By Nicholas P. Money

The small picture is the big picture and biologists keep missing it. The diversity and functioning of animals and plants has been the meat and potatoes of most natural historians since Aristotle, and we continue to neglect the vast microbial majority. Before the invention of the microscope in the seventeenth century we had no idea that life existed in any form but the immediately observable. This delusion was swept away by Robert Hooke, Anton van Leeuwenhoek, and other pioneers of optics who found that tiny forms of life looked a lot like the cells that comprise our own tissues. We were, they showed, constructed from the same essence as the writhing animalcules of ponds and spoiled food. And yet this revelation was somehow folded into the continuing obsession with human specialness, allowing Carolus Linnaeus to catalogue plants and big animals and ignore the lilliputian majority. When microbiological inquiry was restimulated by Louis Pasteur in the nineteenth century, it became the science of germs and infectious disease. The point was not to glory in the diversity of microorganisms but exterminate them. In any case, as before, most of life was disregarded.

Things are changing very swiftly now. Molecular fishing expeditions in which raw biological information is examined using metagenomic methods have discovered an abundance of cryptic life forms. This research has made it clear that we are a very long way, centuries perhaps, from comprehending biodiversity properly.

Revelation of the human microbiome, the teeming trillions of bacteria and archaea in our guts that affect every aspect of our wellbeing, is the best publicized part of the inquiry. We are walking ecosystems, farmed by our microbes and dependent upon their metabolic virtuosity. There is much more besides, including the fact that a single cup of seawater contains 100 million cells, which are in turn preyed upon by billions of viruses; that a pinch of soil teems with incomprehensibly rich populations of cells; and that 50 megatons of fungal spores are released into our air supply every year. Even the pond in my Ohio garden is filled with unknowable riches: the most powerful techniques illuminate the genetic identity of only one in one billion of the cells in its shallow water.

Most biologists continue to be concerned with animals and plants, the thinnest slivers of biological splendor, and students are taught this macrobiology—with the occasional nod toward the other things that constitute almost all of life. Practical problems abound from this nepotism. Ecologists study things muscled and things leafed and conservationists worry most about animals, arguing for expensive stamp-collecting exercises to register the big bits of creation before they go extinct. This is a predicament of considerable importance to humanity. Consider: A single kind of photosynthetic bacterium absorbs 20 billion tons of carbon per year, making this minuscule cell a stronger refrigerant than all of the tropical rainforests.

Surveying our planet for its evolutionary resources, the perceptive extraterrestrial would report that Earth is swarming with viral and bacterial genes. The visitor might comment, in passing, that a few of these genes have been strung together into large assemblies capable of running around or branching toward the sunlight. It is time for us to embrace this kind of objectivity and recognize that the macrobiological bias that drives our exploration and teaching of biology is no more sensible than attempting to evaluate all of English Literature by reading nothing but a Harry Potter book. The science of biology would benefit from a philosophical reboot.

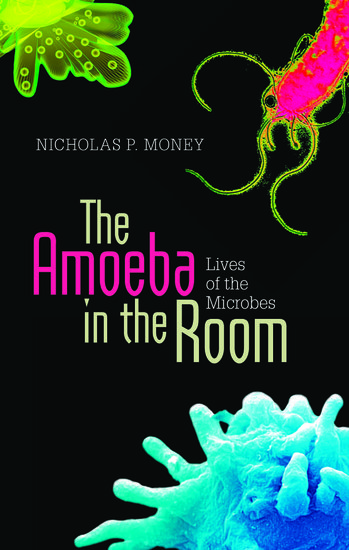

Nicholas P. Money is Professor of Botany and Western Program Director at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. He is the author of more than 70 peer-reviewed papers on fungal biology and has authored several books. His new book is The Amoeba in the Room: Lives of the Microbes.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Scanning electron micrograph of amoeba, computer-coloured mauve. By David Gregory & Debbie Marshall, CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0, via Wellcome Images.

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.