Septima Clark was an educator and activist who made enormous contributions to the civil rights movement. Here’s why she deserves just as much fame as Dr. King (and why he thought so, too):

1. She rose from humble beginnings — and the legacy of slavery — to start teaching at age 18.

Septima Clark was born in Charleston, South Carolina in 1898. Her father was born into slavery and didn’t learn to read and write until he was an adult. Her mother was a washerwoman though she was educated as a child in Haiti.

Clark was the second of eight children. Because she couldn’t afford to attend college, she got her teacher’s license after graduating high school in 1916. It was the start of a 40-year career as a public school teacher.

Clark as a young woman

http://blogs.cofc.edu/averyarchives/?p=7

2. She was deeply committed to professional development.

After her husband died in 1925, Clark moved to Columbia, South Carolina, and sent her son to North Carolina to live with his grandparents. Though it was a painful separation, it allowed her to keep teaching and pursue a college degree.

In the summers, she studied at Columbia University in New York, and at Atlanta University. She earned a bachelor’s from Benedict College in 1942, and a master’s from Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in 1945.

3. She never let racism dampen her commitment to teaching and social justice.

In 1916, when she realized she couldn’t work in Charleston because black teachers weren’t allowed to teach there, Clark left the city and began teaching in John’s Island, South Carolina.

When a 1956 state law demanded that she give up membership in the NAACP or lose her job, she moved to Tennessee, where she became the director of education at Highlander Folk School and remained an active member of the NAACP.

4. She fought tirelessly for the fair treatment of black teachers in her home state.

Clark campaigned for a law allowing black teachers to work in Charleston’s public schools, which was passed in 1920.

She also worked with Thurgood Marshall on legislation that gave black teachers equal pay in Columbia, South Carolina.

5. Clark helped thousands combat racism through education.

With a loan from the Highlander Folk School, Clark helped found the first Citizenship School on John’s Island in 1957. In addition to providing social justice training to civil rights activists, Citizenship Schools taught literacy as a means to civic freedom for poor blacks who had never received schooling. They learned practical skills, like how to fill out driver’s license forms, read the newspaper, and open a bank account.

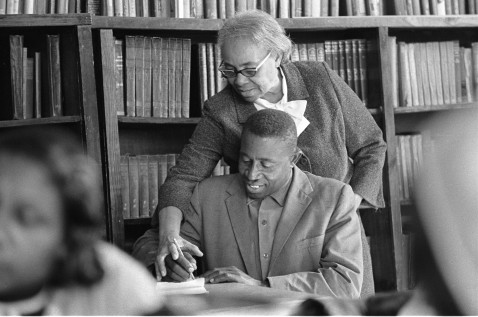

Clark with a student in Wilcox County, Alabama

http://thislittlelight1965.wordpress.com/tag/septima-clark/

By 1970, there were Citizenship Schools all over the South — nearly 10,000 teachers and 200 schools in all.

6. She paved the way for the (recently gutted) Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Through the workshops she led at Highlander, and the curriculum she designed for Citizenship Schools, Clark helped thousands learn to sign their own names and read the Constitution so they could pass literacy tests designed to exclude blacks from voting. She also taught them to read and understand the voting laws in their state.

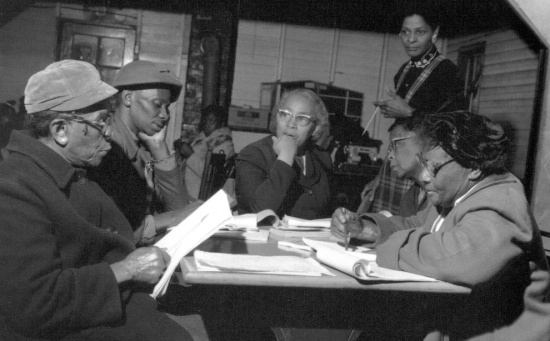

Clark (center) at one of her Citizenship Schools in South Carolina.

http://www.crmvet.org/images/imgeyes.htm

7. Threats of violence and jail time couldn’t stop her.

Though she experienced troubling incidents — including being physically threatened by the KKK in Natchez, Mississippi in 1965, and getting arrested for teaching integrated classes in 1959 — Clark pressed on.

“None of those things discouraged me,” she said.

8. Her teaching inspired Rosa Parks, John Lewis, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Four months after attending one of Clark’s workshops at Highlander, Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her bus seat to a white man — and sparked the Montgomery bus boycott. Parks said of Clark, “I wanted to have the courage to accomplish the kinds of things that she had been doing for years.”

Clark (left) with Rosa Parks at the Highlander Folk School in 1955, right before the Montgomery bus boycott.

http://www.crmvet.org/images/imgeyes.htm

John Lewis, another famed civil rights leader and current Georgia Congressman, was also profoundly influenced by Clark’s teaching at Highlander.

In his memoir Walking with the Wind, he writes, “What I loved about Clark was her down-to-earth, no-nonsense approach, and the fact that the people she aimed at were…the same ones I could identify with, having grown up poor and barefoot and black.”

When Martin Luther King, Jr. won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, he had Clark join him at the ceremony because he felt she deserved just as much credit for her work.

Clark has remained a relatively unsung hero of the movement. Lewis admits: “Her name might be generally unknown today, but she was a powerful influence on many of us during that formative time.”

9. She was an outspoken feminist.

Clark criticized the men she worked with who dismissed her and other women’s contributions to civil rights, calling their sexism “one of the weaknesses of the movement.”

In 1958, she spoke to the National Organization of Women about black and white women’s shared struggle against male domination.

She even encouraged the use of birth control in a time when the matter wasn’t openly discussed. Clark realized that too many black women and children suffered from having large families without adequate resources.

10. After retiring in 1970, Clark continued to fight inequality and serve her community.

In 1976, she won the back pay and pension that was denied to her when she was fired from her South Carolina teaching job in 1956 for being a member of the NAACP.

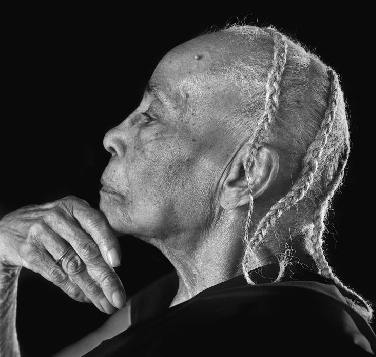

Clark in her later years

http://www.laurietobyedison.com

She served on the Charleston County school board from 1975 – 1978, when she was nearly 80 years old.

Big thanks to Zinn Education Project for this post idea. Check out their page on Clark’s book Freedom’s Teacher, and their teaching materials on the civil rights movement!

Sources

Interviews with Jaquelyn Hall (1, 2)

King Center

AKA Authors

U of South Carolina — Aiken

Safero

StateUniversity

Wow, what an amazing person! I hardly knew anything about her before.

Pingback: Let’s Hear it for the Heroines | Those Who Teach

Pingback: Septima Clark, Black Educator Hall of Fame - Philly's 7th Ward

Pingback: Black Educator Hall of Fame: Eduactivist Septima P. Clark