When Peter Wien was 10 years old, he started biting his hand, gnawing on it almost daily, his mouth sculpting the soft skin between his thumb and index finger into an arched callus. Occasionally, he broke flesh. Biting was how Peter managed what was happening at camp.

He doesn't remember how the abuse began, only the way it persisted – in the cabin in the afternoon, above the barn, when walking to the lake. He remembers the time the counselor guided him through the trees, took off both their clothes and perpetrated the abuse of which so many don't speak, the abuse we lock inside.

Peter remembers the clearing they would go to and the mossy spot where they would lie, surrounded by the furrowed bark of Sugar Maples and the elephant skin of American Beech. Deeper in the forest around them, trees absorbed the dampness of shadows as confusion ballooned in Peter's belly. Peter remembers climbing the ladder to the barn's loft where costumes were stored for shows, the ball in his throat when he realized the counselor had followed. He can still feel the unsettling abruptness of those moments after the counselor would stop, the unease of all that was left unsaid and unknown.

Peter said the abuse occurred over multiple summers in the late 1950s at Vermont's Camp Najerog, where parents sent their sons for an education on the outdoors. It would split Peter into the boy he deserved to be and the one he would become. The abuse he recalls, and the lingering questions about what the camp did and did not know, what the adults around him did and did not do, would come to define every aspect of Peter's life.

As the abuse continued, Peter couldn't stop biting his hand. His mother and father – perhaps unwilling, perhaps ill-equipped as parents of that generation were to address their son's trauma – didn't look or ask or ever really see. They told Peter that if he stopped biting, when he could eventually drive, they would buy him a car.

"I stopped biting my hand and I started ripping my lip," he said. "My lips no longer join. Over 60 years of ripping away at my lip, it's kind of gone."

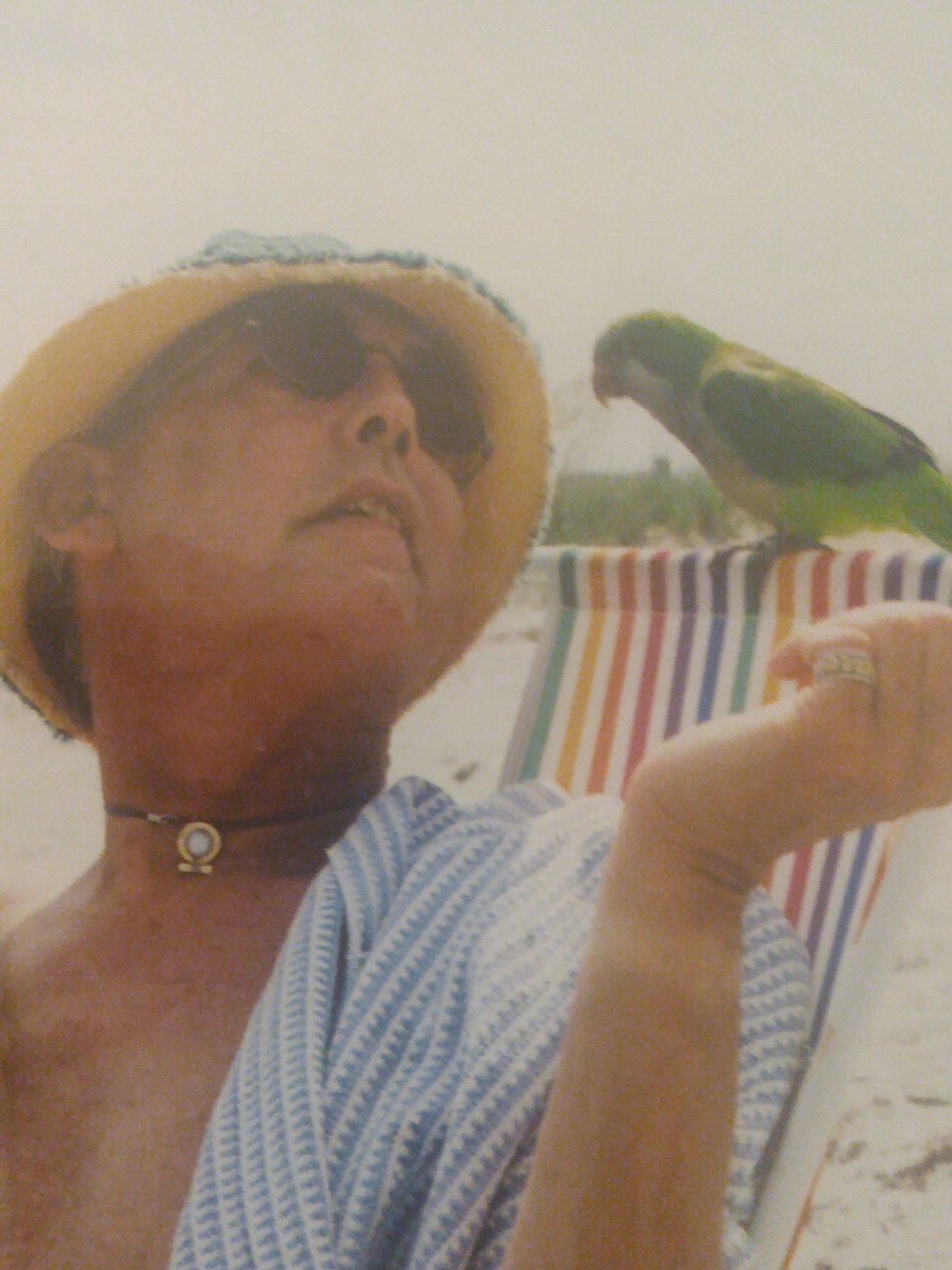

Peter is 75 now, and if time is the measure, he has traveled far. But more than half a century after leaving the camp, those summers are still achingly present. Peter never fell in love, was too afraid to have children, couldn't hold a job. Friends are hard to keep. Therapists, too. He has had more sexual partners than he can count, but never intimacy. He has struggled with his sexual identity. Gay, straight, bisexual – nothing ever really fit. His deepest relationship was with a parrot he rescued and refused to keep in a cage. When the bird died, Peter thought it was probably time he did, too.

Researchers have found at least 1 in 6 men have experienced sexual abuse or assault, and the consequences of that abuse can ripple across a lifetime. The severity of trauma can vary based on existing vulnerabilities, predisposition to mental health problems and access to social supports. For many men, childhood sexual abuse distorts reality, keeps them from connecting with others – from forming the relationships crucial to healing – and leaves them perpetually questioning themselves.

Male survivors face unique challenges because of stereotypes around masculinity that suggest men are not victims, men can handle it, men always enjoy sex. The experiences of male survivors are also complicated by homophobia – 96% of perpetrators against boys and girls are men. Fears of being seen as gay can contribute to feelings of shame and a desire to hide the abuse, especially when their bodies have sexual responses under violence (which is physiologically normal for any survivor).

"I belong to an era of men who were hammered into guilt and silence by our abusers and those who knew of it,” Peter said. “I couldn't turn to people who could see my terror, my frustration, and do anything about it. ... I was a young, innocent child, and I trusted he cared about me. I trusted when he told me that he loved me."

Male sexual abuse is pervasive but has historically been covered up so effectively that even what we know now belies the extent of the problem. This abuse is under-researched and underreported, affecting boys today and millions of adult men who have spent their lives trying to recover from harm that can prove interminable.

Peter has spent more than six decades wondering how his life might have unfolded if not for the abuse.

That answer is painfully unknowable.

He has also spent most of his life wondering if he was the only boy who called Norman Kibby Nicholson his abuser.

That answer we found.

A beloved camp. A lost boy.

Camp Najerog was perched on a hillside above Lake Raponda in Wilmington, Vermont, more than 300 acres purchased by Harold "Kid" Gore and his wife, Jane, for its splendor and possibility – secluded yet accessible, with striking summits, winding trails and a pristine lake. Gore, then the head coach of the University of Massachusetts Amherst football team, said Najerog began as a "little experiment." The camp was established in 1924 and operated for more than 40 years. Gore became a pioneer in the summer recreation industry.

'I was far from the only one': Man recounts sexual abuse at Boy Scout camp in 1970s

Gore's expressed dream was for boys to delight in life in the open. Campers learned boating, swimming, fishing, hiking, horseback riding and riflery, sailing, water skiing and canoeing. They played tennis and baseball, earned Boy Scout merit badges, gardened and cared for animals. Gore also made space for singing and performing, daydreaming, roaming and rest. He intentionally kept the camp small – no more than 50 children, most of them boys and a handful of girls each summer – so it could cater to individual interests.

Counselors would track campers' progress on activities, remarking on adeptness, temperament and potential. It appeared there was a desire to understand each child and to sensitively respond to their needs. A section in one of the camp's binders titled "discipline" suggested that if a child was exhibiting troubling behavior, counselors should search for the causes of that behavior rather than simply punish the camper. Another page on understanding the child featured a typed list of fundamental human desires: "recognition," "affection," "power," "new experience" and "security."

Gore wouldn't take just any camper. One camp brochure said "enrollment is limited to boys whose parents are known to the directors or their friends." The same was true of counselors: "A camp is as good as its counselors. The Gores select leaders known to them personally. They are chosen because of their character, personality and particular fitness for work with boys."

Najerog was beloved. Parents wrote to Gore to remark on changes they observed in their child's behavior when they returned home – in manners, motivation, fastidiousness. Gore received letters from former campers updating him on their achievements. Some campers said Najerog was among the most transformative experiences of their lives.

Peter’s parents learned of Najerog while living in Connecticut, by way of their neighbors, who said many families were sending their children there to teach them how to rough it and develop moral character. USA TODAY confirmed through camp rosters and reports that Peter attended the camp for several summers in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Like many Najerog alums, Peter has a fond collection of memories from the camp – caring for baby Toggenburg goats, water skiing on the lake, sitting on peninsulas under moonlight.

But those memories live alongside ones of being molested, stalked and terrified.

Norman was a counselor at Najerog for several years, well-liked by the administration and many of the boys, and when the abuse first began, Peter said there was a part of him that reveled in Norman's attention. He liked when Norman told him he was special. Peter describes his father, an accountant by trade, as distant, and his mother, a housewife, as self-involved. He had a difficult relationship with his older brother, who also attended the camp. When Norman started looking at him, Peter felt seen.

He remembers Norman would masturbate and molest Peter. Sometimes Norman would talk about his girlfriend. As time passed, Peter began to understand that Norman did not believe he was special. He started reading anything he could get his hands on in the library on pedophilia, sexual abuse and homosexuality, which at the time would have reflected psychiatry's outdated view of homosexuality as sociopathic and deviant. He began to deteriorate, consumed by self-loathing. He wanted Norman to stop, but fear and guilt stopped the words in his throat.

When Peter or his brother misbehaved, their parents threatened to send them to a military academy in New York. When Peter could no longer tolerate the abuse, he begged his parents to send him to the academy – not to Najerog. He wanted to escape Norman and punish himself for the shame of things he did not understand.

Peter said his parents agreed. He heard, later on, that was the summer Norman finally got caught.

'He took my ability to love'

Sexual victimization is a betrayal. It's a betrayal of our belief that the world is a just place and a betrayal of our trust in the people who are supposed to keep us safe. It's a betrayal of our own bodies.

After the abuse, Peter was never the same boy, but back then, many parents still weren't connecting behaviors to feelings, still wouldn't have thought to ask: "Why are you biting your hand? What's wrong? Are you OK?"

Peter kept ripping his lip and burying his anguish, and he started acting out sexually. At 14, on a family trip to New York City, he snuck out of the Waldorf Astoria and took a bus downtown to the St. Marks Baths, a haven for gay men. He remembers eager eyes and foul mattresses, the group cooking heroin and the man who told him to go home, but only after having sex with him. Earlier that day, his mother had bought him a toy plane.

Peter searched for answers in the bodies of others, but he couldn’t disentangle himself from the abuse, couldn’t figure out where he stopped and the violation began.

Peter said, conservatively, that he has had sex with at least 2,000 people.

“I regret every minute of it,” he said.

When a person is victimized at a young age, switches can get turned on prematurely, which can lead to compulsive sexual behaviors. In some cases, promiscuity can also reflect abuse survivors trying to figure out their sexuality. Peter had his first orgasm during the course of his abuse. His arousal is associated with something terrible, and because he wasn't treated, psychologists say it's almost impossible for him to separate that from what he might have inherently desired.

“This perpetrator co-opted (his) entire sexual evolution,” said Abra Poindexter, a licensed independent clinical social worker and psychotherapist who specializes in working with trauma and LGBTQ issues. She has not treated Peter.

Peter describes himself as bisexual, though the label often doesn't feel right. He doesn't have emotional feelings toward male sexual partners. He can develop emotional feelings toward women but finds them so uncomfortable that he can't engage in an intimate sexual relationship.

Peter’s perplexity was likely exacerbated by being a boy in the 1950s perpetrated on by a man during a time when homophobia was rampant.

“I remember sitting in a bar with my best friend; I guess we were probably in college. He was talking – he was very straight. We got on the topic of sex or whatever, and he said, ‘I got to tell you, man, if I thought I was sitting across ... the table from a homosexual, I would get up and pick up this chair and bash him to smithereens because he wouldn't deserve to live.’”

There were several women with whom Peter felt a future could have been possible. But eventually he always felt he needed to escape.

"Norman took something from me that was the most intense violation of my life: He took my ability to love," Peter said.

Friends describe Peter as a contradiction. He's short-tempered, mercurial, often closed-off, but can also be charming and witty and attentive. Darius Batmanglidj, 54, lives a few miles from Peter in Denver. Darius said he enjoys spending time with Peter, but their friendship is strained by Peter's anger and depression. In 2017, after Peter’s bird, Barney, died, Darius said he hit a low.

“I don't remember exactly how it started, but he got verbally abusive over the phone with the people at his bank, and that did not end up well,” he said. “He asked me to take him down to the bank, which I did ... and he ended up getting arrested.”

Peter was found guilty of disturbing the peace.

Friends who’ve known Peter the longest also call him intelligent, scrupulously honest, decent and good. He feels and relates to others deeply. Injustice riles him. Peter can’t tolerate the sight of an abused animal. He does spiritual bodywork to try to heal other people’s brokenness. More than one of Peter’s friends says he has been there for them during the most bitter chapters of their lives.

Vivian Holmes, 72, met Peter at a spiritual group in Connecticut in the 1980s.

“If I couldn't drive, he would drive me someplace,” said Vivian, who has rheumatoid arthritis. “I've gone through several health issues and he's always there to check up on me. … Let's say you can't sleep and it's 10 o'clock at night and you want to go out and do something, he'll figure it out. You need someone to talk to, no matter what the time, you can call Peter.”

A few years ago, Nancy Gyuro-Sultzer, 70, was in the Denver area visiting her daughter when she saw an ad for a man doing energy work. She was intrigued, reached out and met Peter. He gave her a healing session, which uses sound and sometimes touch to improve health. They stayed connected.

Last year, Nancy decided to move to Denver to be closer to her daughter. A part of her hoped she and Peter could become closer, too. She was drawn to his spirituality, his vulnerability, his unusualness. But as her move approached, she said Peter's walls went up. By the time she relocated, Peter had withdrawn.

"He's kind of a mystery to me," she said. "He just kept telling me: ‘This is just me. This is just who I am. This is my story.’ I've heard him say that a number of times, ‘This is my story.’ One time he said, 'This is my story, which has become me over who I am.'"

'Oh God, Norm. I'm so sorry it's come to this'

Peter always wanted to know if there were other boys who said Norman abused them. He heard rumors about the summer Norman was fired but didn’t have details. Did he hurt other boys? How many?

Peter remembers several cabinmates, including Eldred French. Eldred grew up to become an arborist, married Lily and raised three daughters. He also served as a Democratic member of the Vermont State Senate.

Lily picked up the phone on a Monday afternoon and handed off to Eldred. He came to the line pleasant and at ease.

"I knew it was going to be Peter," he said when he learned who passed along his name.

Eldred has not spoken to his former cabinmate since they were children, but Peter's older brother and Eldred's older brother, who also attended Najerog, remained in touch. Eldred had heard a few things over the years, whispers of an old friend's pain. Eldred and Peter had shared summers, innocence, boyhood. And something else, too.

"Norm Nicholson," Eldred said.

Eldred said Norman abused several boys in their cabin: himself, Peter and two others.

He said the four of them talked about it at camp, and he remembers this vividly, standing on the tennis courts as they broke silence. Peter has no memory of this. He has been looking for this answer for more than 60 years. Time can distort memories. Trauma can, too.

"We all talked about it, the four of us. We all knew and that was a really good thing for us at the time, to be able to talk about it," Eldred said. "It wasn't right away that we all admitted to each other, confided in each other. I'm sure it'd been going on for a little while, privately, but at one point we all realized we were in the same boat. And so that was a good thing for us, to be able to talk about it among ourselves."

Eldred remembers liking Norman. Admiring him.

"I guess they call that grooming," he said.

Eldred said he and Norman never spoke of the abuse or of keeping secrets. He said there was likely an understanding between them, which Eldred gathered the courage to breach. Afterward, Eldred said there was relief, but something else, too: compassion for Norman, which sexual violence experts say can happen when survivors feel a sense of connection and care toward the person who is abusing them. Survivors of child sexual abuse are also often groomed to feel the abuse is their fault and responsibility, and because of this can struggle with the possibility of the person committing the abuse getting in trouble.

"I eventually told my brother ... and he told the director, and that's why I got pulled out of our cabin, which we were all in, one night, and brought down to the main house," Eldred said. "And the director asked me a bazillion questions about what happened. And I told him all the truth, and shortly thereafter Norm was called on. And I was sitting back in the director's office and I got to see Norm actually on the outside of the door. And he was just given his walking papers. ... They just said, 'You're gone. You're out of here.' ... My memory of that is how sad his face was. We all, on a lot of levels, really liked Norm. This obviously made it different, but for me, for whatever reason at the time, my memory of seeing Norm leave there wasn't: 'Oh God, thank God. Get out of here you monster.' It (was): 'Oh God, Norm. I'm so sorry it's come to this.'"

'I never forgot it. I'll never forget it.'

Eldred revealed the names of two other boys who shared their cabin and who he said Norman also abused. USA TODAY located one: Doug Clapp, a retired Maine judge.

On a Friday afternoon, Doug's wife, Judy, called, affable and eager, responding to a message about Camp Najerog.

Judy said Doug has Parkinson’s disease, which can make it difficult to understand him on the phone. She said she'd stay on and translate when necessary. They sat together in his study, listening as a reporter resurrected the past. Peter. Eldred. What they said of their abuse.

"I remember them," Doug said. "What do you want to know?"

"Well, she wants to know if you're aware of any of that," Judy said.

"Yeah, I'm aware of them, I'm aware of it," he said. "I guess you could say I was part of it."

A beat later, he explained.

"I was also abused," he said.

Doug said he could remember the counselor's name, but when he tried to say it, it escaped him. It’s then that Judy started asking her own questions. She asked if Doug's older brother knew. No. She asked if his mother knew. He thought so.

"I remember my father talking to me about it," he said. His dad tried to bring it up on the golf course, but Doug was embarrassed and brushed it off.

"You don't think you told them?" Judy asked.

"The camp would have told them," he said.

"Kid (Gore) may have told them," Judy clarified.

"You didn't tell your dad, no doubt," she said.

"No, I didn't," he said.

"You might have told your mom," she said.

"No, I didn't tell her either," Doug said. "I haven't really spoken – you didn't even know about it."

"This is the first I'm hearing of it," Judy said.

Judy doesn't sound shaken. She and Doug have been together for more than half a century. In her eyes, she said it changes nothing.

"We're crazy about each other," she said.

Judy began to process out loud.

"Doug has always praised the camp, and Kid Gore and what he learned there," she said. "We have two sons, and three grandsons, and they've all benefited from that independence that Kid gave those guys. I mean, he can tell stories and stories about things he did there, and what he learned."

Eldred expressed the same. To both these men, Camp Najerog remains a singular place.

"Norm Nicholson," Doug blurted out.

"Norm?" Judy asked.

"Nicholson," Doug said.

It hung there. A revenant.

Doug said Norman liked vulnerable kids. He remembers he had a girlfriend who he brought to camp once. Doug said Norman would abuse boys in their cabin, sometimes while other children slept. He'd conceal it under a blanket.

Doug doesn't remember a specific conversation with Eldred or Peter about the abuse, though he recalled it became an open secret. He said campers would tease Norman about his preference for young boys. After Norman was fired, Doug doesn't remember Gore ever talking to him about it. He and Eldred said they were never asked to speak to the police, but Doug said the town doctor came to the camp to talk to a group of them. It wasn’t productive. They were mortified, he remembered, and reluctant to speak.

For Doug, like Eldred, life moved on. Doug and Judy fell in love and married their senior year of college, then Doug attended law school at American University in Washington, D.C., and they had two boys. They moved to Maine, where Doug had a successful career in law and was appointed to the Maine District Court, where he presided for three terms until his retirement in June 2003. Judy retired from teaching then, too. They bought a yacht and for nine years sailed from New England to Trinidad and all islands in between, finally settling in St. Petersburg, Florida. They sold their boat a few years ago, after Doug's diagnosis.

“We’ve had a great life,” Judy said.

At one point while Judy was speaking, Doug interjected.

"I never forgot it," he said. "I'll never forget it."

"Does it affect us?" she asked.

"I hope not," he said with a laugh, defusing the enormity of the question.

"You don't think it does?" she pressed.

This time he didn't laugh.

"No," he said firmly.

"Yeah," she said. "That's interesting. Wow."

The psychology of pedophilia

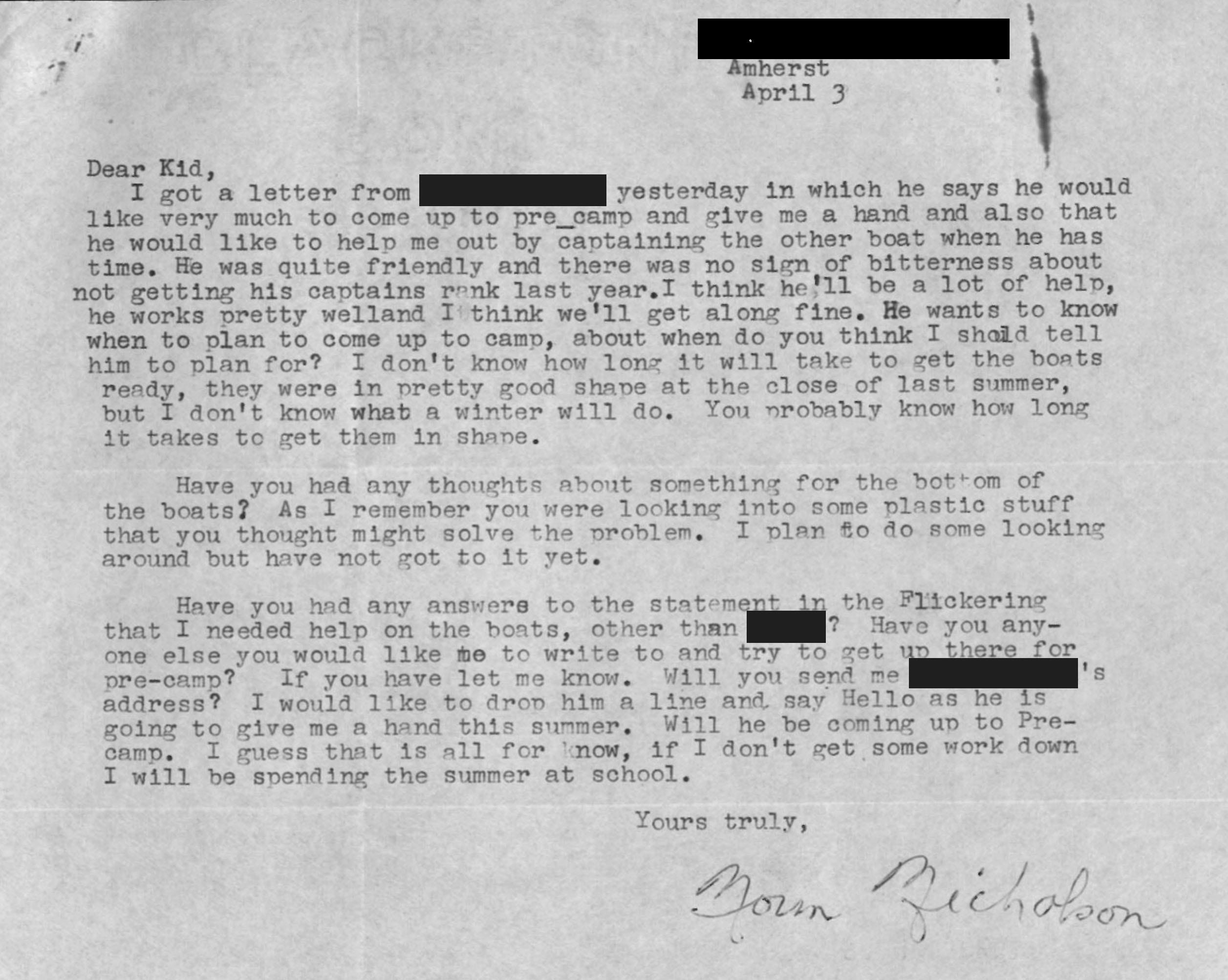

None of the people USA TODAY interviewed know what happened to Norman Nicholson after he was fired from Camp Najerog. USA TODAY looked through documents from the camp housed at the University of Vermont but did not find a record of Norman's firing.

Norman Kibby Nicholson is listed as a student in the 1958 University of Massachusetts Amherst yearbook. Peter, Eldred and Doug all say the yearbook photo is of their former counselor.

USA TODAY located a person of the same name whose birth year matches the one listed in Norman's profile in the University of Massachusetts yearbook. He denied working at Camp Najerog or knowing Peter Wien, Eldred French or Doug Clapp.

Peter, Eldred and Doug all refer to Norman as a pedophile. A pedophile is an adult who is sexually attracted to children. Scientists who study sexual disorders say evidence shows pedophilia is determined in the womb, though environmental factors may influence whether someone acts on an urge to abuse.

Pedophilia: Science suggests it isn’t a choice, but abuse is

“The evidence suggests it is inborn. It's neurological," said James Cantor, a clinical psychologist, sex researcher and former editor-in-chief of the journal "Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment.”

Pedophilia is often used as a synonym for child molestation, but experts say some pedophiles never hurt children, and some people who sexually abuse children are not pedophiles – they may molest kids because they are disinhibited, vengeful or afraid of adult sexual partners.

When a perpetrator has multiple victims, especially male victims, it is more strongly associated with “genuine” pedophilia, Cantor said.

Experts say pedophiles groom their victims and their environments to abuse without getting caught. Eldred remembers Norman as among the most trusted counselors.

“He was caring. He was in many ways a good moral compass. You couldn't make fun of other people – he would have corrected you if you tried to do that,” Eldred said. “He was very well thought of by administration and most all the campers. He was a great counselor.”

Some experts who study sexual disorders argue it's too difficult for pedophiles to access mental health care, especially when they fear being reported to authorities.

Anna Salter, a psychologist, author and internationally recognized expert who has done more than 500 evaluations of high-risk sex offenders, said that while pedophiles may not choose their sexual attractions, they are culpable for perpetrating harm.

"Pedophiles may not have control over the fact that they are attracted to kids, but they are responsible for whether they do or don't act on it," she said.

'We came out of the tunnel so differently'

Peter, Eldred and Doug all say Norman sexually abused them, and eventually, he was fired from the camp. But their memories diverge on which summer the abuse occurred, exactly how the camp responded and whether they confided in one another at the time. (Eldred remembers this vividly, Doug remembers this vaguely, and Peter doesn't remember this at all.)

Eldred and Doug's lives did not unfold like Peter's. They fell in love, married, raised children, had grandchildren. Both still remark on the camp fondly, separating Norman's abuse from experiences they saw as overwhelmingly positive. Eldred became a counselor at Camp Najerog. Doug still has a picture of the camp up in his house in Maine.

"I'm not sure what the difference (was) – how we came out of the tunnel so differently," Eldred said.

Trauma has no formula. It's not a neat equation. Many factors influenced the trajectory of these men's lives, including how many times they were abused, how long the abuse went on, how their bodies responded to violence, the families they were a part of, their mental health, their sense of worth and self, how people reacted when they did speak up or reach out.

There were significant differences in the length of the boys' abuse. Eldred and Doug said they were abused one summer. Peter said he was abused over multiple summers.

There were differences in the level of accountability and support. Eldred and Doug watched the camp respond to the abuse in ways that made them feel protected, and both had at least one supportive family member. Eldred confided in his older brother, who reported the abuse, and he saw the camp director immediately fire Norman. Doug remembers the town doctor trying to talk to them and remembers that his father reached out, even if it wasn't a conversation Doug was willing to have.

But Peter said he wasn't there the summer Norman was fired. He has no memory of Gore sending Norman away. He said no adults ever reached out to him, not to try to understand why he was begging to go to a military academy over an idyllic summer camp, not when Norman got caught, to see if perhaps Peter, who also had Norman as a counselor, had been a part of that abuse during Norman's summers at Najerog. When he was biting and suffering, Peter felt his family was oblivious to his cries for help, and when he did eventually disclose to his brother, he said he told him that the abuse never happened and that he was hallucinating. When he finally told his mother, he was a grown man. He could see her descending into guilt, looking inward, rather than at her son. He could sense decades later that she still didn't want to look. Didn't want to see.

All of these moments, the subtle and profound, likely influenced the ways in which Peter, Eldred and Doug reacted to the abuse, and experts who counsel victims of sexual violence say all of those reactions are valid.

"People often talk about trauma as being an abnormal experience. So what's a normal reaction? And the answer is everything – everything that a trauma survivor tells you is a normal reaction," said Sharon Imperato, a counselor and trainer with the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center who has worked with survivors of sexual trauma for two decades.

Many men who've experienced sexual abuse face challenges in healing and seeking help because of the cultural commentary around masculinity. Sexual violence against men can make them feel as though they are no longer men. Men are viewed as strong, sexual, aggressive, stoic, protectors. Victims are mistakenly viewed as vulnerable and weak. Many men don't want to identify with that stereotype. They hide their abuse or deny it. They may disclose but minimize its impact. They may express anger because that's culturally acceptable, but not outright pain.

Psychologists: Aspects of 'traditional masculinity' harmful

Experts in sexual violence say they suspect more men are abused than statistics show. For numbers to be accurate, men who have been harmed have to identify what was done to them as being sexual violence, but if they're taught they cannot be victims, they cannot name their abuse.

Jim Struve, a licensed clinical social worker and executive director of MenHealing, which provides services and support to men who have been sexually assaulted or abused, said male survivors of sexual abuse often get caught in extremes. Many become overachievers – they try to do more, earn more, accumulate more. Others underfunction – they fail in relationships and at work, get in trouble with alcohol, drugs and the law.

"If they're on the extreme where they're really successful or high-functioning, it's like, looks like you've done fine, everything is OK, it didn't bother you, it didn't hurt you," he said. "If you're on the other extreme, people are getting in trouble ... but nobody ever asks, 'What happened to you?' Instead, the issue is 'What's wrong with you?'"

Eldred became a state senator. Doug became a judge. Peter was fired from nearly every job he ever had.

Peter worked at a newspaper in Boulder, Colorado, an advertising firm and a psychiatric hospital. He was a stock clerk at Walgreens, a chauffeur, a bartender, a network marketer, a travel writer, a wild-animal rehabilitator and a tai chi instructor. Peter said his mother left him an inheritance, which has kept him afloat. He lives in the apartment his family bought when they moved to Denver.

One of Peter’s most successful ventures was as a councilman in the city of Norwalk, Connecticut, where he lived for several years before returning to Denver. While serving, Peter tried to block the Boy Scouts from obtaining a permit to use a city park for an event. He was against the organization's former policy on gay members and wary of reports that Boy Scouts were being abused.

Big winners in the Boy Scouts bankruptcy: Attorneys, who could walk away with $1 billion

"I couldn't hold a freaking job to save my life, but I got elected as a councilman because I was so vehemently into protecting people," he said.

Poindexter, the psychotherapist who specializes in trauma, said survivors of sexual abuse can struggle with situations that make them feel a loss of power or control. Peter said he suspects he failed in his career because he was resistant to authority, to ever feeling controlled again.

Among the most notable distinctions between Peter and Eldred and Doug is that Eldred and Doug don't blame the camp for what happened and don't find fault in its response. They blame Norman.

Peter said that if the camp didn't report Norman to the police, their response wasn't good enough.

It's not known whether Gore or any parents reported Norman to the authorities, though none of the victims USA TODAY spoke with were interviewed by local law enforcement. The Wilmington Police Department does not have any police reports naming Norman Nicholson but said its records don’t stretch back to the '50s. USA TODAY spoke with one of Gore's grandsons, Chris Gore, who attended the camp for several years in the 1950s and 1960s. Chris said he does not remember Norman, though he was careful to say he has only faint memories of even his own counselors. He said he was never told of any abuse at camp and therefore has no knowledge of whether Norman was ever reported to police.

Salter, an expert on high-risk sex offenders, said if the camp didn't go to the police, then it "didn't do enough, but the camp was way ahead of its time in what it did do."

"If they'd fired him and contacted at least some of the families, they did more than 99% of places would have done at the time," she said. "In the '50s, they were still blaming children for child molestation."

Today, states have laws that require certain people to report known or suspected instances of child abuse and neglect. In Vermont, physicians and camp owners are required to report child maltreatment. The state's Department for Children and Family Services said these laws were not on the books in the 1950s.

When Peter was a boy, he was too afraid to tell the adults in his life about the abuse. But when Norman's perpetration was discovered, he wishes at least one adult would have asked, "Did Norman hurt you, too?"

'Why is the public not outraged?'

Peter started opening up about his abuse in his late 20s, to friends and to therapists, though finding good care has been difficult. Sometimes he couldn't afford it; other times he couldn't connect with the clinician.

Peter was eventually diagnosed with suicidal depression and a mild dissociative identity disorder, which can occur among survivors of sexual abuse. It happens when a situation is so horrible that a person has to disassociate to survive it. They leave the scene, become somebody else. Dissociative disorders can create problems with “memory, identity, emotion, perception, behavior and sense of self,” according to the American Psychiatric Association.

Nora Gluck is a licensed clinical social worker who treated Peter about half a decade ago in her practice in Trumbull, Connecticut. Peter gave Gluck permission to speak with USA TODAY. Gluck said she and Peter worked together for less than a year. Peter was a challenging client. She said she could tell right away that Peter's issues were severe.

"One time he came in and he was lying on the floor, and he said he needed a blanket. He was shaking so much. So I brought him a blanket. It was a difficult, difficult situation to deal with."

Gluck said it was obvious Peter was traumatized by the sexual abuse, but his family's reactions to his turmoil compounded the harm. Peter trusted Norman, and he hurt him. Peter trusted his parents and his brother, and he felt they didn't help him.

Peter's parents are deceased, and his brother declined to speak with USA TODAY.

Gluck said she sensed Peter never really trusted her, which made it almost impossible to work with him. Loss of trust is a core issue for survivors of childhood sexual abuse.

"He was just, well, not like most of the patients I see who come in and tell you a story and come in the next time and tell you more of the story," she said. "He never developed a normal therapy relationship, which would be trusting the person and liking the person. ... I think he was someone who was so deeply traumatized that I couldn't work with him. I wouldn't call it – no, it's not anger. It's rage."

MenHealing's Struve said part of why survivors carry that rage is because from the Catholic Church to Penn State to the Boy Scouts of America, sexual violence is still all around them.

"Why is the public not outraged about that?" he asked. "Why do ... survivors have to be the ones who are outraged?"

'Caught in the shadows'

When Peter learned what Eldred and Doug disclosed, he was stunned and affirmed.

"Wow," he said quietly, before unleashing a rare laugh.

When Eldred and Doug learned what Peter had endured, they were shocked and anguished.

"I am truly sorry that the abuse has caused Pete so much pain," Doug wrote in an email. "Please let him know that I do care."

Peter has wanted to tell his story for a long time, and he'll be the first to admit that he has been a bit obsessed with telling it. He has wanted so much to be believed.

When USA TODAY reached Gore's grandson, Chris, he said his family is protective of Najerog – it's not just a camp his grandfather founded, it's a family legacy – but that reverence for his grandfather doesn't invalidate what happened to Peter. Chris said it was good Peter's story would see light.

"He was someone I admired just nonstop," Chris said of his grandfather, and at the same time he suspects "there's a lot of people that are going to relate to (Peter's) story. ... It's going to be very valuable."

That's Peter's hope. He wants people to know there are men like him who were hurt – in their homes, their camps, their churches, their locker rooms – and still are.

Peter reflects often on the things in his life that might have gone differently if not for those summers. He might have been a professional photographer. He loves to take photos – cracks in the pavement, fallen branches, the things we see every day but fail to notice. Or a writer. His writing is elaborate and descriptive, full of detail and observation. He might have been a dad. The abuse has devoured many possibilities.

But he also may have still been troubled, maybe less troubled, maybe a different set of troubles. There's no knowing.

In the final weeks of interviewing, Peter began to wonder where forgiveness fit in his story. Vindication shifted to ambivalence. He tried to imagine what it might feel like to be Norman, to have a 65-year-old secret unearthed in ways that could ripple across his own life. He felt empathy for Norman, and for himself.

"I'm sitting here going ... 'Peter, you have really suffered a lot, and you don't really need to. You didn't do anything wrong, but you got caught in the shadows for a really, really, really long time," he said. "You don't need to blame anybody, you don't need to punish yourself anymore. You just need to get out of the shadows."

Peter said this on an autumn afternoon before heading to therapy across town. Earlier that day, he looked at a picture of himself from the camp – small, slight, shirtless, bottle-feeding a baby goat. He was skin and bones and potential and hope. He struggled to recognize himself. He was just a boy.

Peter is not alone. If you've had an experience like Peter's and want to share your story, email adastagir@usatoday.com.

If you are a survivor of sexual assault, RAINN offers support through the National Sexual Assault Hotline (800.656.HOPE and online.rainn.org).

MenHealing provides resources and services for adult males who have been sexually victimized during childhood or as adults. You can visit their website for more information (menhealing.org) or follow MenHealing on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.

The Boston Area Rape Crisis Center provides free, confidential support and services to survivors of sexual violence ages 12 and up and to their families and friends. Visit their website at barcc.org, call their 24/7 hotline at 800-841-8371 or chat online from 9:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m. at barcc.org/chat.