No one sets out to be a Black Lives Matter martyr. But somewhere along the way last year, as masked marchers from Louisville to Las Vegas chanted her name, Breonna Taylor became a symbol of change.

Taylor’s fate was sealed in the wee hours of March 13, 2020, when Louisville Metro Police officers burst into the 26-year-old’s apartment on a no-knock warrant, firing 32 bullet rounds and killing the emergency room technician as she stood in her hallway with her boyfriend, who survived.

Now her death is bringing new life to the stories of other Black women who have died at the hands of police or in police custody, those whose names and identities have largely gone unknown and unacknowledged.

While the names of too many Black men and boys killed by police – Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice – are widely known, Black women’s cases have rarely garnered national attention.

A notable exception is Sandra Bland. In 2015, the Illinois native was found hanged in a Waller County, Texas, jail a few days after a traffic stop by a state trooper, captured on video, ended with her arrest. Her death was ruled a suicide, something her family has publicly disputed.

There’s not a lot of data on the police-involved deaths of Black women; no national registry exists. But The Washington Post has noted nearly 250 women, including 48 Black women, have been shot and killed by police since the newspaper began tracking police-involved shootings in 2015.

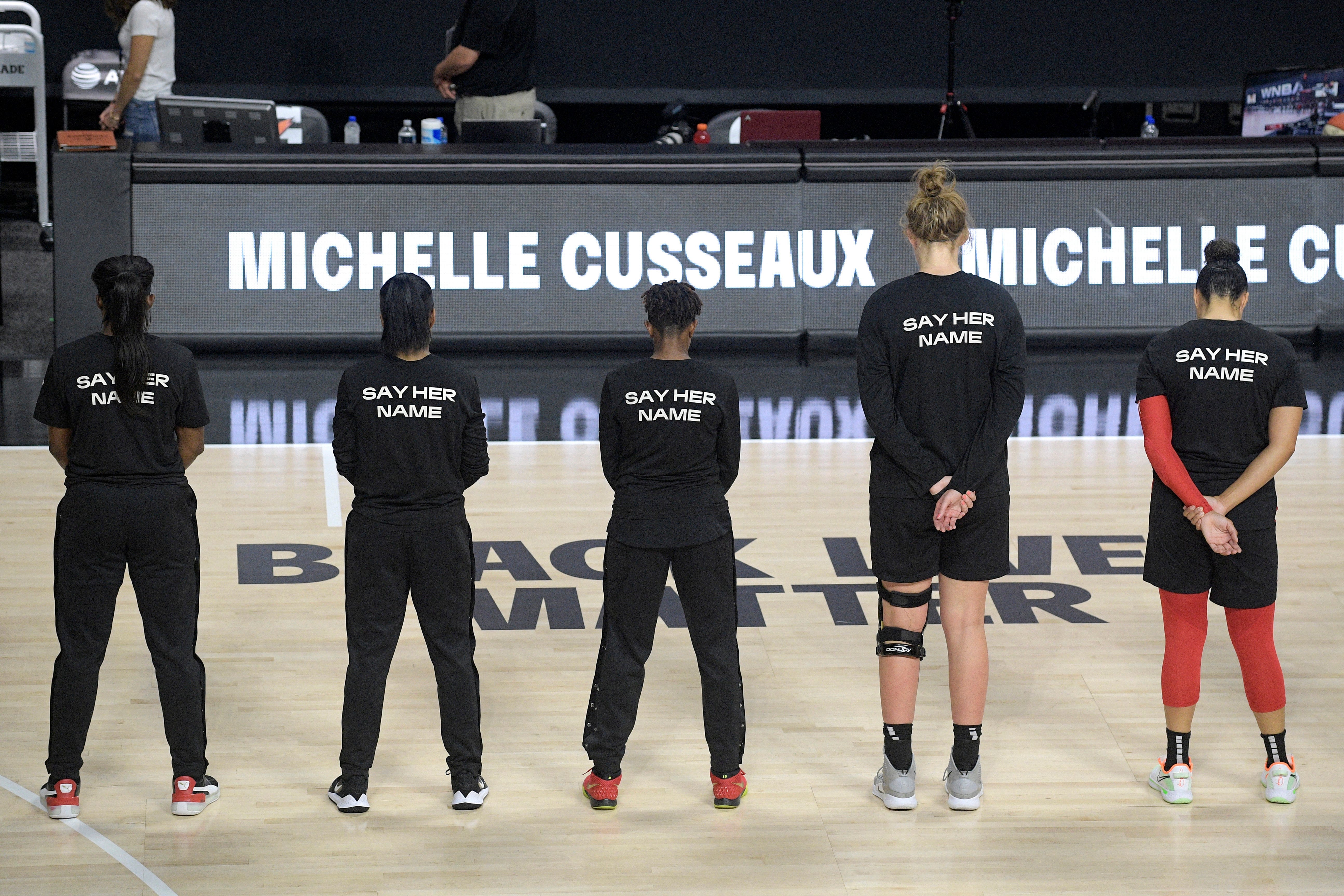

It was the death of 50-year-old Michelle Cusseaux in 2014, not long after the police shooting of Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, that drew the attention of the African American Policy Forum.

Police in Phoenix were sent to Cusseaux's house for a mental wellness check. She answered the door while holding a hammer in one hand; police shot her through the heart. Her mother, Fran Garrett, marched with her daughter’s casket through downtown Phoenix weeks after her death, calling for an outside agency to investigate the shooting.

This was the catalyst for the #SayHerName campaign.

The start of a movement

“Black girls as young as 7 and Black women in their 90s have been killed by the police, and for a long time nobody was talking about it,” said Kimberlé Crenshaw, co-founder and executive director of the African American Policy Forum (AAPF) and creator of the #SayHerName campaign. “Anti-Black racism is experienced in gendered ways. Elevating this message is important to give a holistic view and expose that Black women and girls are not exempt from abusive policing practices.”

A professor of law at UCLA and Columbia Law School, Crenshaw, 61, is a leading authority on Black feminist legal theory, race and civil rights who developed such terms as “intersectionality” and “critical race theory, ” which examine the systems at play that perpetuate racism.

Wearing a white hoodie with the names of Black daughters, sisters, wives, cousins and community members killed by police, she explained the origins of #SayHerName during a Zoom interview.

Back in 2014, AAPF and the Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies (CISPS) at Columbia launched the campaign to bring awareness to often forgotten or invisible victims and give their families support.

The following May, “we hosted the first #SayHerName vigil in New York’s Union Square,” she said. Relatives of at least 16 Black women killed by police assembled from around the country.

Soon after, AAPF and CISPS released a groundbreaking report: “Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women.” Co-written by Crenshaw and Andrea J. Ritchie, a lawyer and activist, it outlined the objectives of the movement, providing an intersectional framework for understanding Black women's susceptibility to police brutality and state-sanctioned violence.

“There is an impact in a community in feeling terrorized. The goal of terrorism is to not just harm individuals but put terror in the hearts of a whole community, and that is what police violence like the kind Breonna Taylor experienced does,” said Ritchie, author of “Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color.” Ritchie, who works independently from AAPF, spoke recently with The (Bergen County, N.J.) Record, part of the USA TODAY Network.

“And of course the community has risen up in resistance and said, 'We are not accepting this; we are not going to be terrorized.' But the reality is, that is the impact.”

The grief of the mothers

Historians say Black women have long been terrorized – raped, beaten, worked to the bone – since the first enslaved Africans arrived in the British colony of Virginia in 1619.

“There have always been untold and undocumented stories of violence against Black women and girls,” said Karsonya Wise Whitehead, associate professor of African and African American Studies at Loyola University Maryland.

Some incidents foreshadowed the public outrage seen today. Whitehead cited the 1984 case of Eleanor Bumpurs, 66, an elderly disabled Black woman gunned down by New York police as authorities tried to evict her from public housing. The back rent she owed was less than $100.

“It reminds us of the challenges associated with being Black and being a woman in this country. ... We need the space to say their names, push this hashtag forward into our daily lexicon, and remind people that the violence against our people does not stop at the gender divide," Whitehead said.

The #SayHerName campaign, which is largely funded by philanthropic partners, focuses on direct advocacy. For instance, Crenshaw hosts an annual #SayHerName Mothers Weekend, bringing together mothers who have lost daughters to police violence for dialogue, dinners and pampering.

The organization works to meet the specific needs of each family, even providing temporary housing and financial stipends if necessary. Most important, it’s a safe space where the mothers can construct a community of support – whether they need empathy or information on how to mobilize and advocate for racial justice.

“I am the mother of a beautiful Black woman whose life was snuffed out by the police,” said Gina Best, an Iowa native who lives near Washington, D.C. “There is no pill I can take to alleviate the pain.”

Best's daughter India Kager, a 27-year-old Navy veteran, postal worker and mother of two, was killed in September 2015 by a Virginia Beach SWAT team as she sat in a car at a 7-Eleven with the father of her 4-month-old baby boy. The child was in the back seat.

Best filed a wrongful death lawsuit, and in 2018, a jury ruled two of the officers were responsible. The award was $800,000 to Kager's minor children.

“Rage propels me forward,” said Best, who noted that there are police officers in her family. “I modulate my grief in order to reclaim the narrative of the life of my daughter. I don’t care to forgive the men who did this. They have wreaked havoc, destruction and pain.”

The mothers have become, as Crenshaw put it, “a sisterhood of sorrow.” They regularly text, call and visit one another.

Korryn Gaines, 23, was riddled with bullets in her Baltimore County home in August 2016; the gunfire also seriously injured her 5-year-old son. Police had shown up to serve a failure-to-appear warrant from a traffic violation. An hours-long standoff ensued with Gaines, who was armed with a shotgun, filming on her cellphone and posting live on social media.

“The one word to describe how I feel is ‘broken,’ ” said her mother, Rhanda Dormeus. “Since her death, my family has been in turmoil. Alcohol abuse, anger issues, the emotional trauma has been so profound. As the matriarch I must be there for everyone. At 4 a.m. my daughter was screaming, crawling on the floor, crying, saying she wished it would have been her instead of her sister.”

In 2018, a jury awarded Gaines' family $37 million in a wrongful death lawsuit. The verdict was overturned by a judge in 2019 but later reinstated by a higher court.

“The will of the people was done,” said family attorney J. Wyndal Gordon of the jury’s original verdict. “Now the county needs to show some accountability and financial responsibility for the harm (police) caused this family for generations to come.”

The Fraternal Order of Police, with more than 350,000 members, is the nation's largest law enforcement labor organization. After the death of George Floyd in 2020, national president Patrick Yoes released a statement saying in part: "... police officers should at all times render aid to those who need it. Police officers need to treat all of our citizens with respect and understanding and should be held to the very highest standards for their conduct."

Accountability and hope

Congress has taken up police accountability. On March 3, the House of Representatives passed the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2021.

The bill is intended to hold police accountable, change the culture of law enforcement and empower communities. It also seeks to build trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve by addressing systemic racism and bias to help save lives.

“Black communities have suffered from police abuse for as long as we’ve been here,” said Rep. Karen Bass, D-Calif., who introduced the measure. “None of us are safe if essentially law enforcement can treat us any way they choose.”

Chanelle Helm is a Black Lives Matter Louisville organizer who has led demonstrations in the city since last May, when Taylor’s case became national news.

“Very intense protests took place. That very first night, police used tear gas on us. They were shooting pepper-bomb bullets,” Helm said. “Someone was murdered by the state, in a pandemic while people were fearful, losing their homes. The disrespect. We have been saying Breonna’s name ever since and trying to get justice.”

None of the three officers involved were charged with her death. One was indicted on a charge of wanton endangerment and has pleaded not guilty. Two have been terminated.

Taylor’s devastated family keeps her legacy alive. Crenshaw has reached out to Taylor's mother, Tamika Parker, in the past year to connect her with other grieving mothers.

Taylor's younger sister, Ju’Niyah Palmer, is a college student who was sharing the apartment with Taylor when she was killed. She remembers fun, simple memories: doing cartwheels with her sibling; going to the car wash. She feels Taylor's presence. “Like, I really do.”

Yet despite her grief and pain, there is hope. “When I see the images of (Taylor) and people painting images of her, it makes me feel joyful because it makes me feel like people are still thinking about her,” she said.

Indeed, the world is thinking about Breonna Taylor and saying her name. And perhaps they will now whisper, shout and speak the names of other Black women, too.

Contributing: Shaylah Brown, The (Bergen County, N.J.) Record