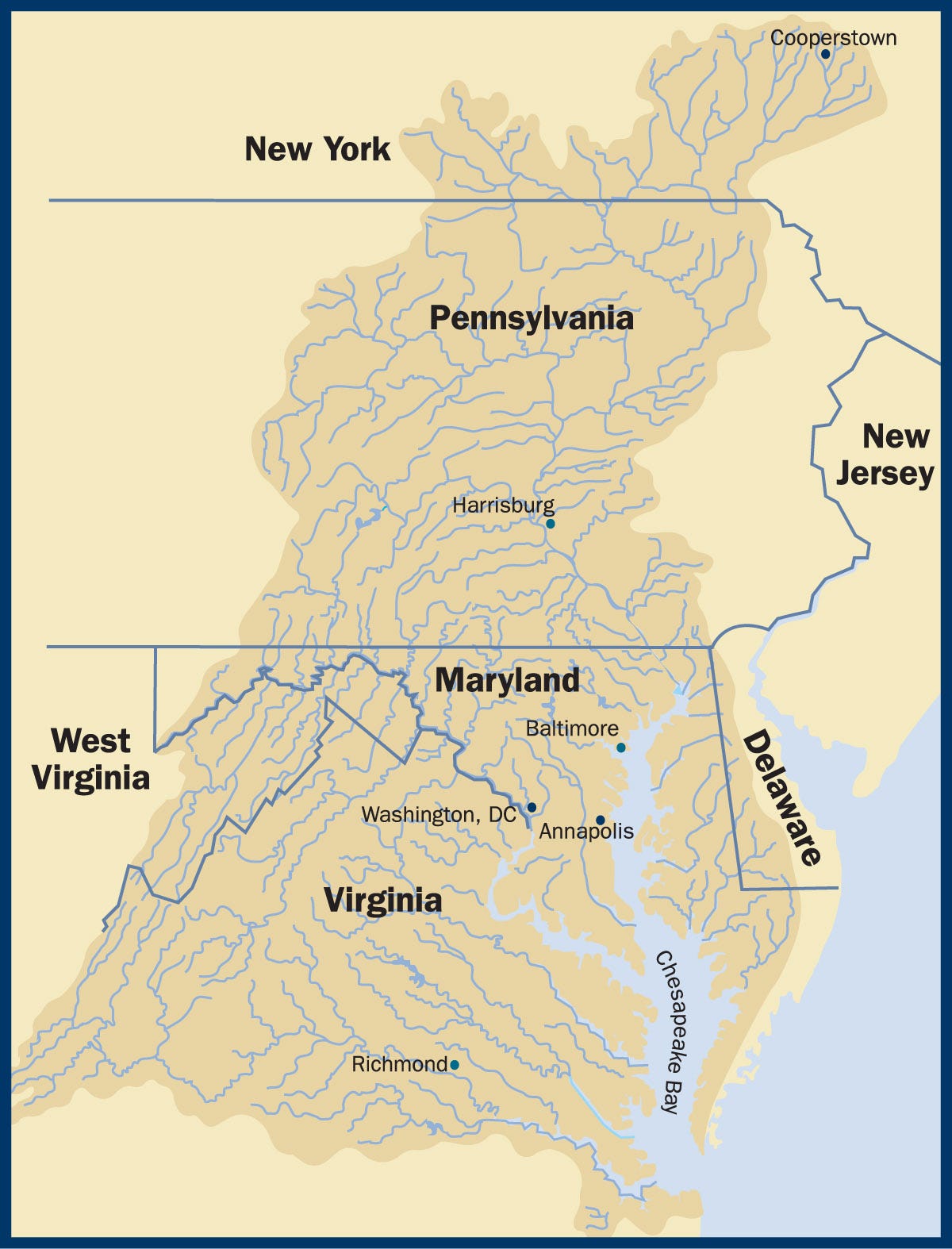

Last, best chance for restoration: Pennsylvania is $324 million behind in its commitment to clean up the Susquehanna and Chesapeake watersheds.

This USA Today Network special report explores solutions to deep threats that flow through New York, Pennsylvania and Maryland as the Susquehanna River feeds the Chesapeake Bay — with life and death.

In the best of times, it’s a hard sell.

When things were normal, it was difficult to convince colleagues and his constituents that money spent on saving the bay was worthwhile, said Pennsylvania state Sen. Gene Yaw, R-Williamsport.

“The bay’s a hundred miles away,” they would say. “Why should we care?”

There are many reasons why people should care, and Yaw, who chaired the Chesapeake Bay Commission in 2020, would recite them to skeptics — the watershed affects health and economics and just about everything. It provides drinking water. It is essential to the overall health of the environment. The Chesapeake Bay and the Susquehanna River are engines of economic activity.

Still, it was always a hard sell.

And that was during normal times.

With the COVID-19 pandemic depleting state budgets and dominating political discourse, these are not normal times.

A blueprint for clean water

The plan to save the bay is called the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint, touted by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation as “the best, and perhaps last, chance for restoration” of the watershed.

It dates to 2010, when the bay foundation and the states of Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia and others settled a lawsuit with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The settlement included a provision setting what was called a total maximum daily load, which, according to the foundation, “provides science-based, enforceable limits on the amount of pollution entering the Chesapeake in order to remove the bay from the federal ‘dirty waters’ list.”

REPORT: Rock-bottom rockfish numbers drag down Chesapeake Bay health score

As a result, six states and the District of Columbia agreed to a blueprint to develop individual plans to achieve those limits by 2025. The EPA, for its part, “committed to holding them accountable and imposing consequences for failure if necessary,” according to the foundation.

Of the six states, Pennsylvania and, to a lesser extent, New York have failed to meet their commitments. Pennsylvania is considered the worst offender, as the state has fallen well short of meeting the standards set in the blueprint.

It all comes down to money.

More: 8 simple things YOU can do to restore the Susquehanna River and save the Chesapeake Bay

Pennsylvania is failing the bay

In 1608, Captain John Smith set out from Jamestown to explore the Chesapeake Bay. He found pristine water teeming with wildlife, writing in his journal that oysters “lay thick as stones." Their beds were so dense that they provided a hazard to navigation.

As European colonists began to settle around the bay, developing along its shores, the Chesapeake’s health began to decline. Development and agriculture throughout the Susquehanna watershed resulted in huge increases of pollutants pouring into the bay.

During the last century, oyster populations were decimated.

The first attempt to clean up the bay occurred in 1983 when states in the bay’s watershed signed an agreement to work together to reduce the toxins.

That agreement failed. Other agreements followed. While some progress was made, they also failed.

When the blueprint was adopted in 2014, it was believed that having federal enforcement was key to making it work.

And while the blueprint has had some success, it is also in danger of failing — mostly because of Pennsylvania.

"If Pennsylvania does not meet its goals by 2025," bay foundation president Will Baker said during a January news conference unveiling the foundation's 2020 report card on the bay, "there is no doubt that the Chesapeake Bay will never be saved."

Clean river and bay are economic benefits

Those advocating for cleaning up the bay — a group that includes legislators, state attorneys general and environmentalists — say it shouldn’t be that difficult to convince the legislature to allocate more money to clean up the Susquehanna and Chesapeake watersheds.

For one thing, it would seem to be required by the Pennsylvania constitution, enshrined in Section 27 of Article 1, which states, “The people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment.” Pennsylvania is one of only 11 states that recognizes clean air and water as a basic civil right.

For another, the economic impact is enormous. Before the states adopted the blueprint, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation estimated that the bay contributed $107 billion a year to the economy.

If the so-called blueprint to reduce contamination of the bay is not followed and fisheries and the businesses supported by them suffer, that could drop by $5.6 billion. If the blueprint’s goals are achieved by 2025, resulting in larger harvests of seafood and increased business opportunities in the watershed, the study concluded, the economic benefit would increase by $22.5 billion annually.

More: Total Maximum Daily Load: A pollution diet for the Chesapeake Bay

Each of the states in the watershed would also benefit. Pennsylvania's economy, for instance, would see an increase of more than $6.2 billion annually from businesses involved in aquaculture and recreation, according to the bay foundation’s study.

But Pennsylvania has a checkered history when it comes to spending the money needed to restore the Susquehanna watershed. In 1999, the state’s Department of Environmental Protection started the Growing Greener Program, creating a standing fund to pay for watershed restoration projects. In its first three years, the program funded 1,100 projects totaling $333 million. But since the mid-2000s, the amount of money allocated to the fund has dropped dramatically, from an average of $200 million in the 2005 to about $60 million in 2016.

Former governors and the state Legislature saw the Growing Greener fund as a kind of all-purpose piggy bank. David Hess, who as DEP secretary under former Republican Gov. Tom Ridge helped create the fund, told the bay foundation’s B.J. Small that since 1999 the fund “has seen chunks of funding lopped off” and used for “unrelated things, including a parking garage in Scranton and energy projects.”

Hess said, “The General Assembly and various governors, Republican and Democrat, since 1999 have been playing a shell game with these different funds. They aren’t adding new money to the pot.”

COVID-19 pandemic complicates problem

This year’s state budget offers little hope that Pennsylvania can live up to its commitment to the bay, a commitment that would require spending $324 million a year on watershed improvement projects.

The state is looking at a budget deficit in the neighborhood of $5 billion caused by the economic downturn brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The question is, where are we going to get $324 million a year,” Yaw said. “It was very hard to find it before, and now all of our efforts took a back seat to the pandemic.

“It’s hard to get people to care about the environment when they don’t know if they’ll have a job or be able to put food on the table. Right now, people are more worried about how they’re going to pay their bills than the bay.”

More: 5 things government leaders can do to save the Susquehanna River and the Chesapeake Bay

Pennsylvania looking for money under couch cushions

The best case scenario is that Pennsylvania’s budget will remain static. And that's what Gov. Tom Wolf has proposed in the state's 2021 budget, a “flat-funded” budget that is essentially a spending freeze.

Yet others, most notably state House Speaker Bryan Cutler, a Lancaster County Republican whose district includes the Susquehanna from Columbia to the Mason-Dixon Line, had advocated taking money from what are called “dedicated funds” to balance the budget. Among those funds is the Environmental Stewardship Fund, Growing Greener and others established for environmental protection. (In January, the state Department of Environmental Protection announced $1 million in grants from the stewardship fund to 26 counties to mitigate pollution.

Speaking on WITF-FM's "Smart Talk," Cutler said, “The analogy I would use is that’s kind of, you know, that’s taking your change jars and checking under the couch cushions in your home before you ever ask the taxpayers pay more.”

Raiding those funds, the bay foundation asserts, would put Pennsylvania even further behind on its commitment to the bay. Noting that reducing pollution has economic and public health benefits, Shannon Gority, the bay foundation’s Pennsylvania executive director, recently wrote that the state “cannot afford to backslide any further.”

Biden administration could help

Baker, the bay foundation’s president, believes help may be on the way.

The election of President Joe Biden should be good for the bay and the efforts to clean it up. For one, he believes a Biden administration would reverse the rollbacks in clean water regulations and funding cuts proposed by the Trump administration. For the 2021 federal budget, the Trump administration had proposed cutting funding for the Chesapeake Bay Program by 91 percent, from $85 million to $7.3 million. Congress resisted the cut and instead, increased funding for the program by $2.5 million.

Baker believes that Biden’s EPA, led by North Carolina's environmental quality secretary, Michael Regan, will be more interested in enforcing the blueprint and assisting states to meet its requirements by providing money and technical help.

"The funding gap does not need to be met exclusively by Pennsylvania," Baker said during a news conference in January, saying that the state could work with the federal government to obtain funding to meet its goals.

When Regan's appointment was proposed, Baker said, "The Trump EPA has undermined the restoration effort by dismantling key air and water protections and allowing some states to shirk their responsibilities. ...We are confident that with Michael Regan at the helm, EPA will recommit itself to being the strong federal partner we need to save this national treasure.”

Baker said, “It’s also helps that President Biden comes from a Chesapeake Bay state. We expect that he will have a personal interest in the bay.”

Baker's faith in Biden was rewarded nearly immediately. Upon taking office Jan. 20, Biden signed a number of executive orders overturning Trump-issued orders that rolled back environmental regulations.

He also believes Biden’s election bodes well for settling the lawsuit filed in September by the foundation, the Maryland Watermen’s Association, Maryland, Virginia and Delaware and the District of Columbia, among others, against the EPA for violating the Clean Water Act by not forcing Pennsylvania and New York to live up to its commitment to the bay.

And he believes that once the pandemic ends, the effort to save the bay will be back on track.

“We’re going to get to a point where COVID-19 is in the rear-view mirror,” Baker said. “My father was a child during the 1918 flu epidemic, and his father was a country doctor. He said it was horrible, but we survived it as a society. We’ll survive this.”

And then, he said, we can get back to work to clean up the bay.

“I’m a hopeless optimist,” Baker said. “We can do this.”

Columnist/reporter Mike Argento has been a Daily Record staffer since 1982. Reach him at 717-771-2046 or at mike@ydr.com.