#JeSuisCharlie Movement Leveraged to Distribute DarkComet Malware

Analysis Summary

DarkComet malware found to be exploiting French-speaking targets and distributed using the #JeSuisCharlie hashtag.

Recorded Future found DarkComet distribution across hacking forums frequented by jihadist sympathizers and a variety of social media platforms.

Based on Recorded Future temporal analysis, threat actors compiled malware and began exploiting systems less than a week following the last terrorist attacks in France.

The #JeSuisCharlie malware campaign is the latest example of cyber criminals and nation-states taking advantage of offline crises for online malware campaigns.

Introduction

Immediately following the terrorist attacks in France this month, claimed by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the top cyber defense official in France reported hackers have hit about 19,000 French websites largely through defacements and denial-of-service attacks. While these attacks were relatively crude, information security firm Blue Coat discovered more sophisticated attacks were taking place using the DarkComet remote access trojan (RAT), a tool commonly used by criminals and other threat actors to maintain access and control infected computers.

Using #JeSuisCharlie to Spread Malware

Less than a week after the attacks in Paris on January 7, DarkComet malware was found in the wild specifically targeting French systems and spread using the #JeSuisCharlie hashtag. Once downloaded, users see a popup of a popular image, seen below, that is available online and commonly used in the #JeSuisCharlie conversation.

Figure 1: Popular image used in #JeSuisCharlie discussions dropped with the DarkComet malware.

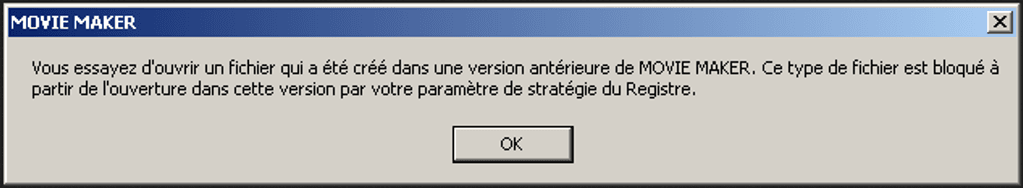

As users see the initial image, the malware also tricks the user with an error message that indicates problems with Microsoft Windows Movie Maker software, which comes pre-installed by default on many Windows OS systems. The error message translates to:

“You try to open a file that was created in an earlier version of MOVIE MAKER. This file type is blocked from opening in this version by your registry policy setting."

Figure 2: Fake French error message users encounter after downloading the DarkComet malware.

The error message indicates the malware campaign is specifically targeting Windows machines, given the likelihood Movie Maker comes pre-installed, and in French-speaking regions. The command and control network of the malware makes use of No-IP’s Dynamic DNS Update Client, a free tool often used with malware to ensure connection to infected systems. As shown below, the network used in the campaign also points to French-focused targeting. The #JeSuisCharlie DarkComet malware calls out to the dynamic No-IP domain and associated IPs listed here:

SNAKES63.NO-IP.ORG

78.248.17.59 – Free SAS France

86.216.158.194 – Orange S.A. France

86.216.157.158 – Orange France HSIAB

90.96.171.250 – Orange France GPRS Network

90.96.188.179 – Orange France GPRS Network

81.253.76.147 – Orange France HSIAB

The command and control details are a clear link back to French IP space, which reinforces the argument the malware is intentionally targeting French citizens, and the threat actors may also be of French-speaking background. However, this does not necessarily indicate the actors are from France.

Other regional actors, such as the Middle East Cyber Army (MECA) were active in #OpFrance following the attacks in Paris and there are others in areas like North Africa, particularly Algeria, where French-speaking threat actors are still hostile towards French targets. For example, the Kouachi brothers who carried out the attacks in Paris were of Algerian descent and crowd-sourced cyber attacks online, such as #OpAlgeria, have attracted thousands of followers.

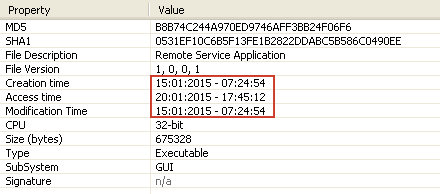

Looking at another common attribution factor, malware compile time, we can also see the quick turnaround these actors took in repackaging the DarkComet malware to target French-speaking targets. The malware was compiled about a week after the first terrorist attacks in Paris on the Charlie Hebdo offices.

Figure 3: Analysis of the malware shows a compilation date a week after the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks.

DarkComet in Use by Iranian Hackers and the Assad Regime

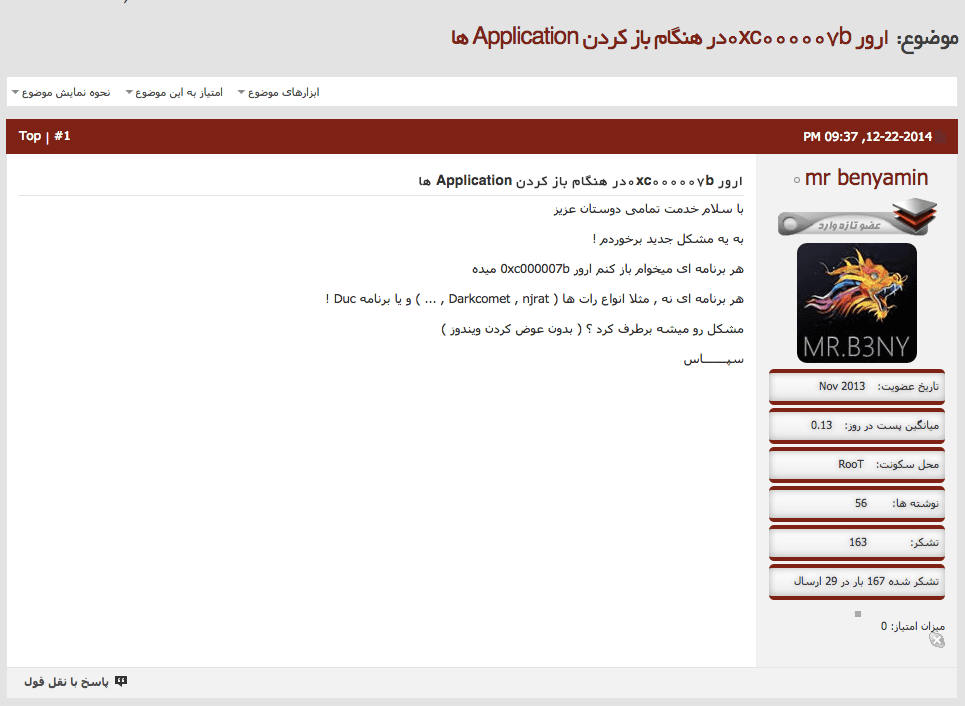

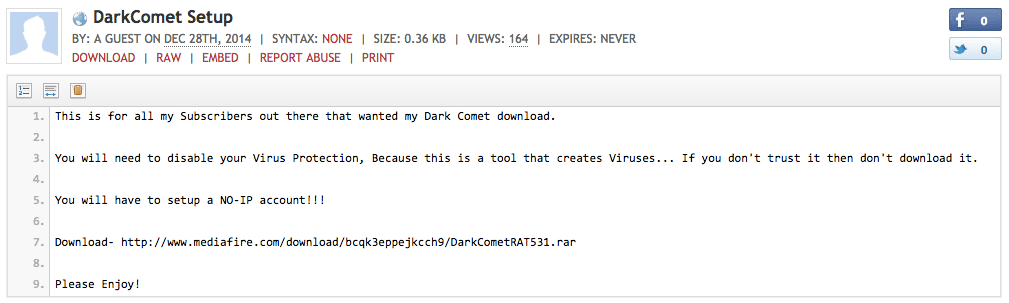

In the week prior to the terrorist attack and malware compilation, Recorded Future found discussions on proper use of the DarkComet malware on known Iranian hacking forum Ashiyane, which dubs itself “The First Security Forum in Iran.” Seen in Figure 5, forum member “Mr. B3NY” discussed troubleshooting a common error affecting 64-bit Windows software which they had not previously encountered when they successfully executed DarkComet and njRAT, another Remote Access Trojan that has been popular with criminal actors in the Middle East.

While there were no direct links found between the jihadist forums and the #JeSuisCharlie malware campaign, the crossover of interests between the terrorist attacks, malware campaign, and online jihadist actors is significant. As these situations continue to arise, there will likely be a continued shift from offline terrorist attacks to a second stage of online attacks that can take advantage of online solidarity to distribute malware and exploit systems.

Figure 4: Members of Iranian hacking forum Ashiyane discuss DarkComet and other tools.

Forum members also suggested use of the Dynamic DNS Update Client (DUC), freely available software that has consistently been a popular tool, as seen in cyber crime journalist Brian Krebs’s extensive reporting, for criminals to ensure access to infected despite IP changes.

Information security researchers from Symantec have analyzed the popularity of njRAT in the growing Middle Eastern cybercrime scene, and in particular the fact that it was initially developed and supported by Arabic-speaking actors. Given the growing ideological rifts online that mirror geo-political conflict offline, it’s interesting to see that actors on an Iranian hacking forum, which would be generally opposed to many Arabian cybercrime actors, are seemingly agnostic about the tools they use.

The trend of diverse actors appropriating cybercrime tools despite their source ties in with DarkComet as well, where it previously made headlines at major outlets like CNN when it was discovered in use against Syrian opposition activists in the current civil war. Since the discovery, the creator of the DarkComet malware suspended his personal distribution of the malware.

The use of criminal tools, in particular DarkComet and njRAT, by government or politically motivated actors has been significant enough that they both are included in the recently released Detekt tool which currently scans systems for malware families that are commonly used by government actors against opposition targets. Furthermore, DarkComet was also identified in Citizen Lab analysis as a common tool used by pro-Assad regime actors.

Wide Availability Prior to #JeSuisCharlie Malware Campaign

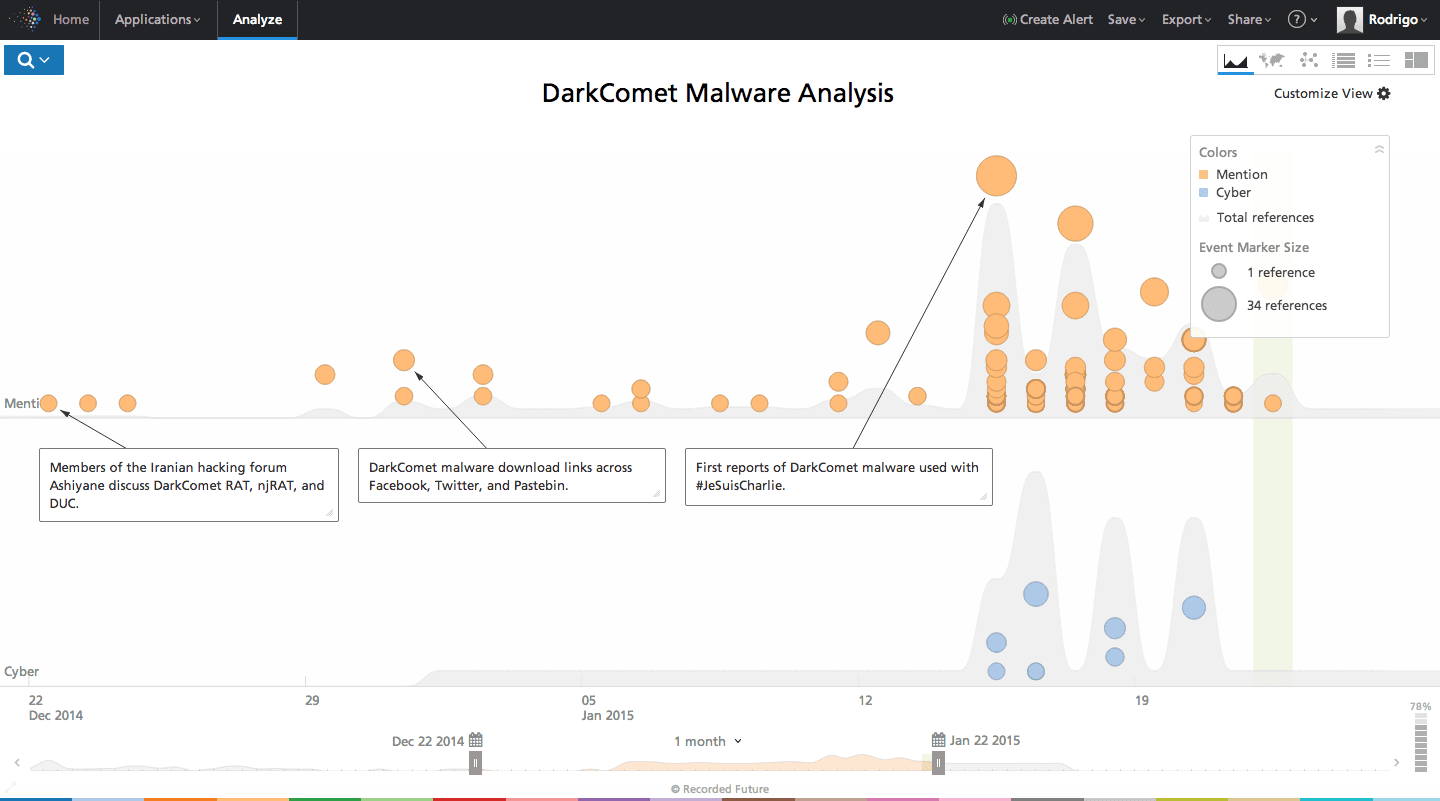

Figure 5: Recorded Future timeline of DarkComet malware references in the last month.

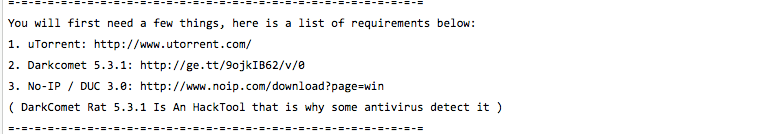

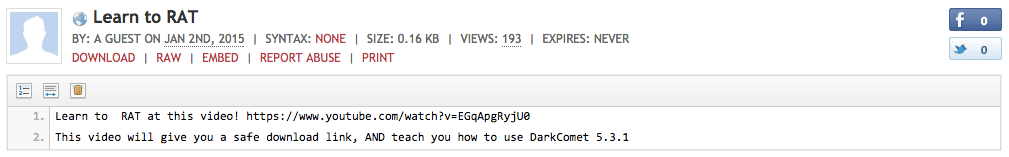

Recorded Future found the malware still freely available and promoted by a variety of sources with multiple download links mentioned on social media and hosted on Pastebin. The variance in download versions is possibly explained by the likelihood that some are backdoored by those offering them. Official development on DarkComet ended with 5.4.1, often referred to as “Legacy” version, and many open downloads for other threat actors to include their own backdoors have appropriated the malware.

Figure 6: Pastebin download links found on Twitter and Facebook with No-IP’s DUC tool and DarkComet malware.

Conclusion

The French-based command and control network, the French-language faked error message dropped with the malware, and the context of distributing using the #JeSuisCharlie hashtag all indicate a campaign specifically targeting systems in French-speaking regions. Given the common use of DarkComet among Middle Eastern actors from criminals to nation-states, there may also be a connection to political or ideological actors behind the campaign.

Recorded Future found no conclusive connections, but confirmed the tools are still discussed in known online jihadist forums and openly promoted as free downloads across a variety of social media, file-sharing, and paste sites. DarkComet and DUC are often used together by a variety of actors due to their free availability, but the context of the attacks in Paris and the carefully targeted malware may indicate a crossover of interests from offline attacks to online operations by jihadist sympathizers.

While the actors and intentions behind the campaign remain unknown, the precedent of using offline crises to craft targeted online attacks is significant. Following previous Recorded Future reporting on point-of-sale malware during the holiday season and online attacks using the MH17 airline tragedy to exploit users, the #JeSuisCharlie malware campaign represents the latest step in criminals and other threat actors leveraging solidarity in offline crises for online exploits.

Related