New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

Think about your stride for a moment–driving one knee up at a time, opening up the opposite hip to extend the leg that is taking the ground force, then switching. You wouldn’t be able to do any of those movements if not for the quadriceps, a grouping of muscles that make up your thighs. Your quads also absorb the impact of your foot strike and transfer that energy to your hamstrings to propel your next step.

Preventing a painful and debilitating injury such as a quad strain should be high priority for runners, but it’s often an afterthought—until it happens.

Most of the time, a little soreness in the front of the thighs is no cause for concern. If you’ve recently changed up your training, your quads may experience delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS). But if quad pain is a regular symptom for you, your pain comes on suddenly, or you feel pain even when you’re not running, you could have a more serious injury.

Quad strains and femoral stress fractures both cause pain at the front of the thigh, and both are common among runners, says Kevin Maggs, D.C., director of The Running Clinic and a chiropractor in Gainesville, Virginia.

We’ve rounded up the best advice for keeping your quads happy and addressing issues if they do arise. But first, let’s cover the basics.

What Are the Quad Muscles?

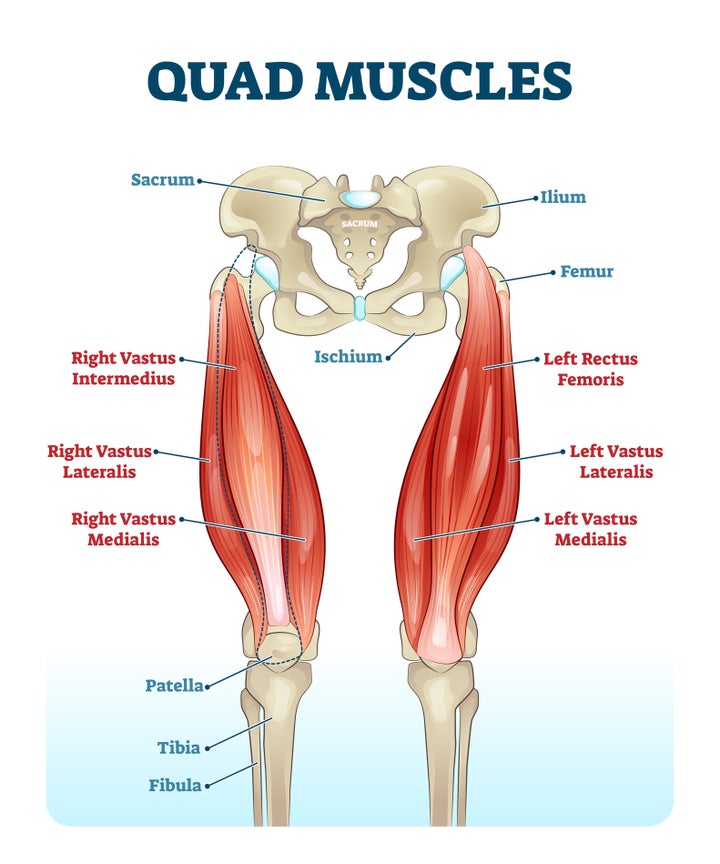

Your thigh is made up of three sets of muscles: hamstrings, quadriceps, and adductors. With the hamstrings, the quad muscles work to straighten and bend your legs. The quadriceps femoris is made up of four sub-components: the rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius. The rectus femoris, which is located near the front of the thigh, is the most commonly injured of the four muscles.

What Causes a Quad Strain?

Training errors are the biggest risk factor for any running injury, Maggs says. If you increase hill work, speed and/or distance too quickly, your body doesn’t have a chance to adapt to the increased demands. For this reason, following a measured and patient training plan is one of the most important things you can do to stay injury free.

A dramatic increase in speed work directly affects the workload of the quads. “As you increase speed, you decrease the range of motion at your ankle and increase range of motion at your hip and knee,” Maggs says. “When this happens, there is more knee flexion and more hip extension, both of which place more strain at the rectus femoris muscle [longest quad muscle] during the swing phase of your gait.”

Landing too far out in front of your center of mass also places more strain on your quads. Increasing your cadence (number of steps per minute) can help limit overstriding and reduce the load to your quads.

Who’s at risk?

- Runners who skip warm ups and mobility work.

- Runners with weak hamstrings.

- Runners with tight hip flexors and quads.

- Runners who overtrain. Muscle fatigue can make your quads more susceptible to injury.

- Runners who have suffered past quad strains. According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, once the muscle has suffered a strain it is vulnerable to re-injury.

What does a quad strain feel like?

Pulling your quad muscles will feel different based on how severe the injury is. A quad strain is generally classified in three grades, according to an article published in the Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. Grade one is mild pain with no to minimal loss of strength. Grade two is moderate pain with moderate loss of strength. And grade three is severe pain with complete loss of strength.

Some people have described the following sensations after straining their quad:

- Deep, burning pain in the top of the thigh

- A light, tender pain

- Hearing a popping or snapping sensation

- Visible bruising and swelling

- Muscle spasms

What Should You Do If You Think You’ve Pulled a Quad Muscle?

Stop running.

If the injury isn’t too bad or you’re unable to see a physician right away, you can self-treat with the RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation) method. With icing, make sure you are not keeping the ice pack on for more than 20 minutes per hour and that you have some sort of barrier between the ice and your skin. This method is especially important in the first 24 to 72 hours after injury.

Get a professional diagnosis.

“While runners traditionally think they have a quad strain, I wouldn’t be exaggerating if I said that 50 percent of runners who’ve come to see me with quad pain had femoral stress fractures,” Maggs says. For this reason, he highly stresses the importance of getting a professional diagnosis when quad pain persists.

Quad strains tend to present as acute pain in a specific part of the muscle. Pain may improve as you start running but then feel worse afterward. A femoral stress fracture feels like poorly localized, deep pain in the thigh. The pain typically worsens as you run and can be present even when your quads are not bearing any weight.

If you’re experiencing minor quad pain during and between runs, it’s possible your body is just adapting to your training. However, Maggs still recommends addressing symptoms before they become something bigger. You may need to take additional recovery days between runs or cut back on speedwork until your pain resolves.

Work toward an active recovery.

If you’ve injured a quadriceps muscle, it’s important to allow time for recovery while also continuing to load the injured tissue. “If you completely take time off, the capacity of the tissue decreases, and when you do go back to running, you’re even more vulnerable to injury if you go back to your previous mileage too quickly,” Maggs says.

He recommends lower-body strength training with short range-of-motion loading, practicing exercises such as squats and leg presses with light loads and decreased ranges of motion as necessary. Maintain your cardiovascular fitness through modalities such as cycling or swimming (you can put a pull buoy between your legs if necessary).

Again, don’t try to diagnose and treat quad pain on your own. An expert who specializes in running injuries can help you identify your unique injury and guide you toward recovery.

As for returning to running, you should have a normal range of motion in the knee, be free of pain, and have your strength returned to near normal. If you’re under close watch of a physician they may work through muscle strength tests with you before they give you the go ahead to run again. According to the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, a mild strain can take two weeks to heal, while a severe strain can take up to two months.

Preventing Quad Strains

Warm Up and Cool Down

A proper warm-up and cool-down routine will prevent your muscles from becoming overly tight and leaving you prone to injury. Your warm up routine should be dynamic with flexibility and activation drills to ease yourself into workout mode. If you’re running in cold weather, you should extend your warm-up routine to give extra time for cold muscles to activate.

Recovering from your run starts with the cool-down. This can include a short jog to end the run as well as stretching and foam rolling.

Optimize Your Cadence

Your cadence or stride rate per minute helps indicate whether you are landing under your center of mass or reaching your legs too far out in front of your body. The slower your cadence, the more likely you are overstriding and the greater the load you place on your hips and knees. Studies have shown that a cadence of at least 180 is optimal for injury prevention.

To determine your cadence, first start running. Once you get to a comfortable pace, set a timer on your watch or phone for 30 seconds and count how many times your right foot hits the ground. Multiply this number by four to find your cadence. The number should be somewhere between 140 and 200. If you find that you’re below 180, aim to gradually increase your cadence by about 5 percent at a time.