In Core v. Champaign County Board of County Commissioners, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio opined that telecommuting (i.e., work-from-home) might be an ADA reasonable accommodation under the right circumstances, but that case did not present those circumstances. The Core court specifically noted that the 6th Circuit does not “allow disabled workers to work at home, where their productivity inevitably would be greatly reduced,” except “in the unusual case where an employee can effectively perform all work-related duties at home.”

In Core v. Champaign County Board of County Commissioners, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio opined that telecommuting (i.e., work-from-home) might be an ADA reasonable accommodation under the right circumstances, but that case did not present those circumstances. The Core court specifically noted that the 6th Circuit does not “allow disabled workers to work at home, where their productivity inevitably would be greatly reduced,” except “in the unusual case where an employee can effectively perform all work-related duties at home.”

Yesterday, in EEOC v. Ford Motor Co., the 6th Circuit, for the first time, recognized that modern technology is making telecommuting a realistic reasonable accommodation option. The case involved an employee with Irritable Bowel Syndrome who could not drive to work or leave her desk without soiling herself. Ford declined her telecommuting request because it believed in its business judgment that her position—a buyer who acted as the intermediary between steel suppliers and stamping plants—required face-to-face interaction.

The 6th Circuit disagreed, in large part because Ford could not show that physical attendance at the place of employment was an essential function of her job.

When we first developed the principle that attendance is an essential requirement of most jobs, technology was such that the workplace and an employer’s brick-and-mortar location were synonymous. However, as technology has advanced in the intervening decades, and an ever-greater number of employers and employees utilize remote work arrangements, attendance at the workplace can no longer be assumed to mean attendance at the employer’s physical location. Instead, the law must respond to the advance of technology in the employment context, as it has in other areas of modern life, and recognize that the “workplace” is anywhere that an employee can perform her job duties. Thus, the vital question in this case is not whether “attendance” was an essential job function for a resale buyer, but whether physical presence at the Ford facilities was truly essential.…

[W]e are not rejecting the long line of precedent recognizing predictable attendance as an essential function of most jobs.… We are merely recognizing that, given the state of modern technology, it is no longer the case that jobs suitable for telecommuting are “extraordinary” or “unusual.” … [C]ommunications technology has advanced to the point that it is no longer an “unusual case where an employee can effectively perform all work-related duties from home.”

Like it or not, technology is changing our workplace by helping to evaporate walls. While telecommuting as a reasonable accommodation remains the exception, the line that separates exception from rule is shifting as technology makes work-at-home arrangements more feasible. If you want to be able to defend a workplace rule that employees work from work, and not from home, consider the following three-steps:

- Prepare job descriptions that detail the need for time spent in the office. Distinguish one’s physical presence in the office against one’s working hours.

- Document the cost of establishing and monitoring an effective telecommuting program.

- If a disabled employee requests telecommuting as an accommodation, engage in a dialogue with that employee to agree upon the accommodation with which both sides can live (whether it’s telecommuting or something else).

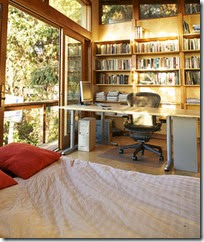

photo credit: Jeremy Levine Design via photopin cc