Not a day goes by that pundits aren’t bemoaning the struggles of the drug industry: R&D productivity declines, FDA uncertainties, restructurings and downsizings, payor and reimbursement dynamics, pricing pressures, generics and patent cliffs, etc… Many critics worry about slowing growth in demand and even decline in the branded drug industry due to these issues. The list of challenges is seemingly endless, and they are certainly significant.

But there’s a few of us who believe we are about to enter a secular bull market for Pharma based on three key macro drivers: wealth, health, and medical efficiency. Using data and insights from Tim Opler at Torreya Partners, this post lays out how these three support a strong positive case for the attractiveness of Pharma industry (which includes biotech and pharma for the purpose of this discussion) over the next couple decades.

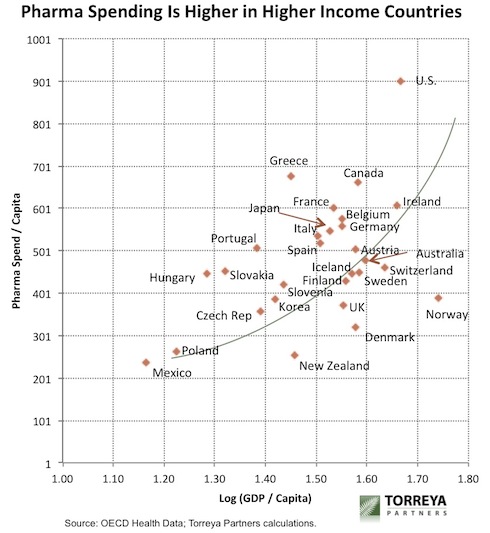

- The wealth effect. More wealth per capita correlates with higher Rx consumption. The US, Japan, and western Europe have been the bulk of growth in Pharma demand for decades, but this is clearly changing. Society’s willingness to spend on medical care and pharmaceuticals in particular are primarily driven by wealth, and demand for Rx has historically risen disproportionately with income. As presented in the chart below, there is a strong positive nonlinear relationship between Pharma spend and GDP, and this cross-country data is in line with US data over time. In short, drug spend has an income elasticity of demand greater then one: once consumers or society have covered life’s basic needs, they channel more spending towards premium goods like investments in life extension and better quality of life. Right now, the world, with the rise of the BRIC economies in particular, is becoming wealthier and the resulting rise in income will drive greater pharmaceutical use. Especially as western economies slow their growth in the ‘new normal’, the demand from the rest of the world will disproportionately contribute to Pharma’s growth.

- Healthier living leads to longer lives. Longer lives will drive Rx demand. Life expectancies have gone up across the globe over the past 50 years, in large part due to better access to healthcare. In the west, cardiovascular interventions have had an impressive impact, as have infectious disease treatments. Instead of succumbing to one’s first heart attack, many now live on for decades with appropriate medical care. HIV is now almost a chronic condition rather than a death sentence. The trend towards longer lives will almost certainly continue, and as Torreya projects below nearly 7 more years (~10% longer) will be added to developed economy life expectancies by 2039. Its far greater in the rest of the world. As people live longer, demand for more care to keep them healthy will undoubtedly grow, especially treatments for age-related diseases (Alzheimers, AMD, cancer, bone, cardiometabolic, pysch, etc..). This demand is also likely to be non-linear: holding aside the acute care burden of the last couple years of life that will likely still exist, adding 10% more “healthy” living will extend what are the very high consumption years for Rx within healthcare.

- Drugs can offer a powerful, efficient delivery of care. High impact therapeutics help keep people healthier and prevent expensive acute care in hospitals. Statins and blood pressure medicines have had a huge effect of cardiovascular health; ulcer medicines have prevented expensive interventions (e.g., anyone do vagotomies any more?). Gleevac is nearly curative for CML. There are tons of examples. Not only do drugs have great value for improving survival and quality of life, they are also incredibly cost effective relative to many other interventions by the system. Especially in aggregate where generics for older, effective medicines help lower the average cost considerably. But today less than 15% of healthcare costs go for pharmaceuticals. Why shouldn’t pharma consumption be more like 25% or higher of overall costs by 2020 or 2030? Its not how much we spend, its how effective the spending is. In many emerging markets, drug spend is and will likely continue to be far higher as a percentage of healthcare costs as they seek these less acute, cost effective solutions. Over the next few decades I have no doubt that pharmaceutical spending will become a far greater part of the overall healthcare spend with beneficial impacts on society.

So the macro forces for increased demand and revenue growth are clearly in the pharma industry’s favor.

Now there’s at least three areas which could drag down this bull market potential that I think are worth commenting on, but frankly each could also help accelerate it they unfold in a favorable way.

Pricing. Pricing pressure certainly exists, but again there’s no evidence to believe that high value products will not be able to command premium pricing. However, as an industry, we need to get real on pricing and stop thinking that oncology products that extend lives by months should cost $50K for a course of treatment. This is ridiculous. And the Avastin-Lucentis saga for AMD borders on the absurd. But at the same time, industry and society both need more openness to value-based pricing. Some orphan and specialist drugs cost what they do because they offer significant medical benefits (like longer term survival!) to a small group. This makes sense. Furthermore, pay-for-Rx-performance models will continue to emerge and are a good thing: if the drug works, Pharma gets paid. If not, no payment. Tools to pick the right patients are key for the economics of these models, and we’re seeing more of them (kudos to the FDA for approving the recent B-RAFi + diagnostic for melanoma). This more personalized patient approach will also support higher value-based pricing with pharmacoeconomics allowing higher premiums.

Regulatory. Risk needs to be weighed by the relative benefit. We can’t raise the bar to infinitely high standards of safety if the drugs offer real medical outcomes to large subsets of patients. Obesity and diabetes drug areas are a great and sad recent example here. But the FDA is in transition: its clear many in the agency, like Commissioner Hamburg, are trying to embrace innovation and change the culture. But at the same time safety lynch mobs post-Vioxx have been unleashed on many drug classes and often forced a narrow myopia around risk as a standalone parameter, forgetting the benefits. This clearly has to change. Phase IIIs large enough to find all the idiosyncratic risks are so prohibitively expensive as to kill innovation. Lastly, we need a clear path for accelerated, conditional approvals. Given the costs of big Phase III programs, patients (and smaller biotech) could benefit from post-Phase II accelerated approvals for novel drugs that could be confirmed on the market with larger Phase III/IV studies. We need more balance at the FDA, and we also need more public and industry support for the FDA’s current efforts to change.

R&D productivity. I have high hopes here and think the pundits have failed to appreciate the temporal constraints on R&D improvements. Any changes in drug discovery today won’t impact new drug approval rates for 10-15 years. As I noted earlier, most of the 1H 2011 drug approvals were discovered in the 1990s. Similarly, most of the big clinical failures of the past five years had their roots in the discovery strategies of the 1990s. So all the advancements in the 2000s on the early research side (e.g., predictive tox, improved PK/PD modeling, smarter libraries, new modalities) have yet to play out. I think many firms in the industry have seen an improvement in discovery and research productivity. The endless restructurings and mergers have definitely distracted many companies, and created a big brain drain, but the underlying intrinsic productivity potential of many of these groups has gone up, not down, from what I can tell. Finding the cash to fund these programs in a world where R&D spend is dropping is the challenge. Hopefully, the venture world can help by supporting externalization of many of these interesting assets. But I’d bet in 10 years we’ll see lots of great innovative stories approved that had their beginnings in the not-so-unproductive 2000s.

So to conclude – there’s a strong bullish case to be made for pharmaceuticals as a sector. With valuations at P/E levels far below historic averages, there’s a lot to pick from. And while this doesn’t mean every company will perform, the sector is likely to enter into a secular bull market with society, patients, and investors as the beneficiaries.