Experts are thrilled about the reported safety and effectiveness of two COVID-19 vaccines rolling out across the country. But they remain concerned about what still could go wrong to shake the public's fragile faith in it.

Nearly everything about the process has gone well so far, shepherded by the Trump administration's Operation Warp Speed.

The first two vaccines, one from Pfizer-BioNTech and the other from Moderna, were ready well before anyone expected. Trials showed them to be among the most effective vaccines ever, particularly for a notoriously hard-to-prevent respiratory virus.

And the initial days of the rollout, while far from perfect, have already led to 1 million vaccinations in the U.S., mostly among front-line health care workers.

Federal officials expect 20 million doses to be manufactured and available for shipping by early January, an additional 30 million doses by the end of that month, and 50 million more by the end of February.

Vaccines should become available for the general public as soon as late February or early March, according to Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar.

In interviews with USA TODAY over the past several days, a dozen vaccine experts were more guarded. Most believe vaccines won't become widely available until late spring or early summer, assuming no production problems and the authorization of two additional vaccines by sometime in February.

The federal government should underpromise and overdeliver, advised panel member Dr. Kelly Moore, associate director of immunization education at the Immunization Action Coalition, a nonprofit that distributes information about vaccines and the diseases they prevent.

"Projecting concrete dates that we cannot know risks setting the public up for needless frustration and disappointment," she said.

The panel members' concerns mainly revolve around what will happen before vaccines are widely available.

They worry the public could lose faith in the vaccine because of more allergic reactions like those already seen a few times or some other symptom – whether it's actually linked to the vaccine or not.

And they're concerned about potential glitches in distribution or any of the thousands of other things that could go awry with such a complex scientific, logistical and political process.

"Areas of particular concern," Moore said, "include unpredictable supply issues, storage and handling failures resulting in vaccine waste, and all sorts of data management and data sharing challenges resulting from the use of several new IT systems."

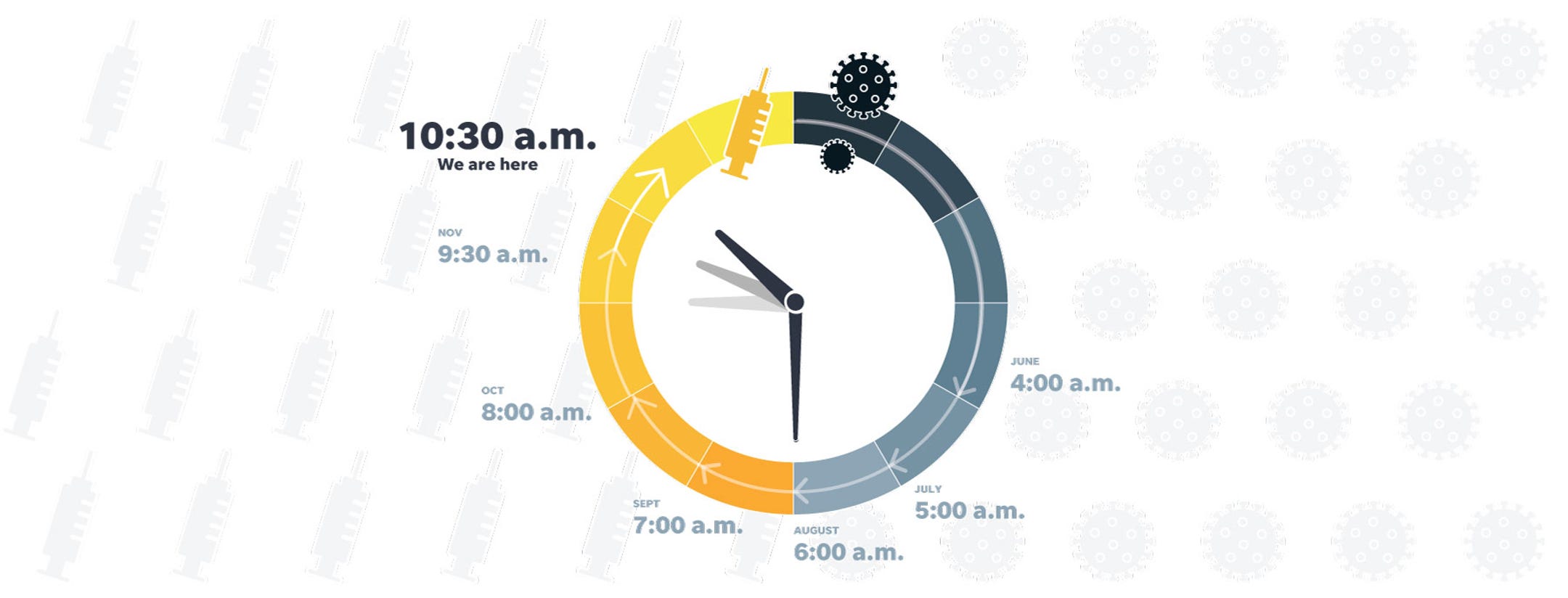

Every month, members of USA TODAY's expert panel gauge the progress of COVID-19 vaccines by choosing the time on an imaginary clock that began at midnight with the discovery of the virus in early 2020 and ends at noon, when a vaccine is freely available across the U.S. Each month, we calculate the median time – the midpoint of their estimates.

In June, that was 4 a.m. By October, the sun had risen and their consensus fell at 8 a.m. The time for November shot ahead to 9:30 a.m. – the biggest advance in a month to that point. For December, the panel returned to its steady pace and advanced the clock one hour to 10:30 a.m.

So far, so good

Overall, panelists said they're impressed with the development and manufacturing of the first two authorized vaccines.

"Manufacturing has been managed remarkably well," said Prashant Yadav, a medical supply chain expert and senior fellow with the Center for Global Development, an international development think tank based in Washington, D.C., and London.

Typically with a fast scale-up, "we usually have more hiccups," Yadav said.

Concerns have turned out to be overblown about maintaining the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine at the necessary supercold temperature, said Prakash Nagarkatti, vice president for research at the University of South Carolina in Columbia.

Several panel members said they were pleasantly surprised both vaccines appear safe – with no major, long-term problems – and are more than 94% effective.

"I was worried that the vaccine(s) would not be this effective but was thrilled with the results," said Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease researcher at the University of California, San Francisco.

"This is amazing and very impressive," said Pamela Bjorkman, a structural biologist at the California Institute of Technology. "I was worried about serious side effects from vaccinations, but there appears to be little to no evidence of this so far."

Sleepless nights to come?

Many of the panelists said they're still worried something will go wrong, causing the public to lose trust in the vaccine.

Right now, the biggest concerns are allergic reactions, which are rare but seem to be occurring more frequently than they should be, and a handful of cases of Bell's palsy, a neurological condition affecting muscles on one side of the face.

It's usually temporary, but Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, frets that more cases may drive people away from getting vaccinated.

"I'd like to see that not be a big problem," he said.

Sometimes, relatively rare events like Bell's palsy crop up more often than they should purely by chance. If you flipped a coin as many times as there were people in both vaccine trials, you could end up with heads five times in a row, he noted. "That's the tyranny of small numbers in large databases."

Offit, who is eager to get the vaccine himself in the next week or two, said he was concerned recently when he met a phlebotomist who won't take the vaccine because he's convinced that Black Americans such as him will get a different vaccine from white Americans – though of course that's not true.

"What worries all of us is that there would be a serious adverse event that was permanent," Offit said. "Then people would recalculate whether they think it's worth getting the vaccine."

Even if a side effect is extraordinarily rare and the likelihood of being infected with COVID-19 remains quite high, people may turn away from the vaccine, he said.

"Statistically, they're probably still so much better off getting the vaccine, because this is a common virus, a virus which even if it doesn't kill you can cause permanent harm," he said. "But people don't view risk that way," and people may conclude – against scientific evidence – that the danger posed by the vaccine outweighs that of the virus.

Among the panelists' other worries: There's plenty of time for serious production problems. Rich people could try to jump the line. And one scenario is out of anyone's control: The virus could mutate to make the vaccines less effective.

The risk of mutation "increases the longer we let millions of people continue to get infected and transmit the virus from one to another," said Dr. Gregory Poland, director of the Mayo Clinic's Vaccine Research Group and editor-in-chief of the journal Vaccine.

Still more to do on public messaging

Still more panelists expressed concern about the lack of federal outreach to reassure people that the vaccine is safe.

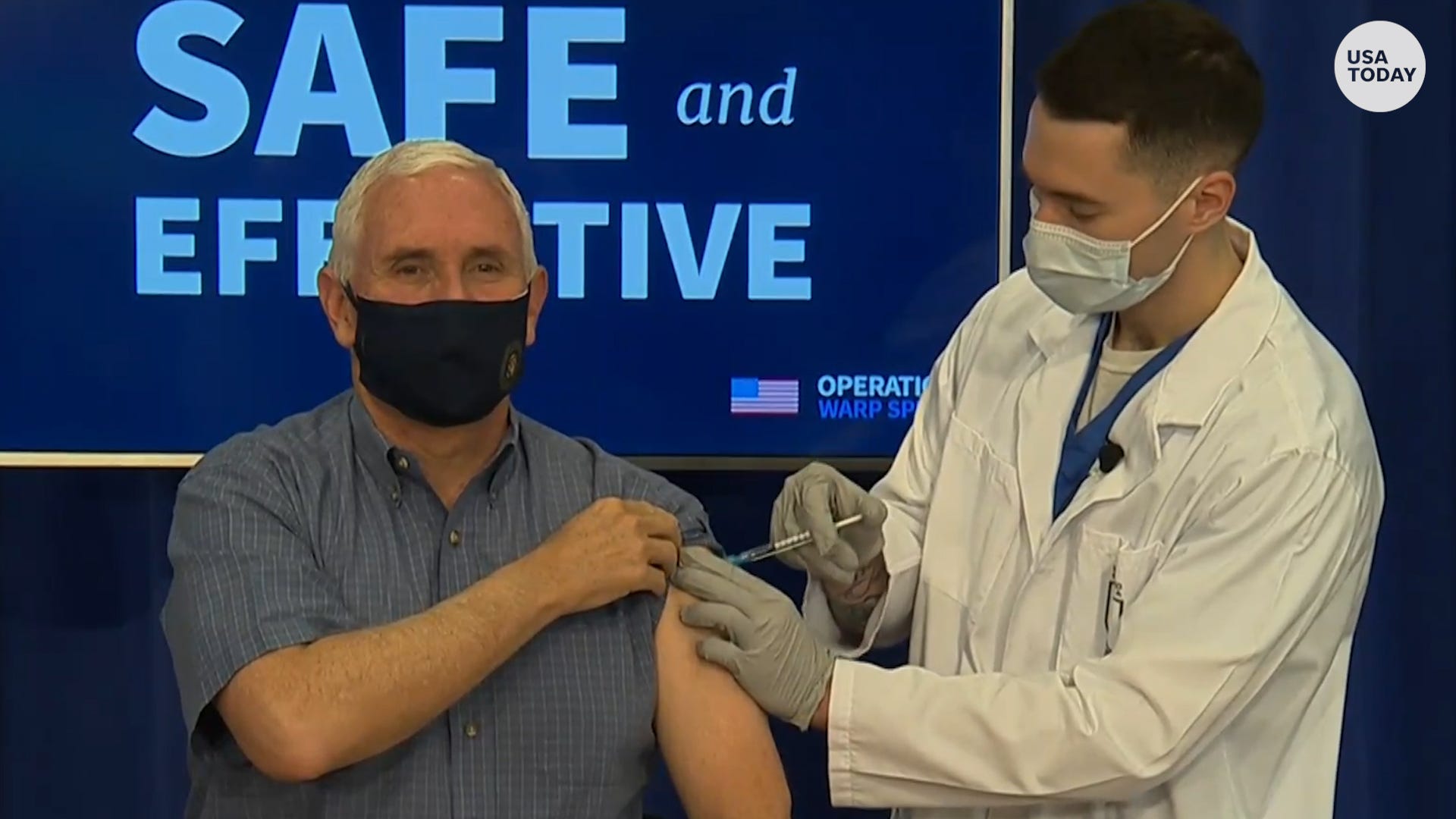

Peter Pitts, president and cofounder of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, said it's important that Vice President Mike Pence was publicly vaccinated this week. That "sends an important message to his core constituency – many of whom are vaccine skeptics – that now is not the time to allow lingering political animus to trump public health priorities."

More still needs to be done, he said, to reach out to communities of color who are hesitant to take the vaccine.

"Having an abundance of safe and effective vaccines is a tremendous victory," said Pitts, a former Food and Drug Administration associate commissioner for external relations. "Failing to coordinate access and convince our fellow citizens to roll up their sleeves and do the right thing would be an inexcusable failure."

People will need to be reminded to get their booster shots – both vaccines authorized so far require two doses – and to continue taking precautions like wearing masks and maintaining distance until transmission has been stopped, said Sandra Crouse Quinn, senior associate director of the Maryland Center for Health Equity and chair of the department of family science at the University of Maryland School of Public Health.

"All of that said, and of course, I could say more," she said, "these are fabulous developments – the first glimmer of a light at the end of the tunnel."

How we did it

USA TODAY asked scientists, researchers and other experts how far they think the vaccine development effort has progressed since Jan. 1, when the virus was first recognized. A dozen responded. We aggregated their responses and calculated the median, the midway point among them.

This month's panelists

Pamela Bjorkman, structural biologist at the California Institute of Technology

Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease expert at the University of California, San Francisco

Sam Halabi, professor of law, University of Missouri; scholar at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University

Florian Krammer, virologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City

Dr. Michelle McMurry-Heath, president and CEO of Biotechnology Innovation Organization

Dr. Kelly Moore, associate director of immunization education, Immunization Action Coalition; former member of the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; chair, World Health Organization Immunization Practices Advisory Committee

Prakash Nagarkatti, immunologist and vice president for research, University of South Carolina

Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and a professor of Vaccinology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

Peter Pitts, president and co-founder of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, and a former FDA Associate Commissioner for External Relations

Dr. Gregory Poland, director, Mayo Clinic's Vaccine Research Group, and editor-in-chief, Vaccine

Sandra Crouse Quinn, senior associate director of the Maryland Center for Health Equity, and chair of the department of family science at the University of Maryland School of Public Health

Prashant Yadav, senior fellow, Center for Global Development, medical supply chain expert

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com and Elizabeth Weise at eweise@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.