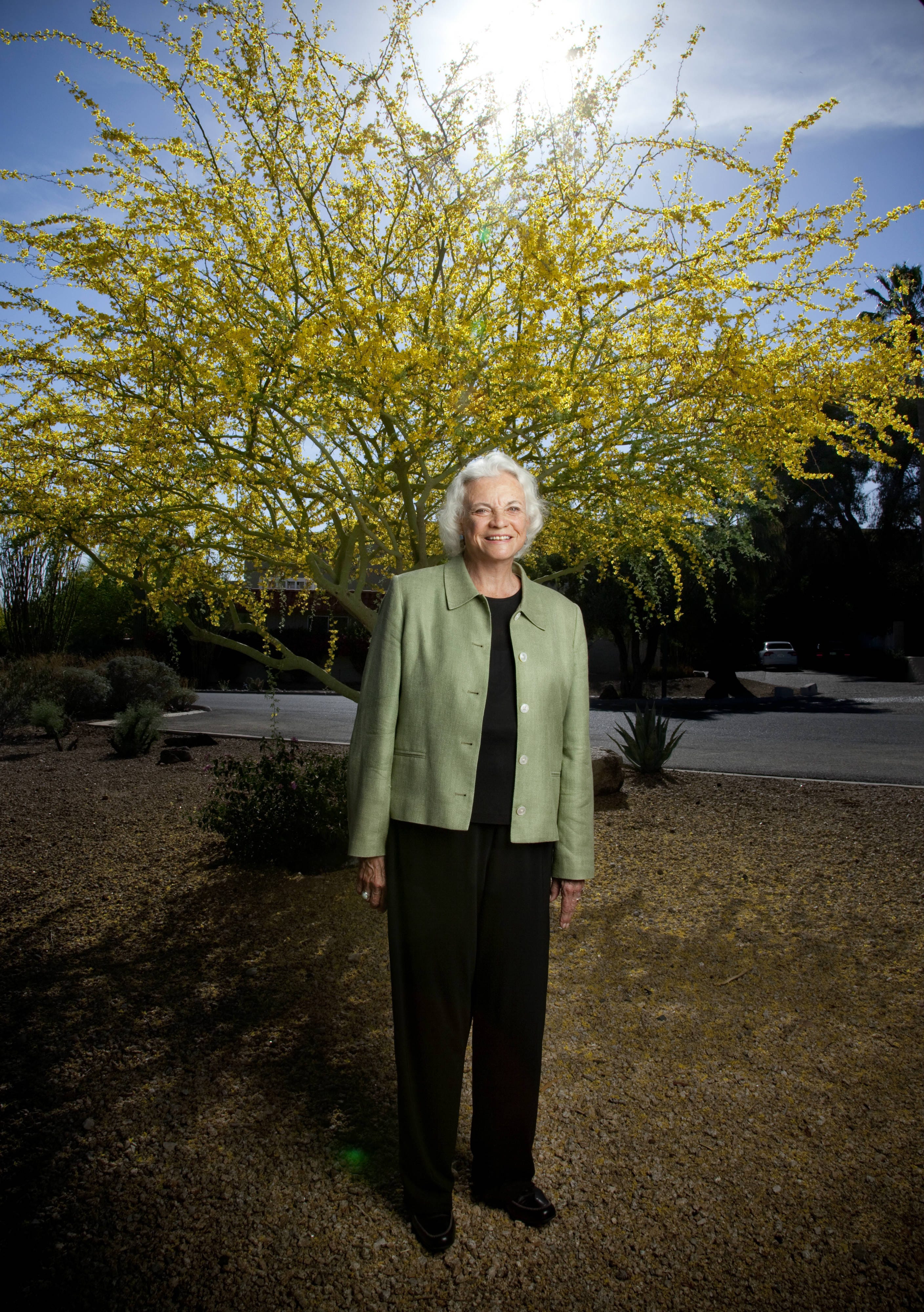

Tim Dillon, USA TODAY

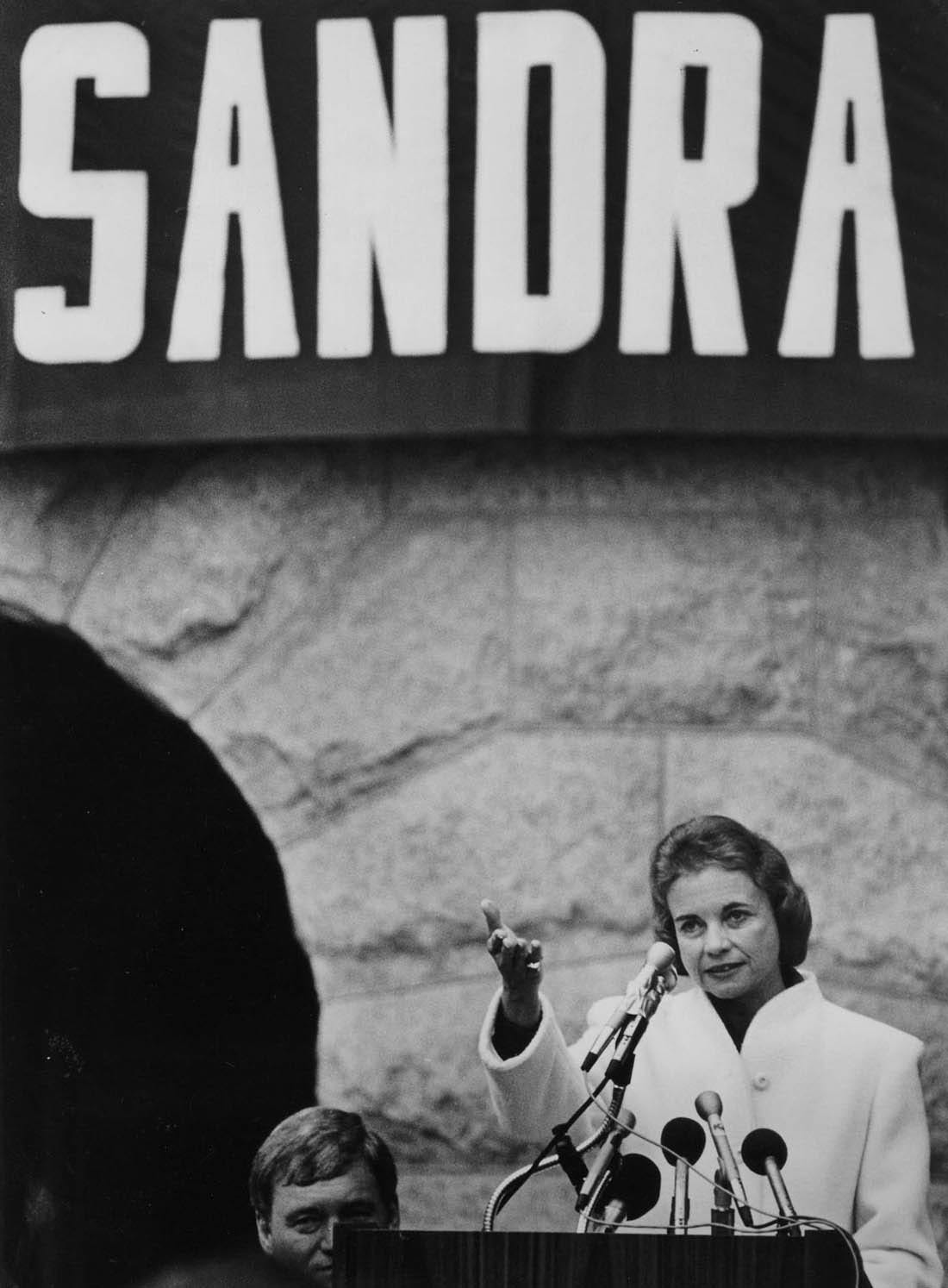

Tim Dillon, USA TODAY

Sandra Day O'Connor is one of USA TODAY’s Women of the Year, a recognition of women who have made a significant impact in their communities and across the country. Meet this year’s honorees at womenoftheyear.usatoday.com.

Sandra Day O'Connor is out of the public eye. At 93, she has lived a private life in Arizona since sharing she had dementia in 2018.

But the work of O'Connor, the first woman on the U.S. Supreme Court, was front and center in 2022.

She was the author, with Justices Anthony Kennedy and David Souter, of the court's opinion in the 1992 case Planned Parenthood v. Casey. That ruling upheld the abortion rights granted by Roe v. Wade and held that states could impose restrictions on abortion as long as they didn’t pose an “undue burden."

Her opinion also cited “stare decisis,” the principle of adhering to precedent, in upholding Roe.

In overturning the right to an abortion in June, the court reversed course and discarded precedent, renouncing the rulings of both Roe and Casey. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, Justice Samuel Alito wrote, "Precedents should be respected, but sometimes the Court errs, and occasionally the Court issues an important decision that is egregiously wrong. When that happens, stare decisis is not a straitjacket."

O'Connor's oldest son, Scott, says Alito is the one who got it wrong.

"I don't buy the rationale in Dobbs," he said. "I understand that the makeup of the court has changed, has got a more conservative majority, but I was disappointed in the quality of the rationale for the decision."

He says precedent should matter.

"It's heartbreaking to see Mom's most famous cases be reversed by her immediate successor that filled her vacancy," he said. "That's rough."

He saw the stress the Casey decision put on his mom.

"She got more mail on the abortion cases than any other cases she ever had," he said. "And on that big one, there are three co-authors of the main opinion, not one. And that was Mom trying not to be the sole focus of all the hate, and she was able to get Souter and Kennedy to join her in the opinion, so that they could distribute the burden a little bit."

O'Connor was known for being a centrist on the court. She was often a swing vote, bridging the gap between the court's conservatives and liberals. In 2000, O’Connor cast the decisive vote in a case among the court's most controversial and one that would change history — Bush v. Gore. O'Connor herself said the case that allowed George W. Bush to claim the presidency "stirred up the public" and "gave the court a less-than perfect reputation."

"Obviously the court did reach a decision and thought it had to reach a decision," she told the Chicago Tribune editorial board in 2013. "It turned out the election authorities in Florida hadn't done a real good job there and kind of messed it up. And probably the Supreme Court added to the problem at the end of the day."

What would she wish for the court now?

"That everybody was more collegial and less partisan-driven in the legal analysis in the opinions, and that there was more of a center of the court," Scott said. "I'm sure that's what she'd be thinking."

O'Connor was also passionate about teaching kids civics. She has said she's just as proud of this work as she is of her work on the bench.

Scott said the work started after the Terri Schiavo case erupted in Florida. Schiavo collapsed in 1990 from full cardiac arrest that deprived her brain of oxygen. Multiple doctors confirmed she was in a persistent vegetative state. Her husband and parents disagreed over ending life support and ended up in court, which sided with the husband and said her feeding tube could be removed. But then-Gov. Jeb Bush signed "Terri's Law," allowing it to be reinserted. Schiavo died in 2005 after a final court ruling to remove the tube.

"Mom was afraid that cases like that would motivate politicians to take the judging away from the judges, and that's not how our system is designed," Scott said. "We have this fantastic Constitution with three co-equal branches, and she saw a threat to the co-equal third branch of the judiciary that the politicians were going to try, when there was a decision they didn't like, that the politicians would want to grab turf from the judges.

"She saw that as a real threat to our system."

O'Connor started a website to teach young people about the court system but soon realized they needed to know far more about our democracy.

"That was the eureka moment," Scott said. His mother created the nonpartisan iCivics as a way to teach kids about self-government. "And she's had good people working there ever since that have grown it from the little humble beginnings to this school year, they could potentially hit 10 million students. Isn't that just amazing?"

This month, the Sandra Day O’Connor Institute for American Democracy launched a new website, Civics for Life, to educate all ages about civic engagement.

On the bench and with her civics education, O'Connor wanted to reinforce that politicians should not interfere in the courts.

"The court is still doing its job," Scott said. "The run she had at one point, the court went 11 or 12 years without a change, and that group really worked well together. Sure, there were some snarky footnotes along the way, but it was a really good group that stayed together for 12 years, and it's evolved quite a bit since then. And right now it's a pretty divided court, and so I think she'd just be sad to see it this divided."

He wants his mom to be remembered as someone who represented the mainstream.

"She wasn't an extremist at all," he said. "And I think at the top, top levels of our government, I think you need people that are grounded and centered and are in touch with sort of mainstream America so that we have less screaming and shouting and carrying on and trying to drive it from the fringe. She represented dead center mainstream, what it was to be American. She got it."

In October 2009, Carroll interviewed O'Connor along with Ruth McGregor, O'Connor's former clerk and retired Arizona Supreme Court chief justice. The interview is reprinted here, edited for length and clarity.

In your early childhood, back on the Lazy B Ranch, your parents had great expectations for you and your brother and your sister. You are now known for having a no-excuses work ethic. Can you talk about how growing up on that ranch made you who you are?

Sandra Day O'Connor: I did grow up in a very remote part of Arizona. We always got up early. In fact, on days when we were rounding up, we had to get up by 3:30 in the morning. I think this is in (my autobiography) but one morning I had gotten up at 3:30 as had my father, because we had a roundup that day. I went in the kitchen and we fixed a little breakfast. I don't know what we had, but something to eat before we started out for a long day. I was rinsing the dishes off at the sink and the window looked to the north and a little bit east. I looked out that window and the whole sky lightened up.

It was like there had been a massive explosion and it lightened the entire sky some distance away. I called my father over it and said, "Look at that. That's really peculiar. What do you think that is?" He thought it was very odd. He said, "Well, I really don't know. I think it could be some train going across with a load of explosives." It was during World War II. He said, "It must have blown up on the tracks or something like that."

We couldn't figure it out. The light lasted longer than you would think. It was weeks later when we learned that what we saw that morning was the explosion of the first atomic bomb up at White Sands (Missile Range). We had no idea what we were seeing that day. But see, it pays to get up early, it's OK.

Also, in your book, you talk quite a bit about what your mother and father gave you. Your father obviously gave you high expectations and the love of the land. Your mom taught you to read by the time you were 4.

O'Connor: She was a teacher so she was eager to teach me to read. I was a reader and they loved to read. We had a pretty good library for the remote place that we were living in. That was nice. I often would have my nose in a book when my father would come in and say, "OK, why don't we go up to tank two and deliver some salt blocks?" And I'd say, "Oh, I don't want to do that, I'm in the middle of my book."

Then he'd have to find some excuse to get me to give up my book. Some surprise he had for me to see along the way. Then I'd go and we'd have a wonderful adventure. I don't think they had high expectations of me as such. It was just that whatever job I was given to do, I was expected to do it well. Now if I did, I never got a "thank you" or "well done," but if I didn't, I sure heard about it. I think that's just the cowboy ethic. You do what you have to do and you're expected to do it correctly. If you don't, you're going to hear about it.

If your sons were to write a book about you and your husband, John, what it was like growing up and what you instilled in them, what would they say?

O'Connor: Well, it might be a lot of ranch stuff, too. I was a working mother. The thing that I would worry about the most with those children was I didn't want them to have any free time on their own after school before I got home. Because heaven knows what would go on, I didn't want that. My greatest effort was put into finding some activities that they were engaged in that would keep them busy until I got home. That was a challenge. In the summer was the hardest because they were not in school. Now the Navajo have a theory and it is this, that all discipline of children should be carried out by the mother's brother. All right.

My brother was out at the Lazy B because after he graduated from the University of Arizona, he went back to the ranch. It was a big job and my father was getting older, and so my brother was there. He was very active in the ranch, and they were agreeable to having our children come in the summer to the Lazy B. That was great for me because I knew they were busy, because the minute they got there, they'd be put to work doing things. But it was things they loved. My brother would let them drive the pickup truck, shoot rabbits and all the things kids would just adore to do. They thought he was fabulous. To prove it, this was the '60s when all kids wanted their hair long. Well, they'd get to the ranch and my brother would say, "Well, sit down. First thing we're going to do is cut your hair." And they'd say, "OK." They wouldn't say OK to me, but for him they would. So it's the mother's brother, remember that.

After you graduated from Stanford, spent some time in Germany, you came back to Phoenix. This is 1958. And, of course, law firms still weren't hiring women.

O'Connor: I got out of law school in 1952, in the middle of the last century and things were different. And 1% of law students in those days were female across the country. One percent. That's what it was at Stanford, too. And I was very naive because I never thought for a minute when I was in law school that I'd have trouble getting a job. It never occurred to me. And I got out and here are all these notices on the placement bulletin board for Stanford Law grads, "Call us, we want to talk to you." Well, I called every single number and not one of them would even talk to me. Not one.

And I had an undergraduate friend at Stanford whose dad was a lawyer in a big law firm in Los Angeles. And I said, "Could you talk to your father and see if I could get an interview at the firm?" She did, and he did, and I went down to Los Angeles and met with this distinguished partner. "Oh, Miss Day, you have a fine resume here. But Miss Day, this firm has never hired a lawyer who's a woman. And I don't see the day when we will. Our clients wouldn't stand for it." Well, I'm sure I just said, "Oh, how can this be?" And to cheer me up, he said, "Well, Miss Day, how well do you type?" I said, "So-so." And he said, "Well, if you can type well enough, I might be able to get you on here as a legal secretary." But I said, "No, that isn't what I wanted to do. And thank you." So that was that.

And I learned via the grapevine that the county attorney in San Mateo County just north of Stanford had once had a woman lawyer on his staff. And I thought, "Aha, he had one, maybe he'd have another one." And I contacted the office to make an appointment to see him. And I did. And he was charming. We had a nice visit and he showed me around the office, and he didn't have many deputies at the time. And he said, "You have a fine resume." He said, "I'm sure you'd do a good job. And yes, I had a woman lawyer here and she did a good job. I'd be happy to have you." But he said, "I get my money from the county board of supervisors and I don't have any money to hire another deputy. I'm out of luck here."

He had taken me through the offices and he said, "And as you could see, I don't have an empty office to put another deputy." So I went back to the Lazy B Ranch and I wrote him a long letter. That letter's now in the museum in San Mateo County. He never threw it away. I told him all the things I thought I could do for him, and I let him know that I would be willing to work for him for nothing until he could persuade the supervisors in time that he needed a little more money. And I said, "I know you don't have room. But I met your secretary. She's very nice, and I'd be happy to put a desk in next to hers if she'd have me." That was my first job. He took me, no pay, and I put my desk in with his secretary.

I'll tell you something, I loved my job because I immediately started getting legal questions to answer that had been submitted by the various county officials and officers and boards and commissions. I was doing civil, not criminal, work and I absolutely loved the job. So it was good. And I had been there about three and a half months when he was made the county judge and that opened a vacancy. My supervisor was made county attorney, and then I had a bona fide job with pay and an office. How about that?

In 1969, you asked for and were appointed to an Arizona Senate seat. You later won the election and became Senate majority leader. Later, when you were talking about your public life, you gave a quote from Margaret Mead. It said, "If women want real power and change, they must run for public office and use the vote more intelligently." Can you talk about women in public office, how important that is and what you meant by that?

O'Connor: Well, it was terribly important to us back in the 1960s and '70s and '80s because women in this country held a very small percentage of positions in Congress and in state legislative bodies. It was too small. They just weren't holding public office in any great numbers. And so I thought Margaret Mead was right in suggesting that women had to be much more active in trying to hold jobs like that.

It should just be the norm and accepted that women are going to hold offices at every level and participate in every way. That's what it's all about.

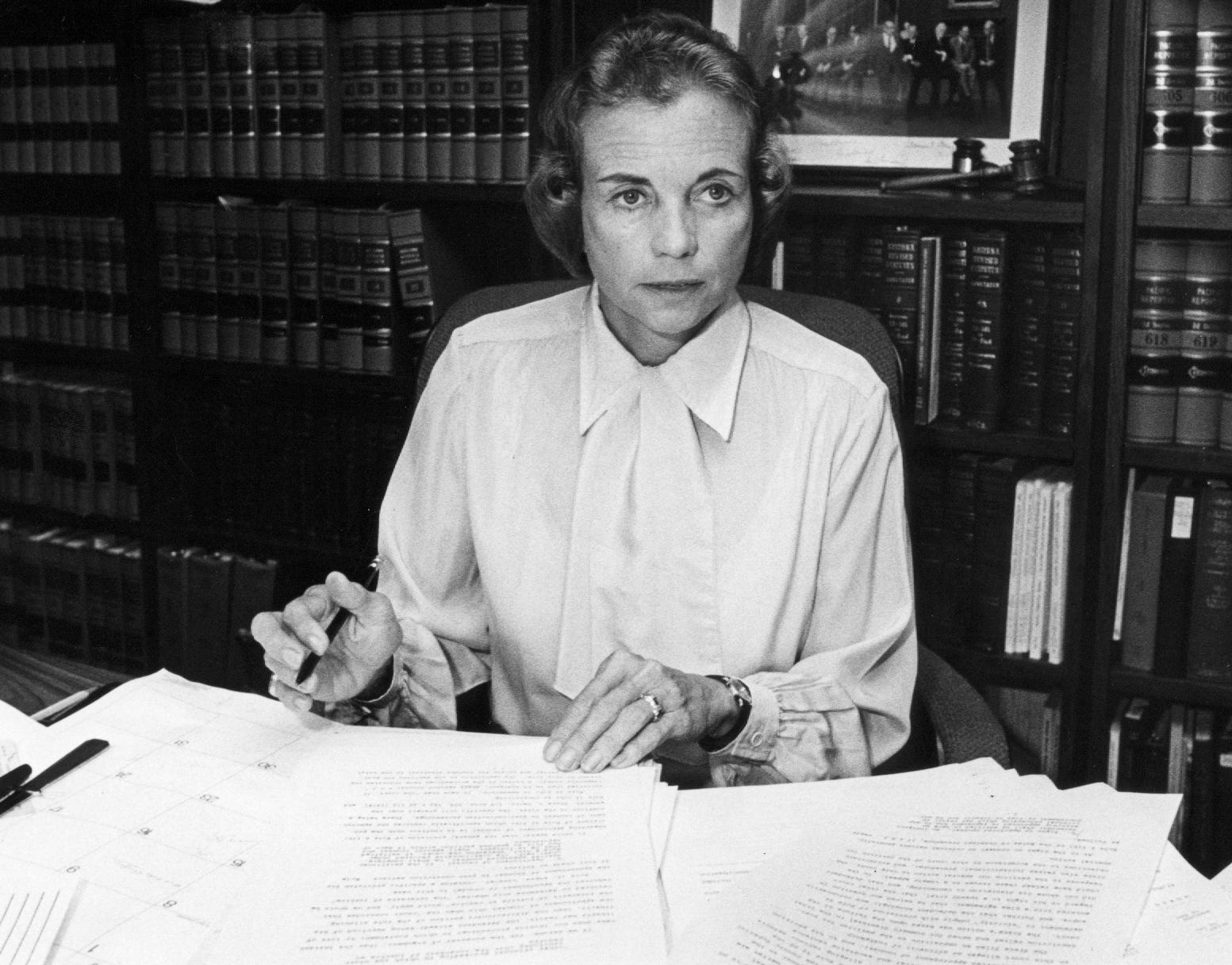

In 1981, this is the big moment when you were on the short list for the U.S. Supreme Court and you had a 45-minute meeting with President Reagan, and afterward you said you weren't so sure you were going to get the job.

O'Connor: Oh, I didn't think I was. I breathed a big sigh of relief, frankly. I mean, no. It was inconceivable to me that I would be asked to serve on the court. For one thing, my classmate, my good friend, my fellow Arizonan, Bill Rehnquist, was already on the Supreme Court. Now, you don't put on the Supreme Court close friends and classmates and people from the same state, that's one of the things you don't do. So I thought it was just inconceivable.

I was very interested to go back to Washington and meet the president's top Cabinet officials and talk to him and go in the Oval Office. That was heady stuff for somebody from Arizona. But I didn't for one moment think I would be asked to do that. And when I got on the plane to come back that afternoon, I just breathed a big sigh of relief and said to myself, "Well, that was really interesting, but thank heavens I don't have to go do that job."

So you get called and you get offered the job. Now what are you feeling?

O'Connor: Well, my heart sank, frankly. It did. It did. I really didn't want it. I'll tell you why. It's fine to be the first to do something major, but I didn't want to be the last. And if I took it and didn't do it well, it might have been the last. And I just thought that was kind of high risk. And so it was my husband who said, "Of course he'll ask you, and of course you have to do it. You'll do fine." Well, what did he know? Anyway, I said yes, and it started the next 25 years, the next chapter.

We had to sit down in that office and figure out how to run an office at the U.S. Supreme Court. I didn't have a single person in there who had ever worked at the court. We had no clue how the paperwork flowed. There is no how-to-do-it manual for a new justice, nothing. Nothing. And all the justices, "Oh, let me know how I can help." But then they go back to work, and that's that. And we didn't know. And the basic things, how did the petitions for certiorari get treated? How do they come to you? In what order? How do you deal with them? What do we want to vote to take? What don't we... We didn't know anything. And the four law clerks and I piled all the petitions for certiorari – there were thousands of them; they'd accumulated over the summer – we piled them on the floor in the chambers, and we sat there and each of us took two chambers at the court to find out how they handled things. And then we tried to pool our knowledge and figured out how the O'Connor Chambers should operate. And it was a real challenge. My goodness.

You learn the hard way. For instance, I had a call a couple of years later from one of the justices saying, "Sandra, how'd you like to write the dissent in case X?" He said the case. And I looked at my notes and I said, "Well, I wasn't sure how I should decide that case. When we talked about it at conference, I reserved final judgment on it because I wasn't really sure. Could I pass for now?" He hung up on me. Clank. Well, unwritten law, if you are asked by a justice senior to you to write the dissent and if the justice has the authority to make the request, it's a request you can't refuse. So I really got myself in trouble. Well, I didn't know, nobody helped.

So it was a tough situation those early years. And Ruth McGregor helped more than you can ever imagine. She was an absolute godsend to have in that chambers. And if I succeeded at all, it was thanks to Ruth McGregor.

Justice Ruth McGregor: I can't imagine that you could have foreseen in any way the amount of attention that would be given to you that first year. I mean, everybody would come up to you. And it always started out, "Justice O'Connor, I don't want to interrupt you, but," That's what everybody would say and then they would interrupt her. But they recognized you everywhere. The press followed you everywhere. They wanted to know about the menus that you served. They watched you and John move boxes into your apartment.

O'Connor: Well, we learned many months later by accident that some person or persons from the press had been regularly examining all our trash from the apartment in hopes of finding letters or things that they could use. Imagine. That never occurred to me. I was shocked.

McGregor: So over the years, did you work out some ways to deal with that attention?

O'Connor: Well, no. I mean, really. No. I don't know. Life goes on somehow.

It was a big change for your whole family. Your husband, John, had a magazine quote, he said, "Sandra's accomplishments don't make me a lesser man. They make me a fuller man."

O'Connor: He was fabulous. He really was. It's so hard to be a husband of a woman who's in some high position and well known. It's got to be hard. And he was just fantastic. And he was the one who always said, "Oh yes, do it. You'll do great. You're fine." He was wonderful. And he seemed never to resent it at all. Even though he had to give up his position at (his Phoenix law firm) because they didn't have an office in Washington, D.C. It put him on the street looking for work. And no firm particularly wanted to hire him because then they'd be disqualified from coming to the Supreme Court with a case because of that. So, it was certainly not easy for him. And yet he never objected or complained. He was just absolutely amazing. He should have run for public office as a young person because he was so engaging, he would've been terrific. But anyway.

One of your passions right now is the O’Connor House project, a space used to host civic groups. We’d love to hear a little more about that.

O'Connor: Well, John and I, in 1957, he had been drafted and he was in the Army Judge Advocate Generals, and we were in Germany. He took his discharge over there, and we both liked to ski. So we rented a cottage in Kitzbühel, Austria. We kept it until the last flake of snow had melted on the mountains in Kitzbühel. We skied all day, every day, for the entire winter, and it was just heaven. It was just the most delightful thing. So we didn't have any more money, and we had a little black Volkswagen Beetle. We brought it back with us to the U.S. and landed in New York and then started our trek across the country hoping John could find a job. That was the idea, look for work. He stopped in several cities and looked around, and we visited friends and relatives in route.

When we got to Phoenix, we didn't have a lot of friends in Phoenix, but Bill and Nan Rehnquist were living here. They were our friends from Stanford. So we touched base with everybody. He took a job (at a Phoenix law firm), and I was so glad he did. We made friends, and we wanted to have a little house.

We had rented an apartment and I was pregnant and had this first baby, a little boy, and we needed a house, so we wanted to build a sun-dried adobe house. There's burnt adobe that is more like a cement brick, but the sun-dried adobe is just the mud mixed with clay and straw and the things they put in it, and it's just dried mud. You don't want to expose it to a bunch of water, but Phoenix doesn't have much water, so that's pretty good. Anyway, we needed to find out if we could get these sun-dried adobes. Somebody told us about (a man who knew adobe). He said that he could arrange for us to get adobes made out of the Salt River bed in Tempe.

So we thought, "Huh, OK." Then we needed an architect and we didn't have any money. (John) was earning $300 a month, I think, and I wasn't earning anything at the moment. So we found this starving young architect that seemed to have some talent and said we just wanted plans. He came up with a dandy plan, at least we thought it was. Then we had to find somebody who'd build with adobe. So the house went up, and when you build with adobe, you have to have a lot of adobe mud. You put a row of adobe bricks down, and then you have to slop a bunch of mud on top of the whole surface and put the next layer on. Then the wet mud squirts out the joints.

John and I had to scrape every joint in that house with electric conduit to make it look like the joint. Then we had to paint the adobe walls. We didn't want them plastered. We painted them with thin coats of mud. Then we finished it by painting them with skim milk. The casing in the milk dries, and if you have regular milk, there's too much fat in it and it doesn't work, but the skim milk with the casing works. The result was just, I thought, fabulous. We loved it, and so that was a great place to be.

Later, we had some additional property, and we put a pool and a guest house and a dance floor, 'cause we liked dancing. It was a great place. I used it all the years we were here in Phoenix to have groups with which we were associated meet and talk about things and get things done.

I had agreed with the State Department of the U.S. that we would accept foreign visitors who came through and we'd host them, take them to dinner or lunch and touring around. Lots of people wanted to come to see Grand Canyon, so we'd take care of them here. We met so many interesting people from countries all over the world and entertained at that house.

We would use that house, the patio, the outdoor area to get people together, make a little Mexican food and open some beer and have good conversation that could lead to action. So when we moved to Washington, D.C., in 1981, we needed money because housing back there is much more costly than here. So we had to sell the house, and that was very sad because it isn't the kind of house that most people would want, an old adobe that would melt in the rain.

So anyway, we sold it and eventually it was resold and then resold again, and the owner decided to tear it down. That was when friends here in the valley said, "We think the house ought to be saved." They formed a charitable corporation and tried to raise a little money to relocate the house. I said, "You can't. It's an adobe house on a concrete slab. You can't do that." They said, "Well, we think we can. We found somebody who thinks they can." Believe me, it was hard. But it now has the most beautiful home site on a hill adjacent to the Arizona Historical Society Museum.

I went in it for the first time yesterday, and I must say I had tears. It was overwhelming to be there and see it, and it looks perfect. It's just back to the basic original house, but it is just wonderful. I want you to go.

I thought that in light of today's world and the difficulty we're having today in getting along and accomplishing things at the national level and at the state level too, that maybe we could use that house to promote the notion of civil talk, which can lead to civic action.