“Ah, Paul Rozin is sort of orthogonal to this whole debate.”

I can’t remember who said it, but I do remember the tone: awestruck, almost reverential, but with a touch of uncertainty as well. Where does Paul Rozin fit in?

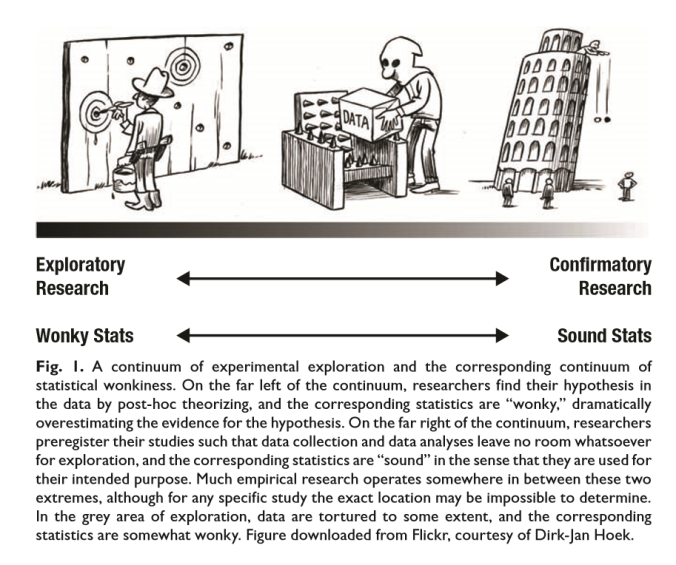

Let’s take a step back. “This whole debate” was referring to the debate about replicability issues, in particular the difference between confirmatory and exploratory analyses. The image and caption below are taken from Wagenmakers, Wetzels, Borsboom, van der Maas, & Kievit (2012), and although it presents the two as fitting along a continuum, it is easy to interpret their paper as saying that only the right extreme counts as confirmatory (it’s an absolute), any deviation from the extreme right counts as exploratory (but can differ in degree of “exploration”).

Wagenmakers and colleagues also strongly emphasize that (despite what the guy in the white mask might imply), they do not actually disapprove of exploratory research as such: “It is important to stress again that we do not disapprove of exploratory research as long as its exploratory character is openly acknowledged. If fishing expeditions are sold as hypothesis tests, however, it becomes impossible to judge the strength of the evidence reported” (p.634).

I agree with this, and I don’t know anyone who doesn’t.

Disagreements do arise, however, and as far as I can see they come from a few different sources. For one, how do we “judge the strength of the evidence reported”, even when we know the analyses were exploratory? Sometimes people seem to vary in their response to this question along some dimension of “suspicion of shoddy practices and ulterior motives”. That is, people who think that the exploration was undertaken using QRPs and researcher degrees of freedom, and was driven by a desire for a flashy result and a quick publication, tend to judge the strength of the evidence as very low. I understand that inference, but I also feel uneasy about employing a heuristic of suspicion and distrust as my default. Then again, greater transparency (which would reduce those suspicions for everyone) could hardly be a bad thing.

Another ongoing debate is about the importance of replicability, as one thing among many for (psychological) science to prioritize. DataColada wants to prioritize replicability because it is the thing which by necessity must come first; Eli Finkel and Paul Eastwick argue that addressing weaknesses in replicability is important, but other (sub)fields may have other weaknesses that – in those cases – should take priority over replicability. In some ways, the confirmatory vs. not distinction maps onto the replicable vs. not distinction, because some of the things that make a study confirmatory are the same things that make it replicable. You can trust the results from confirmatory studies; you can trust the results from replicable studies.

Unfortunately, I think it might be this apparent (but very loose, conceptual) mapping that gives exploratory research a bad name; that makes it necessary to sidebar that “oh but exploratory research is not bad per se” after you’ve extolled the virtues of confirmatory research. Because if confirmatory is replicable, and replicable is trustworthy, and exploratory is the opposite of confirmatory, then exploratory is… unreplicable and untrustworthy. No wonder that the default, when faced with exploratory analyses, for many people seems to be suspicion.

But when I think of these overlapping dichotomies (or dimensions), I often think of Paul Rozin as well.

Because when I think of these overlapping dichotomies, I automatically, easily, naturally, put them in the context of my own subfield of social/moral psychology, where the emphasis is very often on explanation. Experimentation. Isolating causes, and their effects. Extra bonus points if you can demonstrate the mechanism too, through statistical mediation and/or further experimentation. We’re experimentalists, and doing replicable research in this context means high powered designs, experimental control and manipulation of the independent variable(s), solid measurement with well validated scales. Pre-registration of hypotheses and analyses, for extra confirmatory awesomeness, is a good fit with this approach; this “template” for what it is I (try to) do in my research.

But Paul Rozin is orthogonal to that template, to this two-dimensional debate. (Which to be fair, is often much more nuanced than “two dimensions” would imply.) The reason for this orthogonality is best put in his own words, and so you should go and read these three papers. There is chocolate involved! Go do it!

I’ve brought you this far though, so I guess I should explain. Paul Rozin thinks that before you try to explain something, you really need to describe it thoroughly first. He thinks that psychological science, as a whole, has “jumped the gun” by getting into experimenting on causes and effects before having a clear description of the phenomena we are trying to explain. We’ve been asking “why” (or maybe “how”), before we’ve established a clear picture of what, when, where, and who. We’ve been putting process before content, which might be like putting the cart before the horse except I’ve never understood that saying.

In some ways, this fits with one of the boxes which in Eli’s diagram (in this paper and on this blog) is a proximal cause of good science: the discovery box. But while Eli says “We are excited to see journals deemphasizing flashy, phenomenon-focused, atheoretical findings (a practice that arguably prioritized only discovery while neglecting the other features)” I think Paul would say that atheoretical is okay; phenomenon-focused is okay; it just has to be thorough, and descriptive.

But descriptive isn’t quite the same as exploratory, at least not to my mind, and certainly not as an “opposite” to confirmatory. A good description should be highly replicable and trustworthy; if you have a good map you’ll have no problem making your way around the landscape.

There was supposed to be some conclusion to this post, some sort of summary about what kind of exploratory/descriptive work I want to do (especially as it relates to philosophical just war theory). But, Gelman has just published his manifesto for exploratory research, and the main thrust of this blog post is really just that Paul Rozin says really good things about descriptive research (Really! Go and read his articles!) so now I just want to throw this out there sooner rather than later. If you are inspired by Gelman, but are a psychologist rather than a statistician (or both), you may learn something useful from Rozin too.

Pingback: sometimes i'm wrong: status quoi? - part i