I am very cautious when hiking during thunderstorm season, especially above the treeline where there is no protection from lightning, hail, and high winds. I’ve just had too many close calls where thunderstorms have caught me out in the open and scared me half to death with their fury. While I can peacefully sleep through storms like this while camping at night, it’s a different matter to be caught out in the open with no place to hide.

While there is a chance that you’ll get beaned by a baseball-sized chunk of ice during a hailstorm, hit by flying tree branches, swept away in a flash flood (the number one cause of thunderstorm-related deaths), or zapped by ground current lightning which can travel hundreds of feet from the point of impact over roots and rocks, the best way to avoid these dangers is to avoid thunderstorms altogether.

Thunderstorm Warning Signs

The best way to avoid thunderstorms is to heed weather forecasts (if you have access to them) and sit out storms or hike during the hours when they’re least likely to occur. With a little experience, you can also accurately forecast the weather by keeping a close eye on cloud formations, wind speed, wind direction, or barometric pressure when hiking out in the open where the threat of lightning and hail is the greatest.

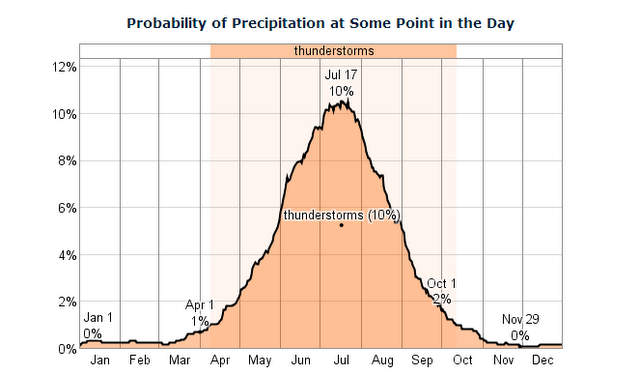

For example, in New England, thunderstorm activity is highly seasonal, occurring most frequently from June through August. If you plan on hiking or backpacking in this area during these months, make sure you build a bad weather day or two into your schedule in case you need to abort a hike because of dangerous weather. I’ve made the mistake of trying to push on in the past and it’s just not worth it.

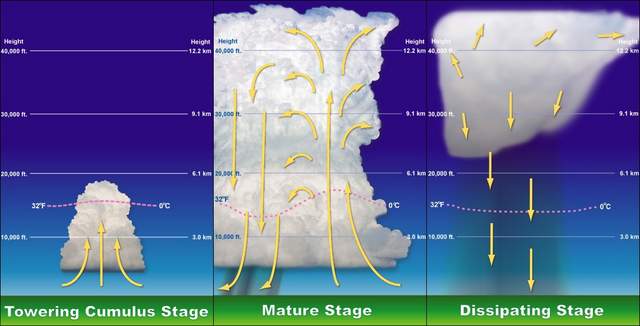

Most summer thunderstorms occur between noon and midnight when the sun has had a chance to heat up the warm moist air which rises to form a thunderstorm. If you do need to hike through an exposed or open area, it’s best to get an early morning start so you can get through it before the early afternoon hours before most storms reach a mature stage of thunderstorm formation.

If you can see the sky, you can also monitor possible thunderstorm activity by looking for large puffy cumulus clouds on the horizon. If they start growing very tall or anvil-shaped, you can expect a major thunderstorm. For example, I’ve been on hikes through highly exposed alpine areas where I’ve been able to see such clouds approaching me from 30 miles away. The sight of these clouds encouraged me to hike a lot faster and to get below the treeline before they arrived and let loose their full wrath!

If you remain alert to the weather when hiking and backpacking, there’s no reason you can’t avoid being caught in the open when a thunderstorm hits. Most thunderstorms only last for 30 minutes, and you can simply wait them out before proceeding with your hike.

SectionHiker.com Backpacking Gear Reviews and FAQs

SectionHiker.com Backpacking Gear Reviews and FAQs

As a canoeist, this advice goes double for those out on the water. A Lighting strike on the water of larger bodies of water can be deadly. You are often the tallest object on the water and can “draw” a strike. Use extreme caution.

Many moons ago I and three of my young nephews were on the PCT in the Laguna’s in Southern California for a day hike where we had the unique experience of being under one of these Anvil shaped clouds as it formed and then dumped about a half inch of rain and marble sized hail stones. We layed down on our backs in a meadow and watched as the clouds gathered above us and the resulting churning and turning and spinning and gathering darkness as the storm grew and got meaner and meaner. We got up and made it to our Parked car just in time when all heck broke loose and in an hour it was gone..Though there was a lot of lightening we did not see any cloud to ground strikes but the Cal.Div. Forestry fire trucks did go by us at one point but we never found out where they went..Thanks for a good informational piece.

up by 10am (summit). Down by 2pm (tree line). Has always been my rule of thumb when planning in the backcountry where weather reports are non existent, or areas that create weather themselves. Not a full proof guarantee but it helps to get it done early rather than praying that the rock you crawled under does not get cracked in half by a Zeus strike. Oh and tree line is not where the trees are the same height as you.

When hiking I keep my GPS receiver’s elevation plot set to barometric plat. I keep my GPS 62s powered on all day and if I see a trend of serious pressure change (diving down) that’s a good indication that the weather will be changing.

Dark, anvil shaped clouds are a great indicator of weather to come.

My go to resource is Jeff Renner’s book Northwest Mountain Weather.

Great post Philip, thank you.

Blake

Especially love the chart. Makes plain that summer is the main season for thunderstorms.

I would like to chime in as a weather enthusiast and also trained weather spotter. Anvil clouds typically indicate an already strong or severe thunderstorm. Towering cumulus clouds and cumulonimbus clouds do not need to “anvil out” in order to create a large amount of lightning and or heavy rain and hail. If you see cumulus towers going up, noted by their cauliflower like tops, be advised storms could be forming in your area. Make sure you always monitor forecasts prior to hiking, especially on multi day trips.