The philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote: “The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people so full of doubts.” Whether on a local or global level, the problems we face require the best people to step up. But many hold back because they feel that luck rather than ability lies behind their successes, and dread that sooner or later some person or event will expose them for the fraud that deep down they believe themselves to be. Far from being a realistic self-assessment, the impostor syndrome mind-trap prevents people from believing in themselves, to the detriment of us all.

As a life coach, I work with people who sense they have more personal and professional potential but feel blocked from fulfilling it. For some, hearing about impostor syndrome for the first time is a revelation. They realise that, far from it being their own shameful secret, it is a recognised phenomenon, first identified in 1978 by psychologists Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes.

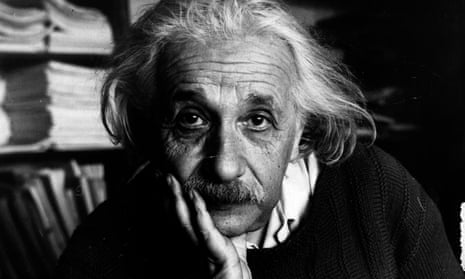

According to some estimates, up to 70% of successful people have experienced impostor syndrome, including Maya Angelou, Albert Einstein, and Meryl Streep. Unlike other forms of anxiety that sap confidence, the syndrome’s insidious nature means that external success heightens rather than soothes the effects, as sufferers believe they are only ramping up the confidence trick they are playing on everyone.

I am well acquainted with the sleepless nights before a presentation, the chorus of self-criticism even when I do something well, my tendency to explain away success, and the fear of being exposed. Fellow sufferers tend to overwork, people-please, and experience toxic stress and depression. But rather than pushing our anxieties to the back of the emotional inbox and soldier on, I invite us all to lean in. If you spot the symptoms then you have a great opportunity to develop self-awareness, generate pragmatic empathy, and integrate practices that will support you to live a more fulfilled life.

First, know that it’s not entirely your fault; evolution is partly responsible. We are all the descendants of worriers. Any strain of homo sapiens who were not would have died out millennia ago. Survival of the fittest means all humans live with degrees of anxiety – including the kind that can cause impostor syndrome.

Second, your culture will also have an effect. As a coach, I have noticed that British clients are less inclined to own success for fear of being labelled arrogant, compared with Americans. Women and people from minority populations also experience impostor syndrome more, due to cultural inequities.

Third, as children our emotional need to belong often leads us to downplay our abilities as a survival strategy, believing we are more acceptable when we fit in rather than stand out. This can linger into adulthood where it harms rather than helps us. But while we may not be sole authors of our anxious tendencies, we do have responsibility to do something about it so that we can serve ourselves and the world better.

Next time you fear being exposed as a fraud, name it for what it is – impostor syndrome. Notice the cascade of bodily sensations and automatic thoughts. Perhaps your stomach flips or heart pounds. What are the scripts that your mind starts running? They will be the same ones again and again, which makes them easier to spot: “I’m useless and people will know”, for instance. Remind yourself that this is not reality, just your perception of it. To name impostor syndrome is to start to sense control over it and recognise that it is a complex condition that you can – with practise – overcome.

Give each inner script a character so you can recognise who is speaking when they pipe up: “the judge” or “the perfectionist”, for instance. They are mechanisms of your subconscious running the same program as when you were a child, working to keep you in your comfort zone where you feel you can manage and be accepted. They often show up when you are taking on more responsibility, challenges and risks.

Talk back to them, thank them for services rendered and instruct them that they are surplus to requirements. In parallel, tone up your connection to your inner allies: the inner psychological sub-personalities of your brain’s executive function who encourage and coach you. Name them too: “the sage” or “the inner leader”. Though it might feel odd, you are externalising your negative thoughts and tapping into your inner wisdom, clarity, courage and compassion.

Have the courage to be imperfect. Our increasing impatience with ourselves seriously depletes our ability to recognise that we are works-in-progress, moving along learning curves all the time. We tend to freeze the frame when we feel nervous, make a mistake or have to sweat to achieve something, and then we damn ourselves for not being up to the job.

Finally, take some time to clarify your values. When you know what you stand for, you know what you uniquely have to offer so you won’t pretend you are something you are not, just to get along. Impostor syndrome can be a gift if you use it to create more helpful, mindful, less toxically stressful ways of living. When people share with others who know how they feel, the sense of isolation and shame falls away, and self-awareness, connection and empathy grow. Then we can step forward.