Ten down: one to go. After a bruising Premier League draw at Norwich Arsenal’s attempt to rack up an entire first XI of convalescents is now tantalisingly close to succeeding. Although typically the balance in Arsène Wenger’s 10-man injury list is weighted towards midfielders and attackers. The new additions are Laurent Koscielny, Santi Cazorla, and most frustratingly of all given the apparent desire to run him until he explodes, Alexis Sánchez. They join Danny Welbeck (knee), Jack Wilshere (ankle), Tomas Rosicky (knee), Kieran Gibbs (calf), Theo Walcott (calf), Francis Coquelin (knee) and Mikel Arteta (calf).

Study that list for a moment and one school of thought on Arsenal’s injury tally looks increasingly persuasive. The Gulliver Theory of muscular injuries is based on the idea small, short-legged players whose movements involve increased lateral motion, short-passing and intricate attacking geometry, what scientists call trying to walk the ball into the net, are more prone to injuries caused by over-stretching. The theory suggests that because Arsenal’s midfield and attack are smaller and less powerful (on average 4cm shorter than the mean in the league) then they must continually play at the limits of their physical and muscular capacity to compete with larger athletes. In a sport of tiny margins the Lilliputian player is always on the edge of what his tendons and muscles can provide. Hence Arsenal will by definition suffer more physical strains. And hence also the least Arsenal-ish players, those most in scale with their opponents – Olivier Giroud, Per Mertesacker – are injured less often.

This is, of course, an idea concocted on the hoof. There is in reality no Gulliver Theory. It is an invention, albeit in the right light an oddly convincing one. And this is the first point here. Despite the apparent multitude of jobbing injury experts out there, from the voluble international fitness expert Raymond Verheijen to pretty much anybody else with a Twitter account, no one knows with any degree of accuracy why Arsenal appear to have suffered more injuries than other teams.

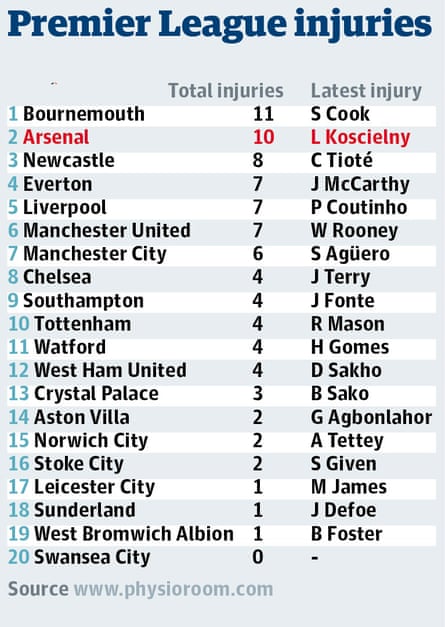

What is certain is the sick list puts them second behind Bournemouth in the Premier League injury table. Beyond this Arsenal have had more injuries overall than any other Premier League team in the past 10 years. At the same time if we are to accept there must be an obvious source of blame for all this, then it must lie either in what happens in training or what happens in matches.

It is worth keeping some perspective. Before Sunday’s triple-whammy Arsenal were joint seventh in the Premier League injury table. Since the start of the season, according to the excellent website physioroom.com, they have had 23 injuries of all types so far. In the same period Manchester City have had 35, Manchester United 30, Liverpool 24, Tottenham Hotspur 20 and Chelsea 18.

Last season United topped the serious injury table ahead of Everton, Newcastle United and then Arsenal. Much like the Premier League table itself, when it comes to injury totals Arsenal are always handily placed, without ever streaking ahead in the way, judging by the more excitable headlines, you might have expected. There is a trend here. But not an overwhelming one.

Similarly Arsenal’s main players do play more then most, but not by much. So far this season nine Arsenal players have started 15 matches or more. This puts them behind Chelsea, level with United and ahead of City, Liverpool and Spurs. Last season Arsenal’s stats on individual matches played were also in the pack with other Champions League clubs. Throw in the fact that only Aaron Ramsey regularly charts near the top of actual distance covered, and the volume of Arsenal’s physical activity in matches doesn’t look like an obvious issue.

Which leaves training. It is here Arsenal have come under scrutiny, notably by the talkative Verheijen, who has accused Wenger of “unconscious incompetence” on fitness matters. It must be said the Dutchman does not watch Arsenal train. He does not have a robust comparison of methods with every relevant Premier League club. He is a self-publicist, specialist in one field giving opinions that leak into others. He is, though, an expert in the field, basing his opinions on private conversations with certain players. His main gripe seems to be Arsenal develop “short-term fitness” over the summer, training “like they are in the marines” rather than building up a more sustainable level. Hence the tendency to suffer around November and December (which others might also attribute to regular high-tension midweek football at that time).

The other chief criticisms are Arsenal do not rest enough in between heavy sessions, and Wenger brings injured players back too soon and does not manage their reintegration, hence the young “core” of regular injured players. What do we have then? A higher than average injury rate. A team who play their main players a little more than most. But no clear details on training errors beyond some distant opinions and Wenger’s own insistence that his medical team are as advanced as any and that players are continually assessed and monitored, including using a GPS system that tracks all their movements in training.

At which point a sense of something based in broader observable reality starts to filter in. As ever, it seems likely there is no magic bullet here. If Arsenal have suffered disproportionately it is likely the cause lies in a combination of more concrete factors. Two points seem relevant. First Arsenal have a relatively predictable first XI. Before any big game it is generally easy to pick Wenger’s team. Arsenal’s key players, those who are most on the ball or in the tackle, tend to play in every testing fixture, the ones where capacities are pushed to the limit. Logic suggests they will suffer wear and tear as a result. There are also questions of fine judgment. In a certain light the recent injuries to Ramsey, Sánchez, Walcott and Cazorla all look, arguably, to have had some man-made contribution. Ramsey should have been rested against Watford just before his most recent injury, a point Wenger conceded for all his gripes with Wales. Sánchez, despite his own gung-ho spirit, was clearly in need of a rest, and not simply because he had already felt his hamstring twang. Chile’s Jorge Sampaoli admitted playing him though injury six weeks ago, since when he has played 12 more matches. Walcott strained his calf 14 minutes after coming on against Sheffield Wednesday in October. The suggestion at the time, watching him rise, cold from the bench in just the fifth minute of the game, was that he had not been able to warm up sufficiently. In a similar vein Cazorla was said to have “played on one leg” in the second half at Norwich, which can hardly have helped his recovery prospects.

There is a suggestion here of a certain carelessness, a slightly chancy attitude towards players already “in the red zone”. Albeit, like every other theory doing the rounds, this too is simply speculation, a conclusion based on outcome. What we can say for sure is that for a decade Arsenal have played a certain way, scaling back physicality in favour of touch and speed of thought. And that in the last year there has been a refusal to pay the necessary asking price to strengthen midfield and attack, increasing the strain on that fine but fragile first team.

Overworked key parts, a lack of muscle generally, a tendency to play the same team in high-tension games. If these sound like causes as convincing as any other, they also reinforce the wider sense there is little wrong with this overstretched team that could not have been solved by shelling out on a strong-arm central midfielder and a high-quality striker last summer.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion