Content warning: This story references incidents of self-harm.

Trouble started, as it often does, with a romantic rivalry.

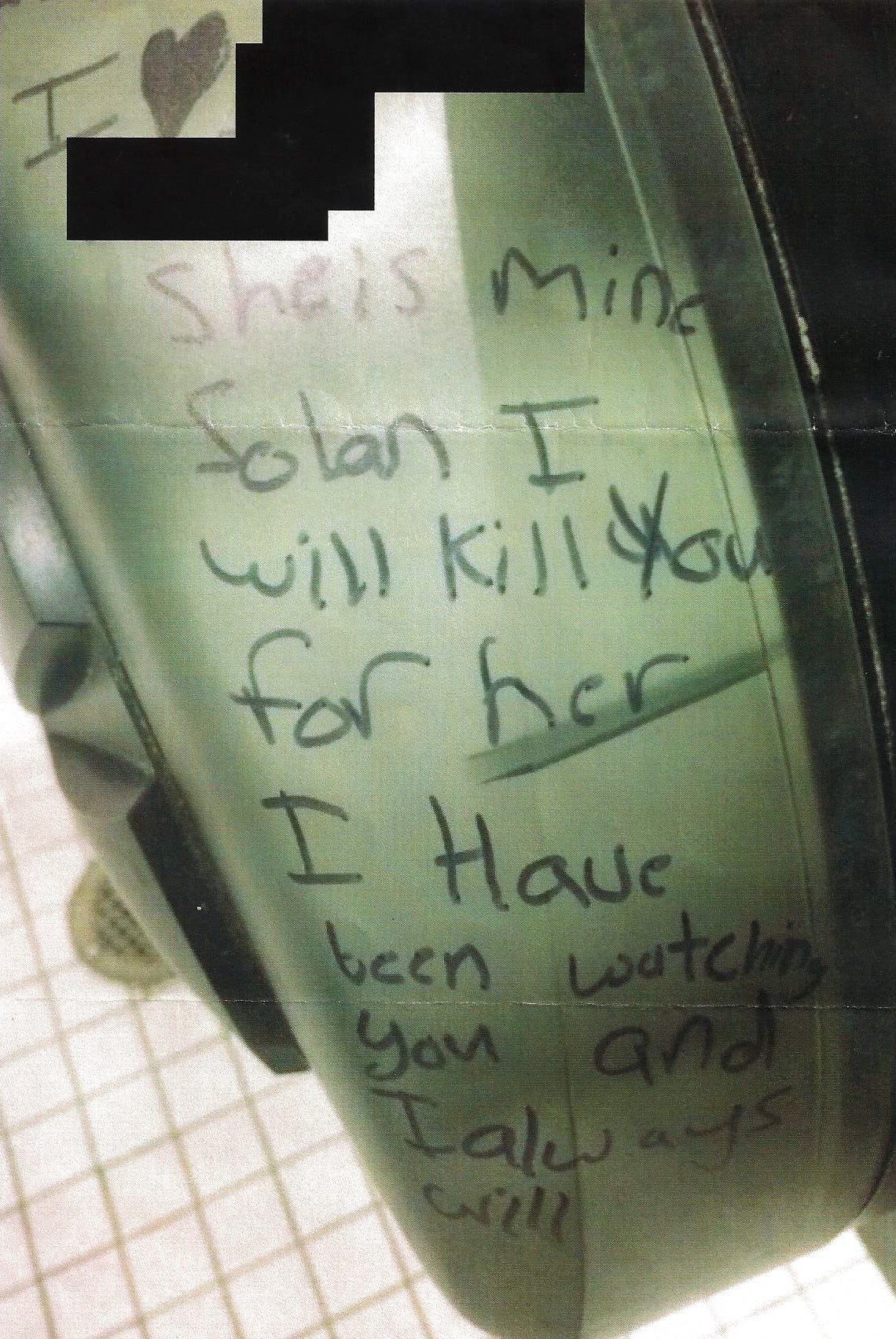

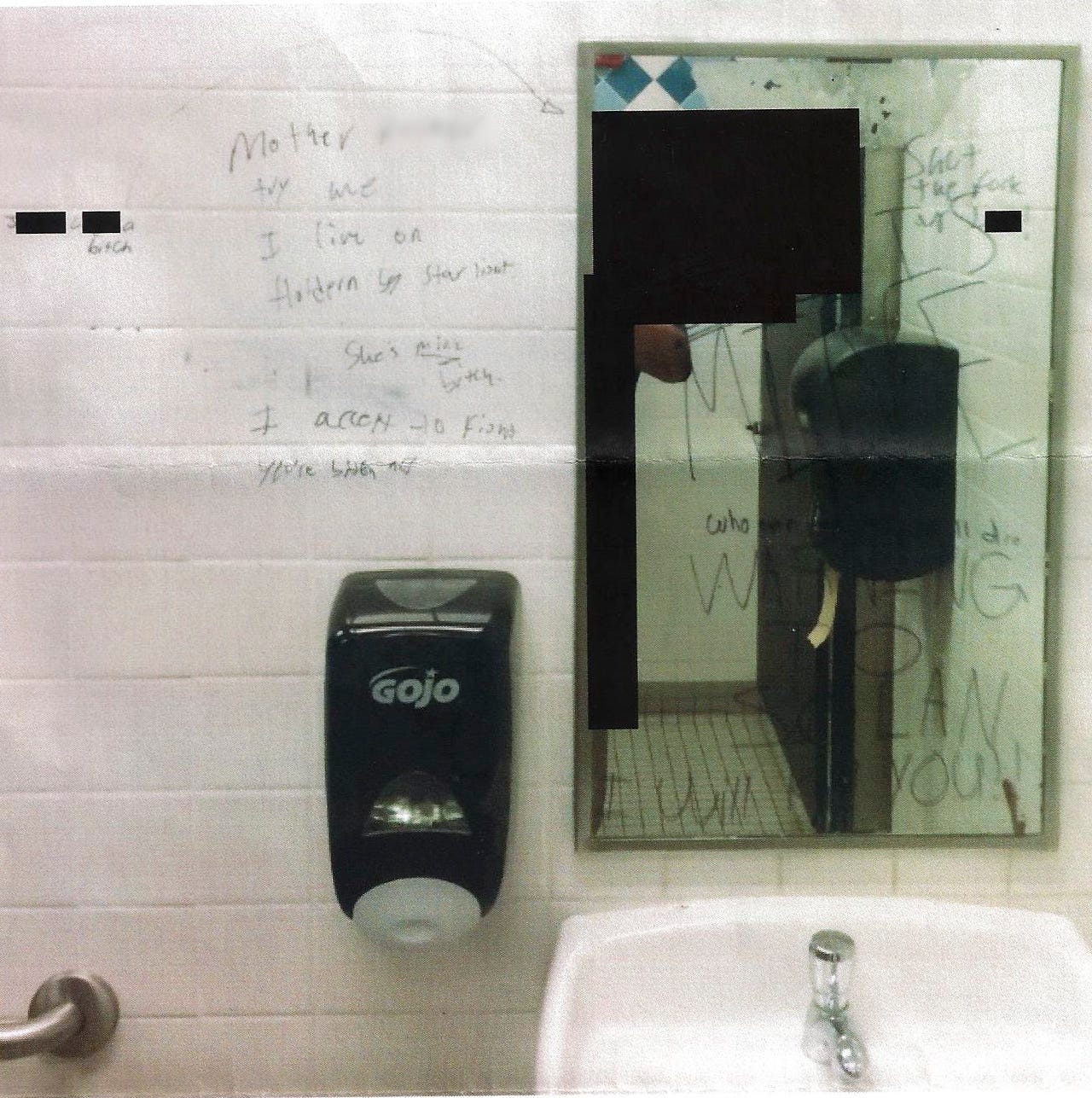

One teenage boy, a student at Charlotte High School in Punta Gorda, warned his schoolmate, Solan Caskey, to stay away from a certain teenage girl in a series of Sharpie-penned messages on the school’s bathroom wall. Solan, being a teenage boy himself, impulsively responded with his own graffiti, including:

"Mother f---er try me," "She's mine, bitch" and "I accept to fight..."

The exact details of what happened immediately after this 2017 exchange are uncertain. But a day later, a police report shows that the school resource officer and a school psychologist concluded Solan was suicidal and possibly wanted to kill other students.

Solan denied this at the time (and still does), but the officer forced him to the ground and handcuffed him before taking him to Charlotte Behavioral Health Center in Punta Gorda for a potentially multi-day forced stay.

There, he got a mental health examination under the state's Baker Act — making his case one of a record 32,763 such evaluations of Florida children that year.

Such mental health checks have been outpacing child population growth statewide — and in regions like Southwest Florida, by leaps and bounds — for nearly a generation.

In the last 10 years alone, they have more than doubled in Lee, Collier and Charlotte counties, far outpacing population growth. There are now more than 2,200 such cases involving children every year in this region.

Many see this as a sign of increased awareness of mental illness in children at a time when data show that suicidal thoughts and actions among those younger than 18 are increasing. Their increase also tracks with the rise of mass shootings in the United States, and a heightened awareness of that threat, particularly in schools.

But some parents, counselors and other mental health experts say the rapid increase in such forced examinations, which are designed for only those likely at immediate risk of harming themselves or others, suggests that the law is being used more as a disciplinary tool than a mental health aid.

And, they argue, taking kids into custody who are not actually suicidal or credibly threatening others’ lives – often in handcuffs and in the presence of their peers – may worsen conditions like chronic depression and anxiety.

Read more in this series: Explore the mental health crisis faced by Southwest Florida's kids

Read our editorial: How to address the rise in juvenile Baker Act committals in Florida

In Solan’s case, medical records show that a psychiatrist interviewed him the next day and determined he was not a threat.

District spokesman Michael Riley, citing federal student privacy regulations, refused to discuss this particular incident. He responded via email only to say that children receive Baker Act referrals at school to "protect the child from doing harm to themselves or others."

Solan’s mother, Hilary, doesn’t buy that. And she remains livid.

“They want to use (the) Baker Act for any behavioral problem — anything that they don’t like," Hilary Caskey said. "If you have any kind of outburst, if you have any kind of emotion whatsoever and you are not just an order-following automaton, they will Baker Act you.”

The Florida Mental Health Act of 1971, commonly referred to as the "Baker Act" in reference to the law's original sponsor, allows for voluntary or involuntary mental health evaluations of up to 72 hours for people who have mental illnesses and are considered an immediate threat to themselves or others.

The law and its many amendments over the decades were designed to bring a consistent process to treating individuals with mental illness and to set forth —and, thus protect — their civil rights.

But some question whether the nearly half-century-old law is living up to its original intent, particularly as it relates to children.

Law enforcement officers, who have limited training in mental health issues, are usually the ones deciding whether a child should be sent to a psychiatric facility for an evaluation. This is especially true in the schools, which may or may not have an on-site psychologist.

Another problem: psychiatric committals are often the first and only resort in emotionally charged events, said Rafael "Alex" Olivares, executive director of the Lee County-based Center for Progress and Excellence Inc., a mental health services provider for Southwest Florida.

More: How daily meditation helps kids from some of the toughest Fort Myers neighborhoods

And: Unequal treatment: Children's mental health dollars vary across state, Southwest Florida

"In some cases, what's not happening is a de-escalation of these situations that may prevent them from happening," Olivares said.

The not-for-profit received a $1.2 million state grant last year to create mobile crisis units to respond to and assess such events in Lee, Collier, Charlotte, Hendry and Glades counties. Their goal is to prevent forced Baker Act evaluations when appropriate.

For now, it remains a program that only responds to a minority of Baker Act cases in the region — a fact likely owing to its modest size and that it is still relatively unknown to the public. Olivares expects that to change now that he has inked deals with Lee and Collier's public schools to get called for all Baker Act cases starting this school year.

"Maybe this prevents a child from getting handcuffed, taken and having to spend the night in a facility away from their family — the whole thing, which is pretty traumatic," he said.

▪ ▪ ▪

This was the second time Solan Caskey had been Baker-Acted. The first happened when he was 10 years old, following a temper tantrum in elementary school. The family said Solan struggled with a resource officer that time too.

A psychiatrist cleared Solan shortly after he was detained that first time, according to his mother. The family pulled the boy out of school and homeschooled him until he reached high school age four years later.

Solan was a sophomore when his second Baker Act detention happened after the bathroom graffiti exchange.

"Before I got tackled the second time, I knew exactly what was going to happen. I had a familiar feeling," he said. "I had tears streaming down my eyes because I knew what was going to happen."

School administrators initially gave Solan a three-day internal suspension and notified his parents that he had gotten into trouble, his family said. He went to school the next day.

But, by 11:30 that morning, the school called Hilary Caskey to tell her that Solan was in an ambulance and on his way to Charlotte Behavioral Health's crisis stabilization unit for a Baker Act evaluation.

"The Juvenile (Solan) advised he wanted to kill other people as well (as) he didn't care to live anymore," the police incident report of the event states. "This all stems from a girlfriend problem that he is having. The Juvenile further advised that most days he wishes he would just die."

Nothing in the report indicates that Solan had weapons or any specific plan to harm other students.

Officers claim Solan resisted them, resulting in a scuffle on the ground. He suffered some quarter-sized scrapes and bruises to his head, according to the incident report and photographs Hilary Caskey took of the boy shortly thereafter.

A fuzzy Snapchat video another student shot of the incident, and later posted on YouTube, also appears to show the school resource officer hitting Solan's head with the handcuffs before putting them on the boy. A subsequent Punta Gorda Police Department internal investigation determined that the school resource officer did nothing wrong.

After the incident, Solan transferred to The Academy in Port Charlotte, an alternative high school, from where he graduated. He later joined the Army National Guard.

“They completely broke everything that was supposed to be set up to protect him,” Hilary Caskey said. “They set him up to fail. They beat the crap out of him. And they locked him in the psych ward.”

Whatever the merits of a given Baker Act evaluation of a child, some parents interviewed for this story say schools don’t consult them before police detain their children and take them to mental health crisis units, often in violation of written school policies.

Lake Trafford Elementary School in Immokalee determined that Myda Carmago's 8-year-old was suicidal in February after he allegedly threatened to choke himself with pieces of ripped paper and hold his breath until he died. Both are physical impossibilities.

The child had recently been diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and an anxiety disorder, according to the family. Carmago, an Exceptional Student Education assistant at Immokalee Middle School, said she had already been sending him to a therapist once a month.

The boy had established a special education plan with the school, known as an Individualized Education Program, to govern any behavioral issues he might have, she said.

Previous coverage: She's 16 and suicidal, but an overburdened system responds in slow motion

Read our editor's note: A crisis without end: Florida ranks last among states in spending for mental health

Part of that included a requirement that the family be notified of any problems before any significant actions, such as a Baker Act referral.

But the school called the family only after the boy was on his way to the crisis unit at The David Lawrence Center in east Naples, Carmago said. School officials declined to comment on the incident, citing student privacy regulations.

He got there after the psychiatrist had left, meaning he had to stay overnight before getting a required mental health examination. He was released 11 a.m. the following morning, shortly after that interview, records show.

The center's medical evaluation of the boy indicated that he was depressed, noting that he was struggling academically in school. They also stated that he had expressed frustration about school and had a “wish to be dead.” But the center's staff ultimately deemed him a low risk for suicide, according to the report.

Carmago has since decided to homeschool the boy with the help of his grandparents. She said his behavior and mood have improved.

"My 8-year-old son was required to spend the night at this hospital surrounded by children with inexplicable mental problems, away from his parents for the first time in his life and I could do absolutely nothing about it," Carmago said. "To have our child essentially kidnapped from school and locked up in a mental ward was the most frightening situation we have ever faced."

▪ ▪ ▪

Data collected by the state shows just how common the Baker Act committals involving children have become in Florida:

- Between the 2001-02 through the 2017-18 state fiscal years, Baker Act examinations of children increased nearly 141 percent. That rate is far outstripping population growth. Florida’s number of children younger than 18 will have grown an estimated 19.5 percent between the 2000 and 2020 censuses, according to the state’s Office of Economic and Demographic Research.

- The sharpest increase in committals – 84 percent – was among children between the ages of 14 to 17, according to a 2017 state report. But even the committals of children between the ages of 5 and 10 grew 76 percent.

- The number of Baker Act committals of children statewide has grown all but two years between 2001 and 2018. The percentage of such cases grew by more than 10 percent last budget year, the fourth largest increase during this period.

- Over the last 10 years, the rate of Baker Act committals involving children has more than doubled in Southwest Florida. In Lee County, the rate grew from 689 per 100,000 children to 1,385 per 100,000. The rates in Collier increased from 337 to 896 per 100,000. In Charlotte, they jumped from 894 to 2,688 per 100,000 children.

Nearly a quarter of Baker Act committals involving children took place at schools and were initiated by law enforcement, according to a 2017 task force report on the issue.

School administrators say they don’t track such cases themselves. And the 2017 report did not specify how much school-based Baker Act cases has changed over the years.

But a News-Press review of law enforcement calls between 2000 and 2017 in Lee and Collier counties show that such school-based cases have grown sharply.

They were once a near rarity in Lee and Collier schools, which averaged roughly 20 or so such cases a year between 2001 and 2009, records show. But, between 2010 and 2017, Lee County law enforcement Baker-Acted an average of 117 children a year. The Collier annual average more than doubled to 52 such cases.

Some schools averaged multiple Baker Acts a month per school year. Many happen even at the elementary school level.

In Lee County, all children subject to the mental health law are handcuffed as a matter of Sheriff’s Office policy. Other jurisdictions similarly mandate cuffing or, in the case of, say, Collier County, leave it up to individual deputies.

“I do think there is some overreaction," said Dr. Omar Rieche, a pediatric psychiatrist in Fort Myers who has practiced in this region for more than two decades. "Part of it is the mandate the school staff has to keep the environment safe so everyone can be learning. So, when you have a child with emotional/behavioral problems, it escalates very quickly."

Stacey Brown, a practicing mental health counselor in Fort Myers who won a Golden Apple in 1998 when she worked as a school counselor for Lee County's school district, said many outbursts leading to Baker Act evaluations might better be solved by simply talking to kids about what's behind their outbursts.

“We need to take all threats seriously, of course. But if we had more resources we could probably figure out if somebody had just failed a test, or there are problems at home, and this is not really a suicidal child requiring the Baker Act,” Brown said. "But, from a liability standpoint, I can completely understand why the schools would be concerned.”

▪ ▪ ▪

Gov. Ron DeSantis signed into law this year a bill requiring schools to establish standardized suicide assessments before initiating Baker Acts. It remains to be seen what, if any, impact this will have on the rapid growth of such cases and whether it will lead to better mental health outcomes.

Officials with the Lee, Collier and Charlotte school districts said the decision to place a child in custody under the Baker Act is not taken lightly. They also — each, in separate interviews — are quick to note that such cases are largely triggered by school resource officers, not school administrators.

“Our last resort is a Baker Act," said Lori Brooks, director of school counseling and mental health services for Lee County Schools. "If we can work to engage families and avoid that Baker Act, we do it as much as we possibly can.”

Capt. Mike Miller, who oversees youth and Baker Act services at the Lee County Sheriff’s Office, said he does not know why cases have increased so much in the region.

Miller guessed that it may be partly the result of population increases (though the cases are far outpacing that), increased use of social media for bullying and more broken families. He said that some of the affected children also come from neighborhoods where crime and violence are common.

He adds that he does not believe the Baker Act is being overused.

“I don’t think you can over-react when it comes to a kid threatening suicide. I think you can under-react,” Miller said. “You know we’re just not taking kids and putting them in handcuffs and putting them in a mental health facility because they say they want to harm themselves,” he said. “They have a plan and they have thought about it.”

The Baker Act states that a person cannot be held for involuntary mental health evaluation for more than 72 hours.

Within that period, patients must be released (assuming no crime has been committed), agree to inpatient or outpatient follow-up treatment, or a petition must be filed with the circuit court seeking an extension of involuntary placement in a mental health facility.

In that latter case, patients are entitled to public defenders who can explain their rights and the pros and cons of such committals.

But the region’s Office of the Public Defender is usually not notified about children. The reasons for that aren't entirely clear, though it's possible that parents and guardians simply acquiesce to doctors' recommendations.

A bill that would have allowed public defenders to have access to all people in Baker Act receiving facilities died in the last legislative session.

Resources in Southwest Florida: Struggling with a mental illness? Here's how you or your child can find help

“There are lots and lots and lots of kids being Baker Acted that, if they were adults, would be entitled to (legal) counsel," said Kathleen Smith, the elected public defender for Charlotte, Collier, Hendry, Glades, and Lee counties. "Since the children have no representation we don't know anything about who they are, how they got there, how long they are remaining in the hospital, whether they are appropriate to be in a hospital or not."

By contrast, the Public Defender’s office routinely handles such adult cases.

“A child should know what their options are, just like if the child were in delinquency court," Smith said. "They should have access to a lawyer."

▪ ▪ ▪

For all its perceived flaws, The Baker Act is often a lifesaver for children that provides the first step to mental health recovery. Though it’s rarely a smooth path.

Sarah Doherty, a Naples teenager, tried to kill herself three times. Even now, years later, the subject remains a difficult one for her to talk about.

Sarah, now 17, and her mother, Karen, left New Hampshire for Florida about three years ago to get away from the girl's father, who Karen Doherty said had long been emotionally abusive.

Sarah said she blamed herself for the subsequent divorce. She started cutting herself with razor blades and drinking alcohol to numb the psychological pain.

“I felt like it was my fault because I just thought I wasn’t good enough,” Sarah said. “I couldn’t do anything to help.”

Her mother enrolled her in a private religious school in Naples. The girl acted out and clashed frequently with classmates and teachers. She was bullied. Often.

One day, while Karen Doherty was cleaning Sarah’s room, she found a very bloody towel in her backpack. She also found bottles of wine and beer and a cache of razors, some rusty.

“It was like someone was massacred in her room,” Karen Doherty said. “It was horrible.”

She pulled the girl out of school, called 911 and had her sent to The David Lawrence Center’s crisis stabilization unit under the Baker Act. Sarah spent three days there.

Sarah still says it was a miserable experience. And, soon, she was back to her old ways, even though Karen removed all alcohol and sharp knives from the home.

One night, she had texted a friend that she wanted to kill herself. Her friend called the police, who then went to the house. Sarah was Baker-Acted a second time.

Things didn’t change until, after that second psychiatric committal at The David Lawrence Center, she found a new therapist and a treatment plan that focused on changing behaviors and negative thinking patterns.

“The David Lawrence Center helped me save my daughter's life,” Karen Doherty said.

Sarah describes the ensuing conversations and the ongoing experience with the therapist as a “love-hate relationship.” She was called out on her bad behavior and unhealthy thinking. And the therapist explained in detail how her actions affected others.

It was annoying, Sarah said. But it helped.

“She held me accountable, which was really good,” Sarah said. “She would push me to do better, to do things. Like, ‘Hey, Sarah, why don’t you try going to class today instead of crying in the bathroom?’ And, I’m, like, ‘OK, I guess I can do that.’”

She said she has since stopped cutting herself and has an improved outlook on life. She no longer blames herself for her abuse and her parents’ divorce.

Her treatment continues.

Follow this reporter on Twitter: @FrankGluck