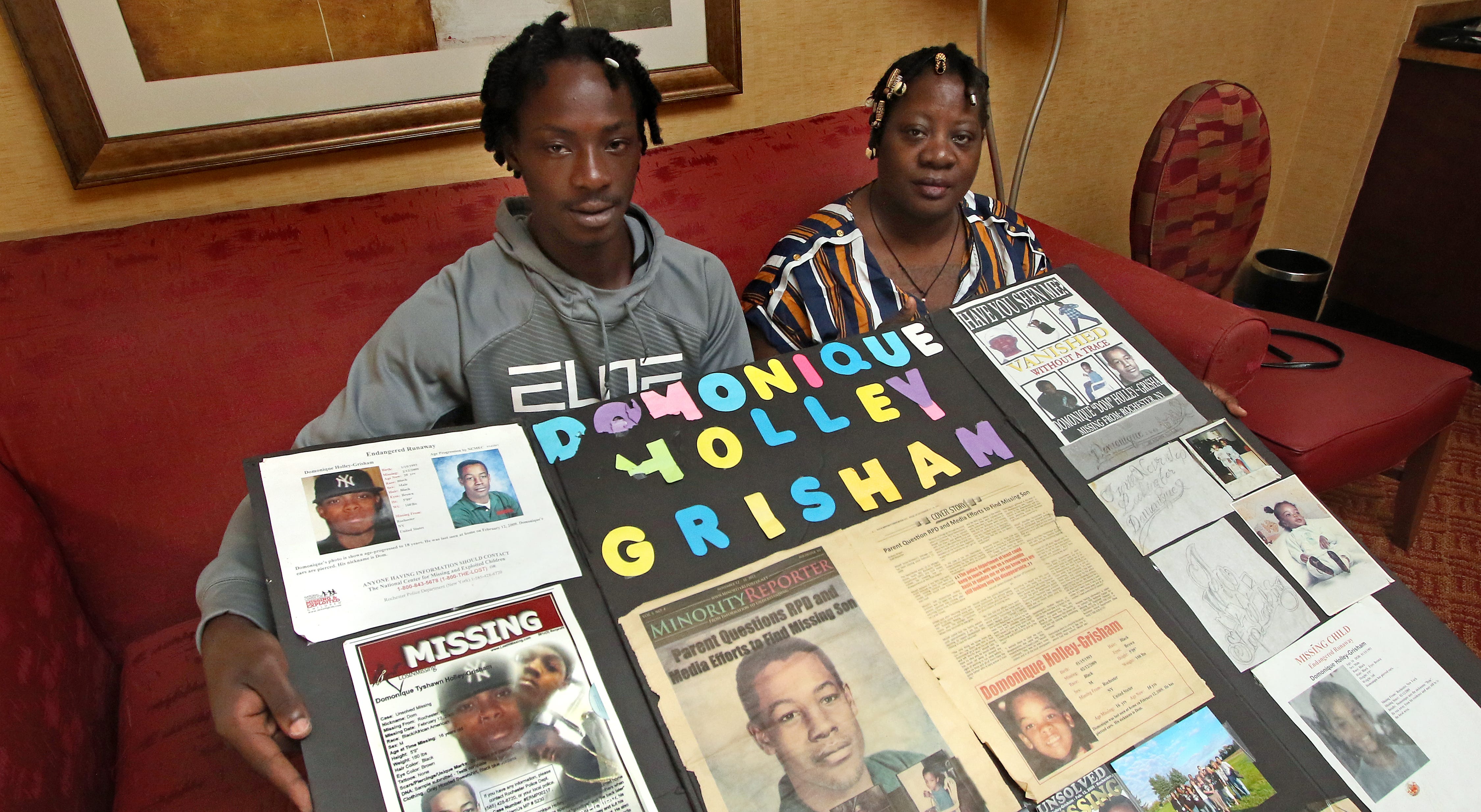

Photo of Mozell Jones-Grisham by MICHAEL HENSDILL for USA TODAY

Antonio Holley-Grisham remembers Feb. 12, 2009, as well as any 12-year-old could have.

His big brother, Domonique, made bacon, eggs and pancakes for breakfast, then left for a floor hockey tournament. When he got back, the two of them played a video game. Antonio doesn’t recall exactly what they argued about, but he says Domonique broke the game. A short time later, Domonique, 16, got a phone call and walked out of the house.

Antonio hasn’t seen his brother since. Neither has anyone else in the family.

“I was beating myself up, like I’m the reason why he left,” said Antonio, now 26. “I still get depressed over it. ... I sit here and race my mind every day, wondering where he’s at.”

Antonio’s darkest fear is that one day his brother will be found dead.

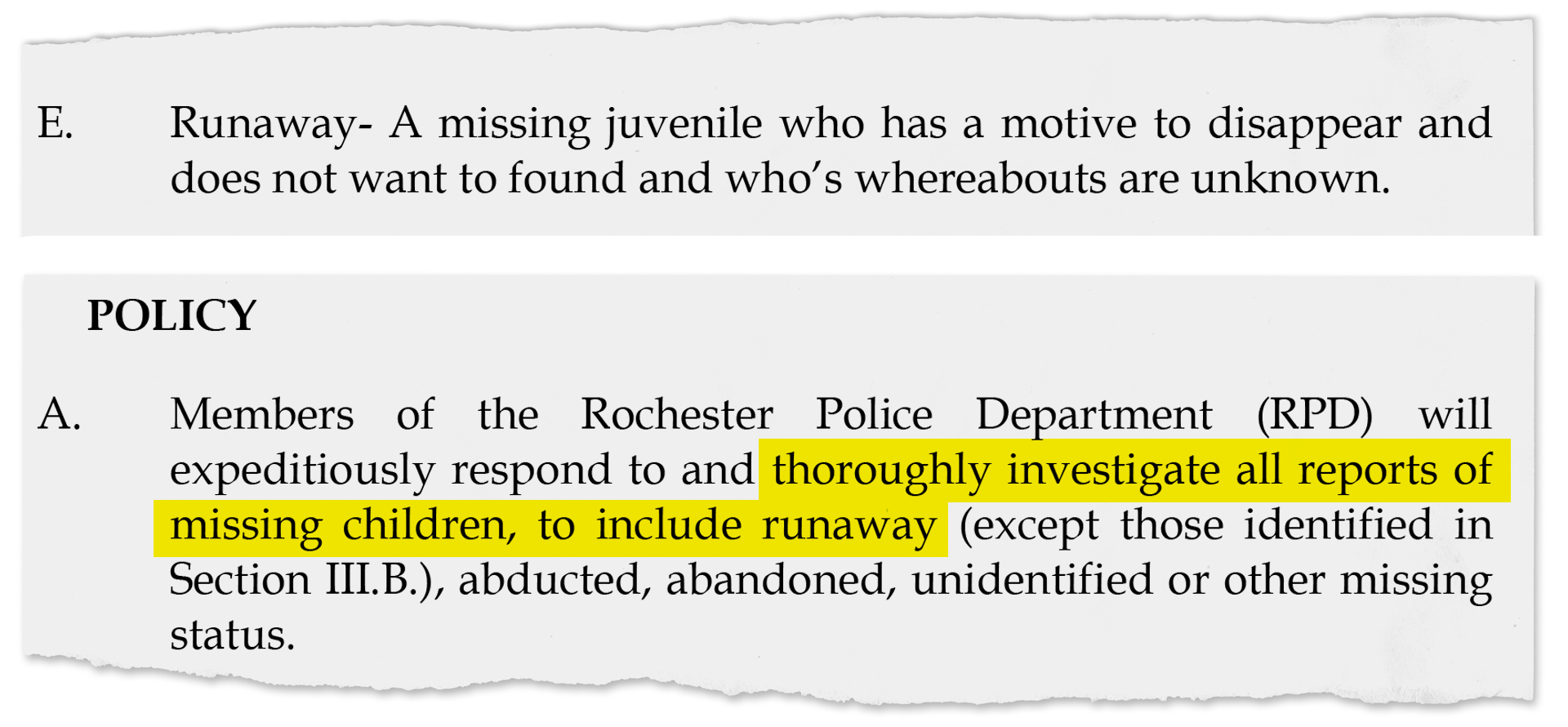

Because Domonique left of his own accord, he was considered a runaway by the police in Rochester, New York, where he lived.

Around the country, classification as a runaway often means officers put less effort into looking for a missing child, according to a USA TODAY review of more than 50 police procedural manuals. Under federal rules, runaways also are disqualified from Amber Alerts – notifications to the media and on billboards and cellphones that draw urgent and widespread attention to missing children.

In 2021, 335,000 reports of missing children were sent to the FBI, down from 365,000 the year before. About 90% of them were found. By some estimates, 100,000 more each year are never reported to the FBI because they are found so quickly. Of those not located within six months, a disproportionate number are Black, like Domonique.

USA TODAY’s review of standard operating procedures for law enforcement agencies across the nation is part of an ongoing examination of disparities in cases of missing children. Other stories have uncovered age cutoffs that allow police to avoid giving full attention to children as young as 10 and exposed Amber Alert rules so stringent that most missing kids don’t get them.

A request for the Rochester Police Department's records in Domonique's case is still pending after 10 months; an attorney for the city told USA TODAY the documents will not be released because the investigation is ongoing. But investigator Frank Camp, the department spokesman, acknowledged that no one is assigned to the case.

In an email, Camp said the following steps were taken in response to the original missing person’s report about Domonique: “A photo was obtained, a description acquired, a supervisor notified, the officer spoke with relatives (mother and a sibling) and an attempt was made to contact another relative, who was learned to be out looking for the missing person.”

The police officer sent out a broadcast to all officers asking them to be on the lookout for Domonique. The first investigator assigned to the case filed a missing persons teletype, which is a notification to the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services and the FBI’s National Crime Information Center. Rochester police contacted the resource officer at Domonique’s school and spoke with his girlfriend, Camp said.

Rochester police rules at the time dictated that the department “thoroughly investigate” all reports of missing children, including runaways, unless they left group homes. Such investigations also should have included searching the neighborhood and contacting additional units within the department or neighboring agencies, the rules say. But a supervisor was not required to come to the scene and ensure those things were done unless a child vanished under “exigent circumstances.”

Such circumstances were defined as those that “would put a person in imminent danger of serious bodily harm or death, either at the hands of another or due to a proven mental or physical disability or the age of the person requires immediate attention,” according to a general order in effect at the time in Rochester, the Monroe County seat.

The investigator who took over the case in 2012, John Brennan, said Domonique’s social media postings indicated he could have been at risk for suicide, and his family said he struggled with depression and anger. Nonetheless, the first officer on the case decided his disappearance didn’t meet the criteria for exigent circumstances.

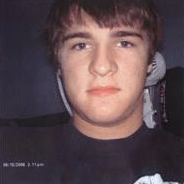

Just over a year before Domonique vanished, one of the local agencies that often collaborates with Rochester police, the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office, conducted an extensive search for another missing teen.

Like Domonique, Andrew Dezio, 15, left home after a family argument. Unlike Domonique, Andrew was white.

Members of the sheriff’s department, which serves Andrew’s hometown of Penfield, New York, combed the area on horseback and all-terrain vehicles, deployed scent dogs and called in the state police to search from the air by helicopter, according to news reports at the time. Authorities also tracked Andrew's cellphone, which ultimately led them to his remains. The Monroe County Medical Examiner ruled his death a suicide.

Rochester police said race didn’t play a role in their investigation of Domonique’s disappearance. His mother, Mozell Jones-Grisham, feels certain they would have taken it more seriously if he were white.

“They just labeled him as a runaway, as, ‘Oh, he’s all right’ or ‘He’ll be back’ or ‘He’s just blowing off steam,’” she said. “When as a mother, in my gut, I think something happened to my son.”

Brennan acknowledged that in the early days, police didn’t believe Domonique was in danger. Postings on social media showed he was sad and angry over a breakup, Brennan told USA TODAY. Domonique also called his mother during the argument with Antonio, Brennan said, and may have been upset further by the conversation.

“I think a lot of people were thinking, ‘A 16-year-old guy, mad at his mother, he just left the house and he’s going to come back,’” said Brennan, who retired in 2021.

How long do police look for runaways?

Of the 55 law enforcement agencies whose policy manuals were reviewed by USA TODAY, more than 40% allow police to exert less effort to find runaways than other missing kids.

In Nashville, Tennessee, for example, police must search for missing children for at least three hours, according to the department manual. The document lists an exception for runaways who are not disabled or believed to be endangered: “In those incidents where it can be reasonably determined that a missing juvenile, age twelve or above, has left voluntarily (runaway) … a search can be terminated prior to the three hours.”

Such practices have led advocates to push for an end to the “runaway” label.

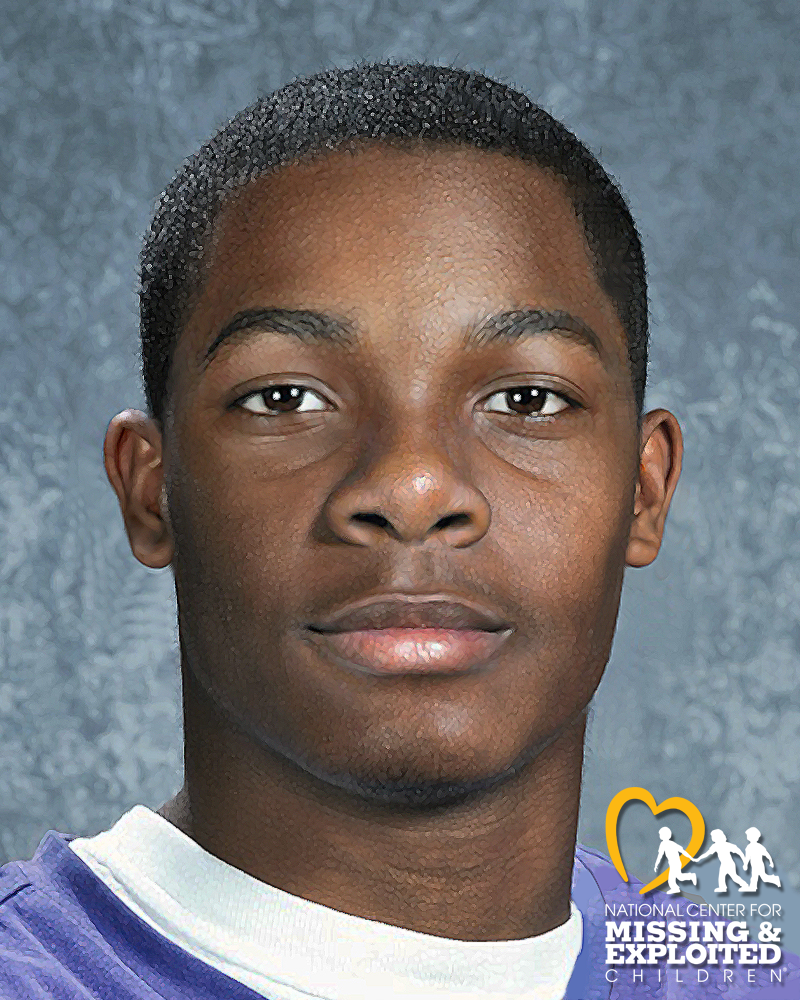

In 2012, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children redesigned its posters to remove the classifications of “runaway” and “family abduction.” The change was made because of the judgments people make when they hear those words, according to Angeline Hartmann, the center’s media director.

“Was that child actually lured away? Is that child going to meet somebody and was meant to come back 10 minutes later?” she asked. “There are lots of things that happen when a child is supposedly under the term ‘runaway.’”

The National Network for Youth, which lobbies lawmakers to prevent and end youth homelessness, no longer refers to the children it serves as runaways, Executive Director Darla Bardine said.

“There’s just such a negative public perception around runaways: that they just don’t want to follow the rules, they just want to go party and drink, as opposed to leaving a family crisis or abuse,” she said. “It’s a little bit of both. … They’re going to make bad choices, but it doesn’t mean they’re a bad person.”

Some police departments have followed suit.

In Milwaukee, Wis., police no longer use “runaway” because of the stigma attached to it, which is associated with attention-seeking and problematic behavior, according to Sgt. Efrain Cornejo. Instead, the department uses the term “habitually missing.”

“A child may be missing – and not on their own terms – but because they were labeled a runaway people may not take it as seriously,” he said.

In Washington, D.C., Chanel Dickerson managed missing persons investigations as commander of the unit from late 2016 through spring 2018 and later as assistant chief. She instructed officers to treat all missing children the same regardless of race or whether they were believed to have left home voluntarily. Dickerson, a Black D.C. native, told USA TODAY that when she was young, she observed injustices she blames on officers labeling children runaways.

Under Dickerson's leadership, the police department produced flyers and notified the media about all missing children.

That change is not reflected in the department’s online policy manual, however. It gives the watch commander the final word on whether a missing person should be classified as critical. Flyers are prepared only for those who receive that label. After hours, the public information officer is to be paged “if media consideration is necessary.”

The manual “definitely deserved a high-level amendment,” said Dickerson, who has retired from the police department and now is a consultant helping girls in foster care. Otherwise, a new commanding officer could unilaterally reverse the changes she made.

“You should be able to look at the police department's guidelines to know what to expect when you call to report someone missing,” she said.

Racism and slurs at school

To those close to Domonique, it didn’t make sense that he would have run away the day he disappeared – or that he would have stayed out of touch forever. But his mom and his next-door neighbor, Jeremy George, said a couple of years earlier might have been a different story.

At that time, Domonique and one of his five brothers, Jessie, had moved in with family friends in the suburbs after their mother suffered a stroke. They stayed there once she recovered because she thought they would be more likely to get into college if they avoided Rochester’s school district.

It was a difficult environment for Jessie and Domonique. Students at the virtually all-white suburban school bullied the brothers and used racial slurs against them, including the N-word, Jones-Grisham said.

Domonique and Jessie would say: “We’re going to run away. ... We’re going to meet up somewhere, and we’re going to live together,” she recalled.

Instead, Jessie joined the Marines and Domonique returned to his mother’s home, transferring to East High School in Rochester. Things seemed to be looking up.

On the day he was last seen, Domonique’s floor hockey team won its tournament, and he was named MVP, Jones-Grisham said. She decided to throw him a party to celebrate the victory and, belatedly, his 16th birthday, which had been about a month earlier.

Jones-Grisham clearly remembers the last time she saw her son: As she headed out to pick up a cake and party supplies, he was burning CDs to play that evening.

“He was just happy ... to get ready for his party,” she said.

A short time after the brothers argued about the video game, Domonique spoke with someone on the phone and left the house, according to Antonio and George, the neighbor.

The time for the party came and went. No Domonique. When he still hadn’t returned several hours later, his mother called the police.

In many cities, being a runaway is a crime

Even if the police were to find Domonique, they couldn’t force him to go home, Brennan said. Running away is not a crime in New York.

In at least 10 other jurisdictions, however, it is considered a low-level crime – known as a status offense – that can be listed on a juvenile’s record, like truancy or a curfew violation, according to USA TODAY’s review of police policy manuals.

Honolulu stood out: It requires all runaways to be arrested when they are found.

Several other departments require an arrest when runaways are found in a different jurisdiction from where they were reported missing, allowing authorities to keep track of them while they gather information. At least two agencies, the Pennsylvania State Police and the Cobb County Police Department in Georgia, let officers decide whether to make an arrest.

Michelle Yu, a spokesperson for the Honolulu Police Department, said the agency’s arrest policy was intended to bridge a gap in services. The state can’t refer young people directly to social service programs, she said. Instead, they must be evaluated to determine what help they need. In Honolulu, those evaluations are done at a privately contracted assessment center.

“When the assessment center was created, it was decided that the youths should be arrested so that they could be legally taken into custody for transport to the center,” Yu said in an email. “This offers legal protection in case of injury. An arrest also puts the youth under the jurisdiction of the family courts.”

Children who leave home need help, not punishment, said Bardine, the youth advocate.

“We know that most runaways are running away from domestic violence, mentally ill parents, substance abusing parents, or sexual abuse,” she said. “It’s not a fight about broccoli or ‘You didn’t buy me an iPad.’ There’s conflict or crisis in this family.”

In recent years, advocates and law enforcement officers have begun to realize that “home isn’t always safe,” said Susan Frankel, CEO of the National Runaway Safeline, a Chicago-based nonprofit for young people in crisis.

“Some of this is caught up in really understanding who is the victim and what the circumstances are,” Frankel said. “As a society in general, I don’t think we’re particularly forgiving or kind, or like the high-school-aged group much.”

Dallas takes the opposite approach of many police departments when it comes to runaways: Children 10 to 17 who have left home three times in six months are immediately assigned to the high-risk victims and trafficking team and considered a priority. Once children are found, they are not arrested – even if they have been engaged in prostitution.

That’s because frequent runaways and those with a history of sexual abuse are prime targets for human traffickers, according to Byron Fassett, a retired sergeant who created the Dallas high-risk unit – the first of its kind in the nation – in 2003.

“There is almost always trauma,” he said.

Detectives in the high-risk squad partner with specially trained interviewers at the Dallas Children’s Advocacy Center, who figure out what the youths have been through while they were on the streets. Then, caseworkers from Traffick911, a nonprofit, build relationships with each child, empowering them to get the help they need.

In Milwaukee, the police department recently started a new program to track young people who repeatedly leave home and connect them and their parents with a county-run mentoring program for high-risk youth and wraparound family services, Cornejo said.

In addition, officers direct teens who repeatedly leave home to two drop-in youth shelters where they can find safe temporary housing, said Officer Keyona Vines, who investigates missing persons cases.

“They might have gotten into an argument with their mom and they need a break,” she said. “We can’t be there 24 hours, so they can go to a safe place.”

Today, Rochester police refer chronic runaways to the city’s Persons in Crisis Team, which connects them and their families to social services organizations. A precursor to that program existed in 2009, according to Camp, the department spokesman.

If Domonique’s experiences at the suburban school traumatized him to the point of wanting to run away or harm himself, he never told his mother. Jones-Grisham said Jessie didn’t share what they had been through until after Domonique disappeared.

“I thought I was doing something good by sending them to an out-of-town school,” she said. “But it was really hurting them.”

Reporting a missing person

A lack of trust and poor communication have marred the relationship between Domonique’s family and the Rochester police. That disconnect and the passage of time make it impossible to know for sure what really happened the day he disappeared and how hard police worked to find him.

Jones-Grisham said that when she first tried to report her son missing, she was told she had to wait 24 hours. She then contacted her uncle, Henry Rouse, a sheriff’s deputy, who called in a favor, she said. A police officer arrived at her house shortly before 1:30 a.m., according to the initial missing person’s report, which Jones-Grisham has kept in storage since 2009. It does not list the time of her original call.

Rouse has since died. Camp said that as far as he knows, there has never been a waiting period to report someone missing in Rochester. The department rules in effect in 2009, the year Domonique disappeared, state that police should respond “expeditiously” to reports of missing children and runaways and should forward the information to the state “without delay.” By 2015, the rules had been updated to specifically state that there is no waiting period for reporting a missing person.

Camp allowed that someone in the 911 emergency communications department, which is separate from the police department, could have given Jones-Grisham incorrect information about a waiting period.

The next-door neighbor, George, told USA TODAY police didn’t question him until three or four years later even though he was at Domonique’s house the day he was last seen and watched him walk out the door.

The police report does not contain George’s name or his contact information. The officer who responded to the original report, Gregory Bello, declined to comment and referred questions to Camp, who did not answer questions regarding George.

Jones-Grisham said there was a surveillance camera on the corner where her family lived, which the police had set up to keep tabs on drug dealers in the area. She’s sure, she said, because she recognized her front door in surveillance video aired on a television report about a drug bust. When she asked the police to check it for clues about Domonique, Jones-Grisham said, they told her the footage could only be used for narcotics investigations.

Brennan said he investigated that allegation after he was assigned to the case in 2013 and determined there was no camera in the neighborhood in 2009. Even if there had been, he didn’t think it would have been useful.

“People are like: ‘Well, what if a serial killer picked him up in a car and took him away?’ Is that possible? Sure, it’s possible, but a 16-year-old boy? He wasn’t a weakling. He wasn’t somebody that was going to go easy,” Brennan said, noting that Domonique was tall and athletic.

The police also never figured out who Domonique was talking to before he left the house. Jones-Grisham told USA TODAY he was using a prepaid cellphone, which would have been more difficult to track than one with a contract. Still, officers could have gotten a subpoena to see who was on the other end of the call, said Susan Landau, a professor of cybersecurity and policy at Tufts University. They also could have determined which towers routed the call for clues about Domonique’s location.

But Brennan said Domonique’s mother and his ex-girlfriend told him in 2012 that the teen didn’t have a cellphone. When Domonique called his mother about the argument with his brother, Brennan said, he used a landline.

Brennan said the case has stuck with him although he has retired. In most of the cases he has investigated, he knows what happened, he said, even if he can’t prove it in court. But the streets were silent when it came to Domonique.

“I just don’t believe he’s alive, unfortunately,” Brennan said. “And I don’t know if it’s foul play or suicide.”

'Missing for 14 years'

Often, when children go missing, strangers reach out to their parents via phone, email or social media. Some think they’ve seen the child but are mistaken. Others are malicious, blaming the parents or hurling racially charged insults.

Jones-Grisham is no exception. She has received dozens of tips about Domonique, raising her hopes only to have them dashed again.

A woman claimed she had given birth to Domonique’s baby, but she didn’t show up when Jones-Grisham arranged to meet her. One man said Domonique’s body would be found in the fast-flowing Genesee River; another was certain he had seen Domonique at a gas station in Clarence, New York. Jessie drove more than 50 miles to look at the surveillance video, but the man in it wasn't his brother.

Camp said the department would never ignore a credible piece of information. “Should a lead come in, it is then followed up,” he said.

“The case has also been periodically revisited since 2009, and the Rochester police have utilized follow-up investigative techniques such as review of social media, K-9 search attempts, participation in a documentary, podcast and newspaper interviews,” he said. “As far as the Rochester Police Department is concerned, this case, although cold, will never be officially closed until hopefully it can be solved and bring some measure of comfort to the family of Domonique.”

Jones-Grisham has accepted that after 14 years, her son is probably dead. She calls the Monroe County medical examiner’s office every once in a while to see if any unidentified bodies match Domonique’s description. Her family has submitted DNA to databases that could help identify his remains if they’re found.

“I’m just looking for closure as to where my baby is,” she said.

For Antonio, the little brother who looked up to Domonique, that thought is too much to bear.

“He’s missing, but he’s not dead. He's not,” Antonio said. “He can’t be.”

Contributing: Ashley Luthern, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel