Record Democratic field of White House contenders in 2020 signals an unpredictable race ahead

Susan Page

Susan PageWASHINGTON – Senators and representatives and governors and mayors and billionaires and a former vice president.

Oh, my.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., told TV host Stephen Colbert on Tuesday night that she was launching an exploratory committee for a presidential campaign. Earlier in the evening, Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, announced on MSNBC that he was heading out on a tour of the four states that hold the opening contests. In the morning, Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., said even her in-laws signed off on her prospective race. Saturday, former HUD Secretary Julian Castro formally announced his candidacy in his San Antonio hometown. Friday, Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii, declared she would run, too.

An unprecedented field is gathering for the Democratic presidential nomination – a group that is smashing records in size and diversity, in generation and geography. A sprawling group of contenders with no presumptive front-runner sets the stage for an unpredictable contest – one that is already underway.

Prep for the polls: See who is running for president and compare where they stand on key issues in our Voter Guide

At stake is not only the Democratic Party's nomination but also its direction.

Some Democratic voters, united most of all in their desire to deny President Donald Trump a second term, relish the early jockeying.

"I don't know many Democrats who are rolling their eyes and saying, 'Oh, no, the Democratic primaries are already starting,' " said Jennifer Palmieri, a top aide to Hillary Clinton's 2016 campaign and the author of "Dear Madam President: An Open Letter to the Women Who Will Run the World."

"Are Democratic voters going to be shopping around or make a quick purchase?" Palmieri asked, then answered: "I think they're going to shop around."

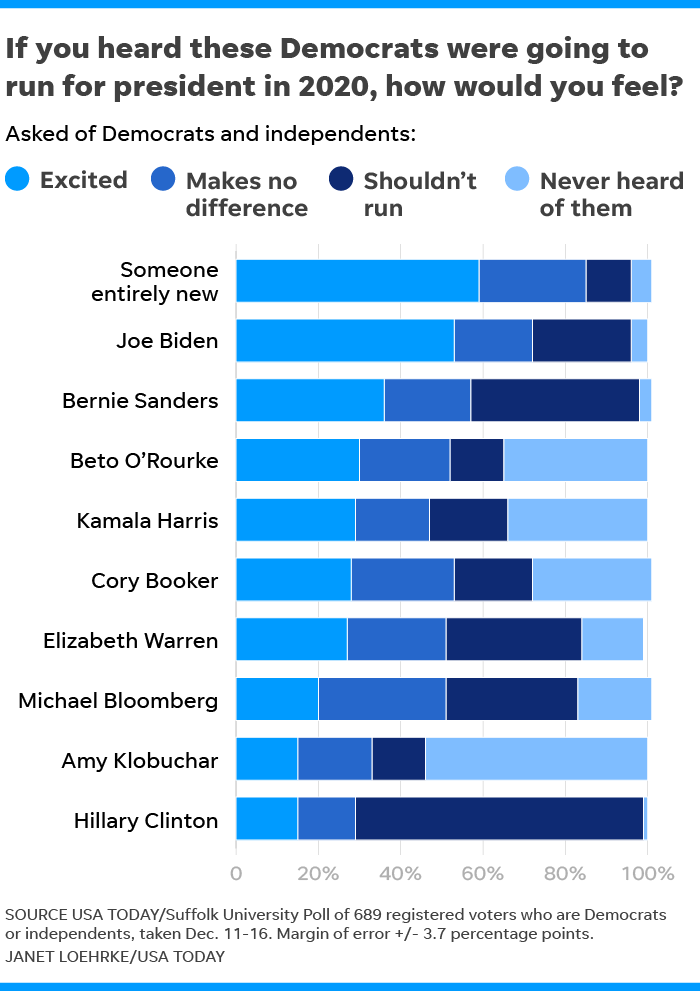

In a USA TODAY/Suffolk University Poll in December, the 2020 option that generated the most interest among Democratic and independent voters wasn't an individual; it was an unspecified "someone entirely new." Nearly six in 10 said they would be "excited" by that prospect, edging out even Joe Biden, the former vice president who is weighing whether to make his third bid for the top job.

About 30 Democratic officeholders and activists have signaled they are considering the contest, and there may be more who are just waiting to be noticed. The field is poised to outpace the 17 credible candidates who competed at some point for the 1976 Democratic nomination, the largest number ever. For Republicans, a record 17 credible candidates ran at some point for the 2016 nomination.

That was the year the GOP chose Trump, a real estate developer and reality TV star competing against establishment favorites. In the 1976 Democratic contest, Jimmy Carter, the one-term governor of Georgia who initially had been given distant odds, won the Iowa caucuses and the party's nod.

Lessons learned from that history: The biggest fields can end up nominating the candidates who seemed at the start to be the least likely to prevail.

For the first time, the credible contenders for a major party's presidential nomination include not only multiple women but also multiple candidates of color. They range in age from their mid-30s (South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, California Rep. Eric Swalwell and Gabbard) to their mid-70s (former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and Biden).

Even in geography, the contenders hail everywhere from Vermont and Massachusetts to California and Hawaii, from Minnesota and Montana to Texas and Louisiana.

This year's Democratic contest has become a full employment program for political consultants, especially those who have worked in national campaigns or have experience in such key states as Iowa and New Hampshire. Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who formed an exploratory committee, made a splash this month by landing Sanders' former Iowa caucus director, as well as veterans of the caucus teams for Clinton and Barack Obama.

"The talent race" is one of the early metrics watched at the beginning as closely as fundraising and name recognition, said Stephanie Cutter, deputy campaign manager for Obama in 2012. The big field speeds up the timetable for candidates to launch, she said: "Unless your name is Joe Biden, you get started earlier."

What are other potential repercussions of this historic field?

1. This could go on for a while

The opening Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary about a year from now, followed in short order by the Nevada caucuses and the South Carolina primary, traditionally winnow a field of candidates to a front-runner and a challenger or two. In a big field, a candidate could finish first in a state with just a fraction of the vote, and several candidates could claim slices of the electorate.

Democratic rules require proportional distribution of convention delegates, which means any candidate who garners 15 percent or more of the vote in a state gets some of its delegates. That could keep more candidates in play longer, and it could enable them to divide their attention among states.

On the other hand, there's California. The nation's largest state moved up its primary to the earliest date that rules allow, on March 3, 2020, immediately after the opening contests. During the state's early voting, California Democrats could get primary ballots at the same time Iowa Democrats line up for the caucuses. (Texas and seven other states also scheduled their primaries for March 3.)

Unlike Iowa and New Hampshire, competing in California traditionally depends not on personal contact but on millions of dollars' worth of media ads, a reality that favors leaders over long shots.

"Candidates are going to have to play a three-dimensional game of chess," says Mo Elleithee, founding director of Georgetown University's Institute of Politics and Public Service. "I just think it's anybody's ballgame."

More:With earlier primary date, California seeks 'larger role' in 2020 election process

More:Democratic officials schedule 12 debates for 2020 as they brace for huge field

2. Breaking through is hard to do

Being widely known is an asset, at least at the start. Biden and Sanders would be all but guaranteed to win a seat on the debate stage, for instance. Under rules released by the Democratic National Committee last month, participation in a dozen official debates, which will start in June, will be determined by poll standing and grass-roots fundraising.

For less well-known candidates, those who have competed only in a single state or city or congressional district, breaking through can be hard to do. The lesson from the breakout stars of the 2018 midterms, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Beto O'Rourke of Texas, was the power of projecting authenticity and doing it on social media.

That may help explain why O'Rourke posted an Instagram video last week of him getting his teeth cleaned while he asked his dental hygienist what she thought about border security – TMI, some on Twitter said – and California Sen. Kamala Harris posted photos of her cooking a pot of gumbo with her sister. Then there was Warren, who ducked briefly off-screen in an Instagram video to grab a bottle of beer. A Michelob Ultra, she said later.

3. At the end, nobody may have a lock

To be nominated at the Democratic National Convention in July 2020, in a city yet to be selected, a candidate will need the support of 2,026 delegates. If enough candidates collect delegates through the primaries, it's possible that even a clear front-runner won't command the majority he or she needs.

The last time a convention opened without a candidate holding a lock on the nomination was in 1976, in Kansas City, when Republican President Gerald Ford was in the final throes of his battle against challenger Ronald Reagan. The last time multiple ballots had to be held to choose a nominee was at the Democratic convention in 1952.

In Chicago that summer, Tennessee Sen. Estes Kefauver had the most delegates in the first round, but Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson prevailed in the third. In Kansas City, Ford prevailed.

Democrats might want to remember the problem with divided conventions: They can leave divided parties. Ford and Stevenson lost in the general election in November.

4. It's not just who. It's what

At stake for Democrats is not only who leads the party in the 2020 election but also what the party stands for.

A presidential candidate becomes the face of a party, and a president has the power to define what his party stands for. Witness Trump: He reshaped the GOP into a more populist party on issues including trade, tariffs, fiscal discipline and the U.S. role in the world, increasing its support among white men and blue-collar workers, albeit at the expense of college-educated voters, especially women.

"Does a Howard Schultz define the party differently than a Sherrod Brown?" Cutter asked, comparing the former CEO of Starbucks with the Ohio senator. "Yes, by their resumes," and more. Candidates from deep blue states such as Massachusetts and California are likely to bring a different electoral approach than, say, Montana Gov. Steve Bullock, who won a second term in 2016 even though Clinton carried 36 percent of the vote in his red state.

The Democratic Party, like the GOP, has been changing. For the first time in a quarter-century, a majority of Democrats identify themselves as "liberal," Gallup reported last week. In the midterms, outspokenly liberal candidates ran competitive races in unexpected places – say, Stacey Abrams' narrow loss for governor of Georgia.

"Medicare-for-all," a rallying cry for Sanders in 2016, has become more widely endorsed, although there is still a debate over what the catchphrase means and how it should be financed. Ocasio-Cortez and other liberals push the "Green New Deal," which could include a federal jobs guarantee and 70 percent marginal tax rate on the super-rich.

In the Democratic primaries, there will be a debate over such policy issues. And, of course, on how to defeat Donald Trump.

More:USA TODAY/Suffolk Poll: What do Democrats want in 2020? Someone new