In this podcast episode, charismatic Pati Jinich–Mexican chef, cookbook author, and star of the PBS series “Pati’s Mexican Table” and “La Frontera”–sits down with David and Amy to talk about Mexican cuisine.

Follow on Apple | Spotify | Stitcher | Amazon | Google | iHeart | TuneIn

☞ If you like what you hear and would like to support us, even $1 will help! Thank you.

Chat With Us

Have a cooking question, query, or quagmire you’d like Amy and David to answer? Click that big-mouth button to the right to leave us a recorded message. Just enter your name and email address, press record, and talk away. We’ll definitely get back to you. And who knows? Maybe you’ll be featured on the show!

Contents

Transcript

Pati Jinich (00:01):

I always tell my kids, oh, I’ve got good slang. And they tell me, Ma, that’s from the ’80s. Don’t brag about that.

Amy and David’s Food Week

Amy Traverso (00:08):

Hey, David.

David Leite (00:16):

Hey, Amy. How are you?

Amy Traverso (00:18):

I’m pretty good.

David Leite (00:19):

How was your week?

Amy Traverso (00:22):

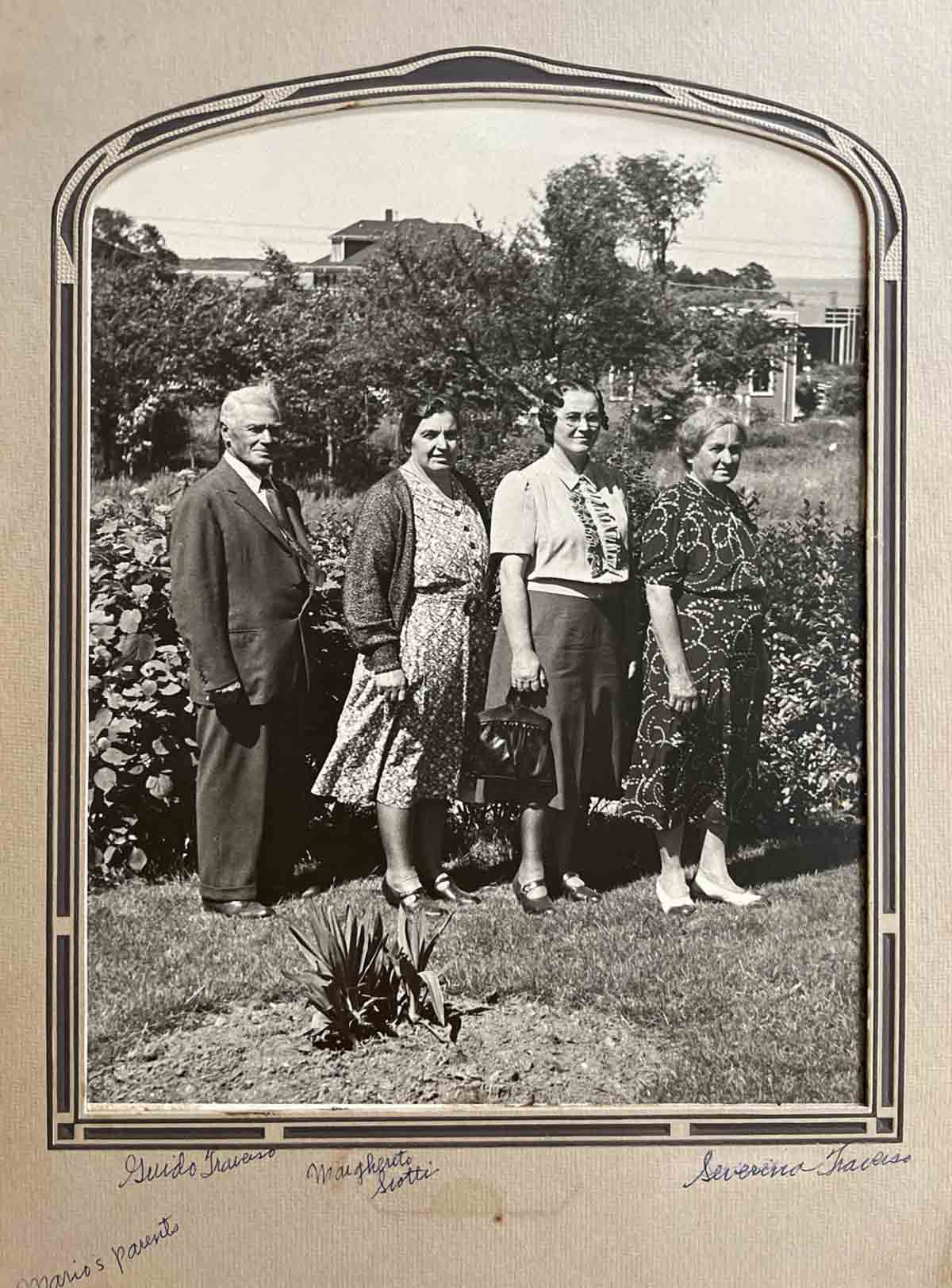

It was great. I heard the coolest story. I had a great-grandmother named Severina Montecucco Traverso.

David Leite (00:30):

Oh, wow.

Amy Traverso (00:30):

And here’s what I learned. She trained under a French chef at this very beautiful estate in Piemonte, where she met my great-grandfather. He was a musician, I understand. He was the second son; wasn’t going to inherit anything. And so she marched herself down to Genoa, she left her kids with her mother-in-law, and went to America. When she got to Ellis Island, they said, what can you do? She said, I can cook. They sent her north to Boston or to Plymouth, Massachusetts, where she cooked for the men who were digging the Cape Cod Canal.

David Leite (01:06):

Really?

Amy Traverso (01:07):

It was her cooking that brought the Traversos to America. She saved enough money and went back and brought her husband and children to America. But I knew she had done that. I knew she had cooked for the men. I didn’t realize she was so formally trained and was such an accomplished cook.

David Leite (01:24):

So you just found that out?

Amy Traverso (01:25):

Yeah, so that was exciting.

David Leite (01:27):

Oh, wow.

Amy Traverso (01:27):

And I’ve been doing some really fun baking, made some shortbread with cardamom and almond, and they’re just really delicious. So I’ve had a good food week now.

David Leite (01:34):

Now, is that her recipe?

Amy Traverso (01:36):

No. This was a recipe I’m developing for Yankee.

David Leite (01:38):

For Yankee Magazine.

Amy Traverso (01:39):

But I got a good food week, and I feel like I’ve found some ancestral connection to cooking, which is really nice.

David Leite (01:44):

Wow. That’s fascinating.

Amy Traverso (01:45):

Yeah. How about you?

David Leite (01:47):

Well, mine’s far less poetic than that. It’s much more prosaic. It’s just, have you ever cooked or grilled bavette?

Amy Traverso (01:57):

No. I’ve done flank steak, but not bavette.

David Leite (02:00):

Bavette is not quite flank steak. They come from the same general area, and it’s a little bit higher up, but I’ll tell you it is amazing. I always think of flank steak as one of those things that you have to quick-sear and can be tough. This wasn’t. And had a little bit of fat on it, but it was just so incredibly tasty that I don’t think I want to cook flank steak anymore. I think I want to cook bavette. And “bavette” is the way that French say it, so it sounds so much more classy than flank steak or flap steak. I’m cooking bavette.

Amy Traverso (02:30):

Right. That sounds great.

David Leite (02:31):

So that really is the only major thing that I had this week. And certainly not as beautiful and poetic as your grandma leading over the entire family to America.

Amy Traverso (02:40):

Well, we have a very exciting guest this week, Pati Jinich [pronounced “he-nitch”], who is, I just love her. She just radiates–

David Leite (02:46):

Her energy is amazing, isn’t it?

Amy Traverso (02:48):

Amazing. Amazing! She just makes you feel so welcomed and so excited to do what she does.

David Leite (02:52):

So what was the most interesting part about what she said for you?

Amy Traverso (02:57):

Pati is such an incredible authority on Mexican cuisine and has really made it her career to travel the country and explore all the regional cuisines that you may have never heard of. So getting her talking about that and the things she’s discovered in each state, each of the 31 states of Mexico, was so fascinating.

David Leite (03:16):

For me, it was that incredible salsa that she talked about with all the nuts and pistachios and walnuts and all these, it just, it makes you want to run out right now and make that.

Interview with Pati Jinich

Amy Traverso (03:26):

Yes. Yes. When she talks about food, I immediately want to start cooking.

Amy Traverso (03:30):

Well, welcome to the show, Pati.

Pati Jinich (03:35):

Thank you so much for having me on. It’s such a treat for me to be chatting with you guys.

David Leite (03:40):

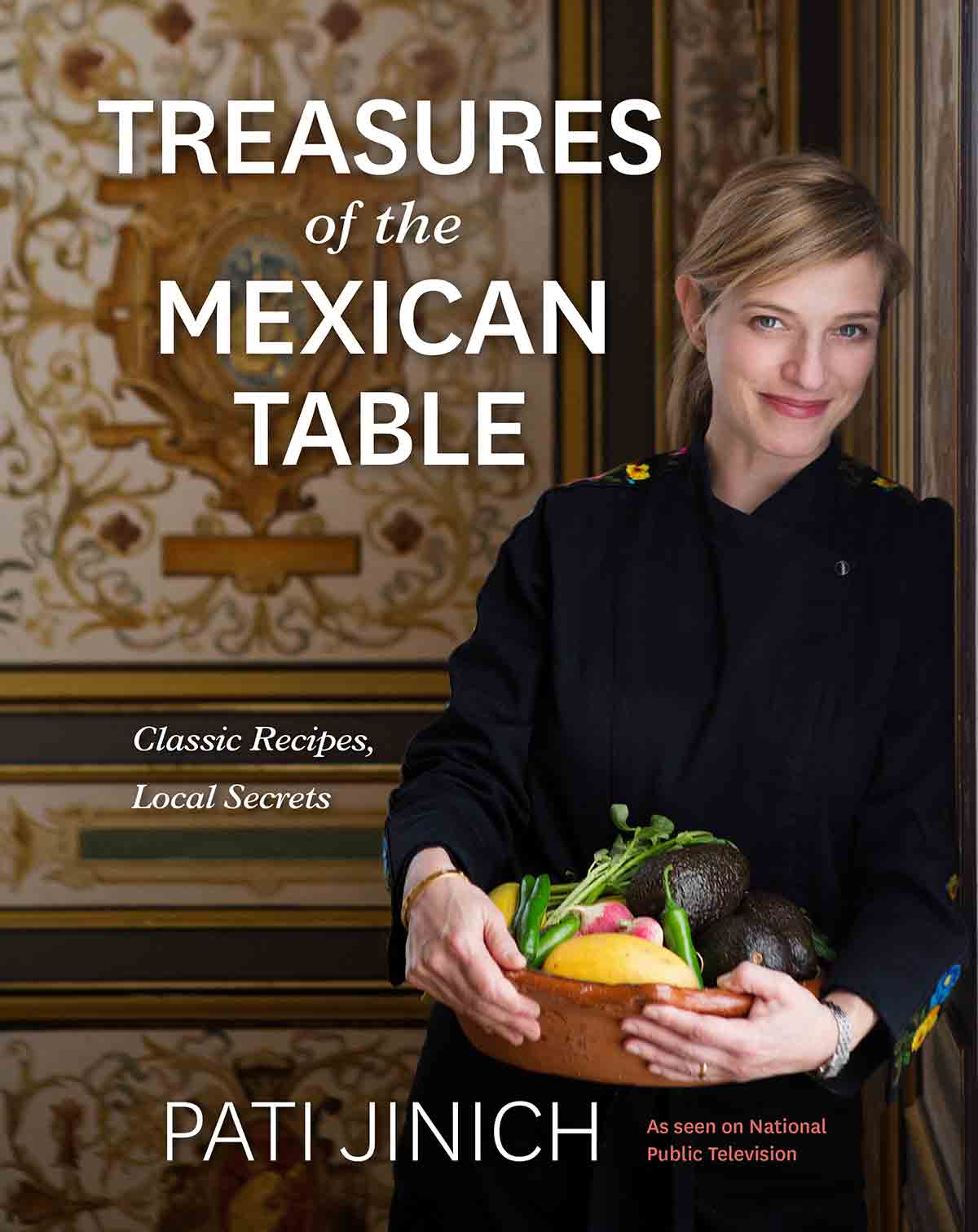

Us too, and congratulations on Treasures of the Mexican Table. It’s a New York Times‘ bestseller. And our recipe testers, we have about 200 of them, they absolutely loved the book.

Pati Jinich (03:51):

Oh, I am so happy to hear, David. And that just makes all that work worthwhile.

David Leite (03:56):

Doesn’t it?

Pati Jinich (03:57):

When people are cooking your food and they’re making those recipes their own, that’s just the best feeling. So thank you for that.

David Leite (04:03):

It is.

Pati’s Background

Amy Traverso (04:04):

So we’ve established we absolutely love your work, but what’s so interesting to me is that this work came about a little bit as a pivot for you. So could you just tell us a brief history of how you went from a political analyst to a celebrity chef?

Pati Jinich (04:21):

Absolutely. And I always tell my kids, I have three boys, well, three grown-up men now. And I always tell them, as they move through life and have to make decisions, I always tell them don’t research too much because I switched careers mid-life when I already had kids, and I thought I wanted to be an academic and a political analyst.

And I was very afraid of taking the plunge and making a very radical left turn. And I always say, whatever you do that comes from another field will only help you and give you a fresh perspective in what you are doing.

So at the time, it was daunting. So I was a political analyst, trained in Mexico, did a Master’s in Latin American Studies here in Georgetown, worked in a think-tank, worked for many years, trying to work on teams that had to do with strengthening democratic institutions and civic culture. Then I was just very hungry to connect with people in a way that really made a difference. I found that things just made sense for me much better if I ate them.

Then I realized how many layers, how much we can share, how much we can tell through food. And I switched careers and I haven’t looked back.

Amy Traverso (05:41):

Wow. So cool.

David Leite (05:42):

Did you have training as a chef?

Pati Jinich (05:44):

Yes.

David Leite (05:44):

Did you just go to school?

Pati Jinich (05:48):

Yes, David. So I trained first as a political analyst. And I’m a researcher, hardcore researcher at heart. And when I decided to switch careers, and I wanted to move from being a political analyst to a food writer, that’s what I wanted to do, I felt that I really needed the academic, the theoretical chops. I needed to know what I was going to be writing and talking about.

Culinary School

So I enrolled in cooking school in L’Academie de Cuisine in Gaithersburg. It has closed since then, but it was a great school. And it really gave me that theoretical backbone, but it also showed me a lot of what was lacking in this global world because everything that was taught to us was very Eurocentric, which of course, it’s very important to Latin cuisine and Mexican food as well because there’s such an intermarriage of old world and new world in our food.

But I saw nothing of our historical techniques like the charring, the roasting, the nixtamalization, or ingredients. So I came up from that very grateful from all I’ve learned, but wanting to write a curriculum about how to approach Mexican food. And that’s when I approached the Mexican Cultural Institute here in DC and said, we should have a Mexican cooking program that approached Mexican food from that historical, analytical point of view. Let’s study Mexican food through history, through the regions, through the different influences. And that has really marked my approach since then.

Garlic, Chile, and Cumin Roast Chicken

Amy Traverso (07:30):

Wow.

David Leite (07:30):

It’s interesting that you’re talking about this because… can you give us a brief outline of the roots of Mexican cuisine in Mexico? Not the European influence yet, but in Mexico.

Pati Jinich (07:42):

Absolutely. And this is so fascinating, David, because, I started “Pati’s Mexican Table,” which is my cooking show that has been on air for, we’re going on our 11th season. And I started “Pati’s Mexican Table” and the cookbooks I write to open a window into everything that I was missing from Mexico, its food, its culture, trying to break myths and misconceptions. And along the way, what I’ve realized is how little I knew, as a Mexican, of my own food and country and how little Mexicans know so-

David Leite (08:14):

Interesting.

Pati Jinich (08:15):

Before the Spanish arrived in Mexico, Mexico had many different Mexican civilizations that make Mexico today. But you had the Mayas, which were very different from the Aztecs, from the Chichimecas, from the Totonacas, from all these different tribes that had some common denominators like the use of corn and beans and chiles. And then, that combined with the Spanish colonial world that dominated Mexico for 300 years–and from that intermarriage, we get the classic Mexico that we learn and know.

But then after that, the history books also forgot or attempted to submerge many immigrant waves that are crucial to understanding Mexico, like the African immigrant wave. There were 300,000 African slaves that came into Mexico. And then the Asians, the Japanese, Chinese, Filipinos, the Jews. Here’s my family showing up in Mexico fleeing from one thing or another, the Lebanese, the Syrian. So in my quest to show Mexico to the US, it became an education for me and my fellow Mexicans as to what is Mexico.

David Leite (09:43):

That’s fascinating.

Amy Traverso (09:44):

Really fascinating. And when we think about what we know of as Mexican food in the US, it is the thinnest sliver of the top of a mountain.

David Leite (09:53):

And I don’t think most of us think of Mexican cuisine as being so richly layered and so, so much input from other countries. We don’t think of that. We think of America as being the big melting pot. Mexico is also a very big melting pot.

Pati Jinich (10:09):

Exactly. So you have all these waves that are just crashing into each other. So you have the evolving Mexico, the Mexico that continues to evolve. Every time that I come back to Mexico, I’m learning something new.

To give you an example, my new season of “Pati’s Mexican Table,” which I hope you’ll watch, it will premiere this fall, I go to Nuevo León. It’s a Northern Mexican state that I’m embarrassed to say I have never, ever been before. That’s where Monterrey is. And I didn’t know it was a state established by Sephardic Jews that were fleeing the inquisition established by the Spanish colony. And they came to Mexico as Muranos as converts, and then they were fleeing the inquisition, established Monterrey in the north. So Nuevo León is very different from the south of Mexico, very scarce. There’s very few ingredients, and they’ve made so much of those ingredients.

So you have the cabrito, the goat that’s cooked on a spit comes from that. You have the flour tortillas. Listen to this. As a Chilanga, a Mexican from Mexico city, I used to think that flour tortillas were an American thing. And even as a grownup woman, when I moved to the US, and I was a trained historian, and I was doing political analysis, I saw flour tortillas as an American thing. And it’s so humbling to realize that the Northern states of Nuevo León, Sinaloa, have been making flour tortillas since the 1500s. And a good flour tortilla can give any corn tortilla a run for its money. And I used to say–

Coconut Shrimp

David Leite (11:58):

I agree with that.

Pati Jinich (12:00):

So they’re deeply Mexican too. So we have all these puddles of ignorance. And at the same time, you get to learn everything that’s in Mexico and that continues to evolve in Mexico because there’s still immigration, and there’s still evolution and creative shapes playing with ingredients. But then, you get this other wave that’s coming the other direction where Mexican food knows no borders. Mexican food is completely borderless, and you have phenomenal regional Mexican food in the US. You have New Mexican, Tex Mex, California Mex. And it makes people very afraid, I think.

Amy Traverso (12:42):

Huh.

David Leite (12:43):

Now, why is that? That’s interesting.

Pati Jinich (12:46):

I think it’s something to rejoice and celebrate. I think it just speaks to the strength and power of the pillars of Mexican cuisine and culture. I feel like for some Mexicans, it’s safe to say real authentic Mexican food is south of the border and runs that. And for many Americans that are purists in Mexican food, they say, oh, anything north of the border is a bastardization of Mexican food.

I guess it’s a way, as human beings, we’re all flawed. It’s a way to try to control and label and put things in boxes because it’s easier for us to understand the world if we categorize. Thinking that we live in a flowy thing, it’s scary. But you have “authentic.”

I think that’s a completely overused word. And so I love to say authentic is whatever is good for you and whatever you grew up eating. There are so many Mexican communities that either existed in the US before the US became the US, or that have moved to the US and have brought their techniques and ingredients and grown roots in the US, and started making Mexican food with the ingredients they find in the US, creating new, delicious mouthwatering, Mexican foods. Who’s to say that’s not good or authentic?

David Leite (14:11):

Exactly. That’s no less authentic than something that was created in the middle and the heart of a state in Mexico. That same thing happens and, Amy, tell me if this happens in your heritage too, but my family’s from Portugal. And if something is slightly different based upon what someone else made, it’s not authentic. So when the waves of Azorean immigrants came to America and they were including local ingredients, the Portuguese back home said that’s not authentic. And I disagree. I think it is authentic. I grew up with things they didn’t eat back in Portugal. It’s because my family did with what they could with what they found.

Pati Jinich (14:47):

Exactly.

David Leite (14:48):

And that’s authentic. That’s authentic.

Pati Jinich (14:49):

Exactly. You hit the nail on the head. I love it because the more years I’m in the US, the more slang I get. And I think that I always feel like, I always tell my kids, oh, I’ve got a good slang. And they tell me, Ma, that’s from the ’80s. Don’t brag about that.

But I was going to say that is exactly the case. That’s why I feel like, and I love food because I think that it gives us this opportunity to understand the world in a way that it’s daunting for the brain. It’s good as a rational animal because you’re eating it, you’re enjoying it. Sometimes you don’t need to understand things. You just need to, you know, I want to eat that food, David, and say this is something amazing.

And if it is from Portugal, if it is from here, what’s worthwhile for me is that it’s absolutely delicious, that it has a story. And I think that that’s why I get baffled sometimes when I see a lot of restrictions in the food world, and people saying these are the people who can cook this, and this is what is authentic, and this is what is right and what is wrong. Because I think that the beauty and the noble character of food is allowing us humans to go beyond labels. And that just happened to me in an outrageous way when I was filming “La Frontera,” which is a docu-series that I’m working on borderland food.

David Leite (16:25):

Border cuisine.

Pati Jinich (16:26):

Yes. I used to think that Mexican food was demonized and had so many preconceptions and misconceptions, even though people love Mexican food, people are always judging Mexican food. But border foods and Tex Mex food and Mexico food and all the foods from the border are so criticized.

And when you get down there, and you eat the food, it’s so vibrant, it’s so raw, it’s so free, it’s so delicious. It’s dishes that are holding on tightly to tradition while they’re breaking new ground at the same time. And then there’s this delicious tension that, in my experience, I’ve only tasted at the border. And I think it’s hard to understand if you’re not there or if you’re not eating the food. And it just has shown me how limited we are in our brains, in our minds.

David Leite (17:27):

Yeah, it’s true.

Amy Traverso (17:31):

I lived in New Mexico for a couple of years and the cuisine there is, I mean, it’s a beautiful, amazing, rich, diverse, perfect cuisine in my mind. So I’m with you on that.

So you just spoke to something that I’ve been thinking about, and David has as well, which is I think a lot of Americans became familiar with Mexican food beyond Tex Mex through the work of people like Rick Bayless or Diana Kennedy. And they’ve done excellent work, but I think right now there’s also a question of do we need American or British translators to be explaining Mexican food to the majority of Americans?

Pati Jinich (18:07)

Yes. And I think that’s such an important point. I feel that when I started “Pati’s Mexican Table,” which was excruciatingly difficult to get off the ground. I mean, it took me over three, four years. And the biggest part of it, the biggest obstacle was my accent! A lot of people, networks and WETA and APT, too, they were worried about people not understanding my accent. So my accent was one thing, and then also a lot of people thinking that Mexican food was too ethnic. Of course, we’re talking about 10 years ago.

Amy Traverso (18:46):

That’s so crazy.

David Leite (18:46):

Of course. Yes.

Pati Jinich (18:48):

Everything that I was saying was why do we need to get taught what Mexican food is by non-Mexicans? Why can’t Mexicans share Mexican food?

David Leite (19:00):

Exactly.

Pati Jinich (19:00):

Why can’t Chinese share Chinese food? And with our memories and histories and language, this has been….so “Pati’s Mexican Table,” when I started the show, we used to translate everything that I did in Mexico. Slowly but surely, everything that we do in Mexico now, we subtitle because–

Amy Traverso (19:24):

That’s great.

Pati Jinich (19:24):

The audience has changed. It has opened. It’s willing to listen to a dialogue in Spanish. Most people prefer that genuine conversation with subtitles.

David Leite (19:35):

Yes.

Pati Jinich (19:35):

But 10 years ago, you couldn’t do that. But I also think that then there’s the politically-correct police, right? So I think everybody has a right to cook Mexican food. Everybody. And if you go to Mexico and learn and want to share it, by all means. If you want to open up a restaurant, by all means.

To give you an example, there’s a fabulous restaurant here in DC that’s called Tiger Fork. The chef is Peruvian. The cuisine is Chinese food, mainly from Hong Kong. It is extraordinary. He lived in Hong Kong. He trained in Hong Kong. He came back and he’s passionate about Hong Kong and China, why can’t he? Well, he did, he could, and it’s phenomenal. And he’s honoring the cuisine and he’s giving credit to where he’s learned.

And he took the time and he spent his years learning. And so I think there’s a way to do it that’s okay. But I also think there’s the extreme that says if you’re not Mexican, you can’t. And then there’s the shades of gray. Do you have to be a certain color to cook something? Because people don’t understand either that in Mexico, there’s all colors of people that are Mexican. And so I guess we get boggled down in all of that.

David Leite (21:03):

And so you don’t have a problem with an American chef or cookbook author becoming the voice of Mexican cuisine in America? That doesn’t bother you?

Pati Jinich (21:13):

I mean, I think that we’re past that time because I think with media and social media and all these fabulous voices, there are so many people that have their own channels. I don’t think one can say that there is one voice.

Amy Traverso (21:30):

Right.

David Leite (21:31):

Not anymore. Exactly.

Sanborns’ Swiss Chicken Enchiladas

Pati Jinich (21:31):

I think not anymore, which I think is a phenomenal development. There’s this diversity and richness of voices that speak to a culture of a cuisine. And I think we should all embrace that. I have absolutely no problem with anyone anywhere in the world cooking Mexican food. And what I always say is here, I’m sharing a recipe for, say, authentic Mexican Swiss Enchiladas (above), which are authentic in Mexico from Sanborns. They happen to have so much cream and melted cheese. They’re called Swiss because Mexicans used to think that anything that was called Swiss had a lot of cream and cheese. And for Mexicans, we love those enchiladas. Guess who came up with those enchiladas?

David Leite (22:20):

Who?

Pati Jinich (22:21):

It was two American brothers who moved to Mexico in the early 1900s, who opened up Sanborns, a coffee shop, that wanted to have American and Mexican food. And they came up with the Swiss Enchiladas, and they’re the most Mexican thing in Mexico City. So I just think there are all these nuances.

Okay. I’ll give you another example. I was in, I say Tucson. It was so confusing because I was in Tucson one episode a few seasons ago when we were, it was called “The Gateway to Sonora.” So we went from Tucson and we saw how the barrio bread baker was making his bread with wheat from Sonora, and it was just an extraordinary experience. And I was in Tucson eating all kinds of Mexican food. They have great Mexican food.

And we go to a restaurant that’s owned by a Mexican-American woman. Generations of Mexican people that have lived in Tucson before Tucson became the US. And they were selling Nutella tamales. So I took a photo of the Nutella tamale, and I posted it to my Twitter. I mean the politically-correct police jumped on. “Why are you posting a Nutella tamale?” And it wasn’t Mexicans who were commenting on this, which was the interesting thing. It was all these people saying that that was wrong, that that was inappropriate, that that was cultural appropriation to an extreme. Guess what? This was a Mexican woman making this tamale. And guess what? If you go to Mexico, to any panaderia anywhere, you’re going to find Nutella because Mexicans, we love Nutella. Are we not allowed to eat Nutella because we’re Mexican?

Amy Traverso (24:11):

Right. Right.

David Leite (24:11):

Some of this for me personally, Amy, I don’t know how you feel, some of this has gone too far in my mind. I know that I’m thinking about Portuguese cuisine where there’s a lot of Portuguese cooks and chefs who say no one but someone who is Portuguese can write a Portuguese cookbook. I don’t have that belief.

If you know Portuguese cuisine, write about Portuguese cuisine. If you know what it is, where it comes from, the history, and you’re faithful and true to that history, go for it. Otherwise, I mean talking about Mexican food I was just thinking this as you were saying. The only problem with Mexican food is when someone makes bad Mexican food.

Pati Jinich (24:48):

Exactly.

David Leite (24:49):

That’s my only problem is when someone makes bad Mexican food. Otherwise, I am fine with Mexican food because that’s fantastic cuisine.

Amy Traverso (24:56):

I think the problem is not with Rick Bayless making beautiful food. It’s the assumption that used to underlie his success, which was that we needed an American to translate the food for us. I think if Rick Bayless is one voice among many, including, especially including Mexican voices, that’s great. It was the idea that Americans, first of all, it was the idea that everyone in America somehow didn’t know Mexican cuisine as if there weren’t Mexicans here. Then the second, that Anglo-Americans needed a translator. That, I think, to me is the problematic part, not him or his work.

David Leite (25:37):

And I think that, Pati, I think you said it really well. A lot of those strings have been cut because of social media, because of the democratization of media, that anyone who knows about Mexican cuisine or Portuguese cuisine or Italian cuisine can have their own channel and can share their own experiences.

Pati Jinich (25:57):

I agree.

David Leite (25:57):

See what I mean, Amy?

Amy Traverso (25:59):

Yeah. Yeah. This is work that’s happening I think on so many levels. But just dismantling the assumption that a version of American whiteness is the default and needs to be catered to at all times. And that if you’re putting up media, that’s your audience. And I think, thankfully, that assumption is being dismantled and it allows for so much better everything.

Pati Jinich (26:21):

We all tend to look at the past with today’s glasses, right? I remember when I started teaching Mexican food 15 years ago, I cannot begin to tell you how I’ve seen, not only the palette of the American audience evolve, their hunger, their openness, their appetite–

David Leite (26:45):

Their curiosity.

Pati Jinich (26:46):

Their curiosity, but also, and very importantly, the availability of ingredients.

So 15 years ago, you couldn’t find all these dried chiles–anchos, guajillo, chipotle. People don’t know, didn’t know what you were talking about then. And so it’s just easy to judge things, 10, 15 years ago, 20 years ago. Maybe people needed, wanted certain people to teach them something at a time when there weren’t the ingredients available.

I mean, luckily and thankfully for all of us, there are so many Mexicans here and so many people that love Mexican food. And trade has evolved and you have online shopping now. You can get this dried chile in your grocery store, in the middle of wherever you may live, you can get it online. But it’s also having the access to the ingredients, the access to the information readily available in your Instagram feed or your computer or whatever it may be. The channels were less, were more limited. They were, as you were saying, much more controlled.

So I think now there’s this unbridled source of ingredients and content, and that it can be daunting I think. In that river of information, there’s amazing sources and there’s terrible sources. I mean, sometimes the videos that people will share with me, and they’re like, “Pati, what do you think about these?” And I’m like, I’m not even going to comment. People using, and just to get attention, like just a couple of spices over something and calling it “my Mexican thing.”

And I think people want to play, they can play. And people can follow whatever you can follow. And I think it’s also learning to know we can’t control what other people think of culture, food at a certain time. But you can only contribute with, as you guys do, with the best possible content that you can share.

David Leite (28:48):

Yes. I agree.

Pati Jinich (28:49):

And let others do what they must. And then you hope that you find readers and viewers and cooks that will appreciate your content for what it is.

Slow Cooker Tacos al Pastor

Amy Traverso (29:00):

Pati, you were talking a little bit earlier about how many influences contributed to Mexican cuisine. So one example, Pati, I think of multicultural Mexican cuisine that a lot of Americans are familiar with is tacos al pastor.

Pati Jinich (29:14):

Yes. And I think that is a clear example, Amy. The tacos al pastor came to Mexico by way of the Lebanese community establishing itself, not only in Central Mexico, Mexico City, Puebla, but there’s also a very big Lebanese community in the Yucatan Peninsula. So you find versions of Kiva there that are phenomenal and different and made with pork. And then you have the tacos al pastor, which have that fire pit.

And then, there’s another version that comes from the Lebanese community that comes from the state of Puebla, where we have this very strong Lebanese community that has grown such deep roots in Mexico through the centuries. And these tacos are called tacos árabes.

And there in my new cookbook, which you guys have, and here you have marinated pork, very thinly sliced in so much lime and oregano and mint. And then it’s cooked on spit, just like tacos al pastor. But then they serve it, instead of in tortillas, in very thin pita bread. And you dress it with tahini mixed with a lot of fresh squeezed lime, not lemon–in Mexico, we use lemon–and cumin and a chipotle peanut sauce. So can you imagine that combination?

Amy Traverso (30:41):

Oh. That sounds heavenly.

David Leite (30:42):

Wow.

Pati Jinich (30:42):

And thank you to the Lebanese people for coming up with that. And people think, oh, that’s a gyro. It’s made on a pita. So if you posted that on the internet today, the politically-correct police would jump and say, “That is not authentic. Take that off.” But if you go to Puebla, those tacos have been made for almost two centuries. You find special taquerías that only make tacos árabes that have lines at the door. So I think before people jump to criticize a dish or a cake or a cuisine or something, it’s good to just pause and read a little bit about the history of what they’re saying.

Amy Traverso (31:28):

Yeah. So let’s talk about some home cooking things. What is a salsa that we should all be making this summer. I’m actually thinking about the chipotle peanut salsa in the book, which is just calling to me. But what’s a salsa that you want everyone to try.

David Leite (31:44):

That we all should be making.

Salsa Macha

Pati Jinich (31:46):

Well, definitely. I think you guys have exactly what I have in my refrigerator in the summer, which is all these salsas. I have a jar of salsa macha at all times. My favorite take on salsa macha, it’s in my new book, and salsa macha really breaks any idea that you may have of any salsa because it doesn’t have tomatillos, it doesn’t have tomatoes, it’s not saucy.

Salsa macha is like a cross between a wet granola and a chile crisp. It is exquisite, Amy, David. I mean, you cook a little bit of garlic over low heat and olive oil, let it poach, then you add your dry chiles and let them just macerate, not deep fry. I like to add ancho, guajillo, and chile arbol for some heat, but the original uses dried chipotle chiles. You can play with it talking about versions of things.

And then you add the nuts that you like. There’s many salsa machas that have peanuts. I like making salsa macha with a lot of nuts. So I add pistachios and wild nuts and pine nuts. The original salsa macha also has sesame seeds. I add sesame seeds. But I also add, like many Mexican cooks in Central Mexico, I add amaranth seeds.

So you have these crunchy, chunky sauce that has a lot of textures and flavors. And then you add a little bit of piloncillo or dark brown sugar, a splash of vinegar. And you can use that chunky salsa or garnish or condiment or whatever you call it. So you have it in your fridge, and you can make an avocado toast, top it with salsa macha. You can bake potatoes and drizzle with salsa macha.

David Leite (33:32):

Oh, gosh.

Pati Jinich (33:32):

You can make an omelet, salsa macha.

Amy Traverso (33:32):

I’m so hungry.

Pati Jinich (33:37):

You know what you can do with salsa macha that is insane?

David Leite (33:39):

Uh-huh. Put it on ice cream. I don’t know–

Pati Jinich (33:41):

Exactly. Exactly.

David Leite (33:41):

Really?! No!!

Pati Jinich (33:41):

I was going to say you cut some fresh summer fruit like peaches or mangoes, top it with vanilla ice cream or yogurt, and then add salsa macha. And it’s so crazy. You can also top salsa macha over freshly made hummus. Who’s to say you can’t do that? And so talking about authentic, you find phenomenal hummus in Mexico because there’s a Lebanese Syrian community too.

Huevos Rancheros

So I think the salsa macha and the condiments, Amy, you were saying the chipotle peanut salsa. That’s something you can also make. Put it in your fridge and use it for tacos, for quesadillas, for a version of huevos rancheros. I have all these things in my fridge like pickled onions, pickled jalapenos, pickled chipotles. And then you make a tuna niçoise, you make a tuna salad, and you mix it with pickled jalapenos. Condiments really make your life so easy in that you can just take out a can of something, mix it with pickled potatoes and chipotles, and you have a fabulous tuna salad.

Amy Traverso (34:49):

Right.

David Leite (34:50):

Ah. Mexican cuisine has this whole catalog of amazing, incredible marinades for meats.

Pati Jinich (34:55):

Yes.

David Leite (34:55):

But you have to plan for it. So what are some of the grilling things that people can do, some grilling recipes that are great for a weeknight recipe that maybe if they forgot to marinate, they can still do some great stuff?

Pati Jinich (35:08):

Any carne asada. I mean, truly I used to marinate my meats a lot in the way of Mexico City. So I’m a Chilanga by heart. And in Mexico City, we marinate things. We marinate our skirt steak or arrachera or picanha even any ribs that we’re going to grill, or sausages. We just marinate the heck out of them with Maggi sauce, Worcestershire sauce, lime juice, garlic, and chipotle sauce. We just add everything.

Then I went to Northern Sinaloa in Nuevo León, and I learned from them carne asada has nothing but salt on top, and it’s great for them. So there’s the versions of carne asada. So that is something that you can really pull off if you didn’t have time to marinate anything. You go get a good cut of meat. This trick I learned also from the Norteño lands in Mexico, if you clean your grill grates with a half or a quarter of a piece of white onion, it flavors the grill grates, and it adds this ambience to your grilling section/environment. And it just sets the tone to something delicious is about to happen.

David Leite (36:29):

The carne asada.

Grilled Corn on the Cob with Cheese ~ Elote

Pati Jinich (36:29):

And then you use that grilled onion to make a salsa. I mean, I think the carne asada cookout is one of the easiest things because you throw the meat there, you throw your corn there, and then you make corn. You make esquites. You slather the corn with… I love mayo. I don’t know about you, guys. We just slather it with mayo. You do some crumbled Cotija cheese, some ground chile piquin, salt, lime juice. You have your grilled meat. You can make quesadillas on the grill. They’re so delicious.

Cajeta

Oh, these I just learned. So in Nuevo León, they make the carne asada cookouts. And in the same grill where you cook your meat and your vegetables and your tortilla and your chiles and everything, at the end of the meal, they throw flour tortillas on the grill. They drizzle them with dulce de leche or cajeta. [David moans with delight.] They roll them over. If there’s some leftover melted cheese, they throw that in there, too. And you have a ridiculous dessert because you have the tortillas that have that little savory taste, and then the melted dulce de leche, and the clashing combination with melted cheese, and you’re done. You just made everything on the grill.

Lightning Round!

Amy Traverso (37:47):

Amazing. Yeah. That’s perfect. So we’re going to do a quick lightning round with you just top of your head answers, okay?

Pati Jinich (37:52):

Yes.

Amy Traverso (37:53):

All right. So what is your go-to meal when you’re dead tired?

Pati Jinich (37:56):

Quesadillas.

David Leite (37:57):

Best time-saving trick.

Pati Jinich (37:59):

Oh my gosh. I have none.

David Leite (38:00):

You just spend time in the kitchen.

Amy Traverso (38:06):

Your favorite food show or movie.

Pati Jinich (38:08):

Oh my gosh. Well movie, I think “Like Water for Chocolate” for sure.

David Leite (38:14):

Great. Your most beaten-up cookbook.

Pati Jinich (38:16):

Ah, I have a few. Claudia Roden’s, her first cookbook, Joan Nathan’s first cookbook, and Jacques Pépin, “Cooking with Claudine.”

Amy Traverso (38:29):

That’s so nice. All right. Your greatest faux pas in the kitchen.

Pati Jinich (38:32):

I have too many to recall.

David Leite (38:39):

So then your last best thing that you ate.

Pati Jinich (38:43):

Ah, the eggs that I made this morning, which were with nopalitos and a Mexican-style sauce because I have all my boys with me at home, so I’m making big breakfasts each morning.

Amy Traverso (38:54):

Nice.

David Leite (38:55):

Wonderful. Oh Pati, it’s such a pleasure having you on. We hope you’ll come back and talk more about Mexican cuisine with us.

Pati Jinich (39:01):

It will be my pleasure. You guys are such a delight. Thank you for having me.

Amy Traverso (39:05):

Pati Jinich is the three-time James Beard award-winning Mexican chef and New York Times bestselling author. Her latest book is the wonderful “Treasures of the Mexican Table.” Pati is also the creator and host of the long-running “Pati’s Mexican Table” on public television, and the Emmy-nominated “La Frontera” primetime special that debuted in fall 2021. You can find Pati on Instagram at @patijinich.

David Leite (39:36):

This podcast is produced by Overit Studios. And our producer is the spicy Adam Claimont. You can reach Adam and Overit Studios at overitstudios.com. And remember to follow Talking With My Mouth Full wherever you download your favorite podcasts. As always, if you like what you hear and want to support us, please leave a review and rating on Apple podcasts. Chow!

Amy Traverso (40:06):

Oh, I got to think of something. God, I’m really at a loss. Sorry. Can we do that again? I really, I just forgot that I need to think of something.

Bloopers

David Leite (40:24):

I like how you did La Frontera. You were doing a little bit of rolling of the tongue. La Fronterrrrra. Very–

Amy Traverso (40:33):

You have to respect the proper way to say if you can.

David Leite (40:35):

You do. You do. La Frontera.

Amy Traverso (40:36):

But I sound like a dummy.

David Leite (40:37):

See, I say Portuguese in “la fron-tay-ruh,” but it’s the “la fron-tare-ruh.”

This is the first time listening to one of these podcasts, funnily enough, while preparing some food for the following day. I got to say; it is pretty good. Mexican food is one of my favourite cuisines – it is easily in my top 5, but it is somewhat difficult to find in Australia. That includes the big cities. Byron Bay might be the most apropos for getting the vibe.

That being said, it is not impossible. The tortillas, enchilada sauce, salsas and everything ThRcan be purchased from supermarkets and specialty stores (I got one called Sam Coco’s in my hometown of Brisbane, that place has transformed my cooking like never before). But as the senorita here mentioned, you are slivering off the tip of the iceberg with what Mexico can offer to the culinary world.

I was not aware until this podcast that there was a significant Lebanese presence in Mexico. That just goes to show how much of an intrinsic tapestry a cuisine can have. Can that be an offshoot of Lebanese cusine, showing the far reachs of its influence – a bit like Indian-style curries in Trinidad, South Africa (which itself has such a tapestry – one of the world’s unsung gems) and Fiji among others – or maybe a take on a new interesting type of food? An example is in my country Australia, the HSP which is kebab meat, sauces, and garnishes (ilke cheese, olives, pineapple and whatnot) on top of fries. You can find that at any kebab shop, and Middle Eastern restaruants are almost guaranteed to have a version.

Which brings a new angle to hearing that word “authentic”. It may be an absolute nothingness, because of a number of factors making a dish not like it is in St. Elsewhere. And it is best to come from the mouth of the babe.

Thanks, Mikey. We’re so pleased that you enjoyed the podcast. It is the perfect thing to listen to while making a fantastic meal.