Polluted or pristine? Northern Everglades major factor in water struggles downstream

Randy Franey backed off the throttle of his Chicago Bear dark-blue airboat, swung the craft into a ditch and then blasted up a small embankment before coming to a stop and killing the engine along a far-flung stretch of the Kissimmee Chain of Lakes.

"You can’t beat the lifestyle. It’s nice and quiet," Franey said after dismounting his custom-built craft. "It’s just small town life. It’s not like Orlando with all the attractions, or the beaches. Nothing beats this country right here. It’s beautiful."

This is Franey's slice of the Everglades, a massive wetland system that stretches from the fast-paced, Mickey Mouse city of Orlando to the more relaxed and remote Florida Keys.

Many people think of the Everglades as only Everglades National Park (which is large at 1.5 million acres), but the entire system actually stretches across 16 counties and is home to about 8.5 million people.

It's mostly swamplands, severed by the occasional savanna, and home to various wading birds, snail kites, bald eagles, black bears and countless alligators.

More:Everglades restoration: Water storage, political will key to success

More:Everglades in 'worst' conditions in 70 years

This is where cattle line the banks of lakes and canals, where largemouth bass fishing is a way of life. It's a rough cut of Florida. Isolated. Alive.

Although the system has been greatly altered by man over the past century, it still is the lifeblood feeding a host of industries and activities in Florida, ranging from real estate to sportfishing. It's all linked: Water that falls on the Kissimmee system as rain eventually reaches Lake Okeechobee, the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie rivers, and Everglades National Park.

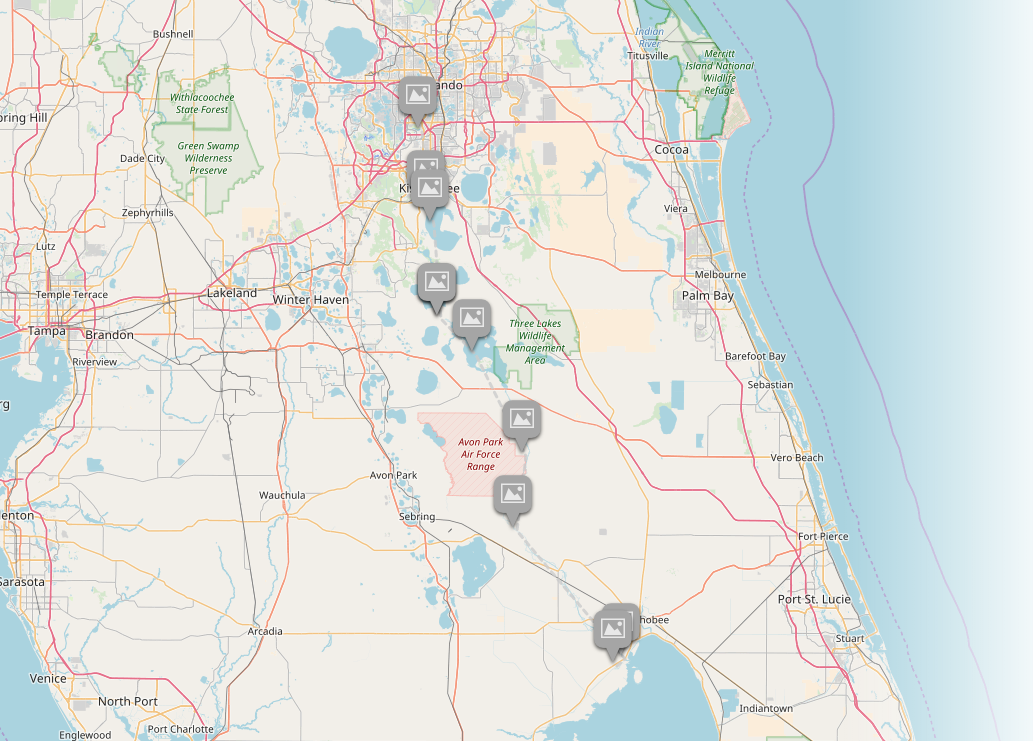

The News-Press sent a reporter and a photographer down the entire northern Everglades, from Shingle Creek to Lake Okeechobee, to find out more about the vast waterway, the people who live there and the water issues they face.

We also wanted to better understand the system and how water quality issues and challenges there impact water and lives here.

The headwaters of the famed River of Grass is a tiny slice of wetlands north of the 192 Flea Market and Walmart Supercenter in downtown Kissimmee.

"Shingle Creek (just outside of the Orlando area) is definitely the headwaters of the Everglades," Franey says while looking out over Lake Hatchineha. "And mankind has straightened the (Kissimmee) river and now they’re trying to get back to where it’s natural flow for habitat and animals, bird sanctuaries; and hopefully they continue with that effort because nobody likes a straight canal."

A vast waterway

Hatchineha is part of Kissimmee Chain of Lakes, all of which drain south into the Kissimmee River and eventually Lake Okeechobee.

It's not only the region where the system starts, but it's also where the water quality and quantity issues begin.

Historically, water flowed through the entire system uninterrupted, from Shingle Creek all the way to the Florida Keys.

But over the years man-made constructs have severed many of those natural connections while creating an artificial system that at times poorly mimics historic conditions in terms of ecological value, and water quantity and quality.

Now, instead of the lakes overflowing after large rain events and at the end of the rainy season, lake levels are managed to ensure there is enough water for large farming operations and the swelling populations along the coasts.

But some wonder what the future holds for this relatively undeveloped corner of the Sunshine State.

"You can't have a watershed that's that intensively developed and not have all kinds of water quality problems," said Linda Young, with the Clean Water Network. "It's good that they restored the Kissimmee, but it would take a lot, billions and billions of dollars of replumbing all the way north to Orlando, even if it's possible, to fix all the issues."

Nitrogen, phosphorus and other excessive nutrients from the upper system and washing off the local landscape sometimes feed coastal algal blooms, which can shut down swimming beaches, cause fish and marine mammal kills and impact property values.

"It's a concern for sure because there's incredible nutrient loading, fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, there's a lot coming from that watershed into the river and on down to the lake," Young said. "It sheet flows over the big pasture areas and will eventually run into ditches that will run into sloughs that will run into creeks that will run into the river."

Interactive map:Follow Chad Gillis and Andrew West’s journey through northern Everglades

The Chain of Lakes makes up the northern part of the system. From there the water flows through the upper Kissimmee, which has been channelized and turned into a big ditch.

Here the banks of the big canal are flanked by cow fields and the Avon Park Air Force bombing range.

Toward the south end of the Kissimmee system, the canal turns into a series of oxbows that have been restored over the past two decades.

Once a prominent feature of the entire river, the oxbows slow water down and help absorb pollution like nitrogen and phosphorus.

Improving conditions

The flood plain that is created after a heavy rainy season draws vast wildlife, which was one of the top reasons for restoring the Kissimmee River.

"The wading bird population was reduced to about 98 percent cattle egrets (a non-native species) and now we have 13 species of wading birds back," said Lawrence Glenn, with the South Florida Water Management District. "We have the full complement of wading birds that were there historically."

The $800 million restoration is expected to be completed in 2020 and will fill in about 22 miles of canals and will restore about 45 miles of the historic flow way.

Removing nutrients was not one of the main goals of the Kissimmee restoration, which started in 1999, but it has been a nice side benefit.

More:Rooney tours Everglades to gain support for restoration projects

More:Everglades Foundation: SFWMD reservoir to cut discharges won't clean water; ours does

Fewer nutrients flowing from the river and into Lake Okeechobee means there are fewer nutrients to release down the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie rivers.

"Any source of water, any tributary to Lake Okeechobee, is eventually going to be providing water to where it flows out of Lake Okeechobee," Glenn said. "So if reductions are made in those areas, that benefits the estuaries."

Paul Gray is an Everglades restoration representative for Audubon Florida and lives near the Kissimmee River.

Wildlife, he said, responded strongly to the restoration work.

"I think the overall goal is 80 wading birds per square mile and there are already 100 per square mile, and we’re not even finished," Gray said. "(The flood plain) fills with wading birds and eagles and jumping fish, it’s just wonderful to see. It’s really spectacular, and it’s what people think about when they think about Florida: these massive landscapes."

The oxbow work has remade much of the historic river, filling in the old canal and reshaping the river's banks.

"That water moves along very slowly and moves through plants and nutrients and sediments are being removed," Gray said. "So it’s a water storage and a water cleansing project."

But that's just one of several restoration projects that are being planned for the north part of the system.

Another goal is to raise the levels of three lakes by about a foot-and-a-half, which will allow more water to be stored north of Lake Okeechobee.

"This project was done to restore the river but it’s going to help (Lake) Okeechobee because all of that water doesn’t go into the lake," Gray said. "It’s equal to about 100,000-acre-feet, which is about 3 inches on the lake. But that’s 3 inches that’s not getting into the lake."

Less Okeechobee water during the rainy season, in theory, means fewer harmful releases to the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie rivers.

There are also plans to build water reservoirs and aquifer storage and recovery wells along the Kissimmee River and Chain of Lakes to help provide the needed water and the right times. These systems capture, treat and inject water into below-ground aquifers, where the water is stored until it is needed.

Pumps then pull the water back from the aquifer and put it back into the system to provide water for human consumption and for wildlife and the ecology.

"That’s why we’re trying to do these conservation easements because development is coming, and we want to lock up as much of this watershed in the habitat and condition it’s in," Gray said. "The cow pasture that’s there now, it’s only going to get worse with development."

Growth and pollution

About 7 million pounds of nitrogen flow into the Caloosahatchee River from Lake Okeechobee every year. That number jumps to 11.5 million pounds by the time the river water gets to the Gulf of Mexico, according to Florida Department of Environmental Protection records.

The 4.5-million gallon difference is attributed to farm fields north and south of the river as well as urbanized areas like Fort Myers and Cape Coral.

So where does all this nitrogen come from?

Depends on who you ask.

Sixth-generation rancher Cary Lightsey says the excess nutrients are coming from the developed areas at the far north of the system, from Kissimmee and the sprawling Orlando area.

"It’s runoff from roads and roofs and golf courses," Lightsey said while leaning against an oak tree on Brahma Island on Lake Kissimmee. "We think there’s just too many pollutants that they can’t control; and they’re going to continue to increase the population, so it’s going to be an endless problem."

While some people have suggested cattle owned by ranchers like Lightsey are a primary source of the nitrogen that eventually washes downstream toward Lake Okeechobee, Lightsey said that idea is bull.

"We’ve actually tested the intake and outtake, and it’s green vegetation," he said. "And nothing happened in that amount of time when it was going through their digestive system, there’s nothing in there that would cause a problem. And that’s been a concern of mine because we want to make sure we’re doing the right thing."

Cattle were first introduced to Florida during the 1500s, when the Spanish were exploring the area and trying to establish forts and missions.

"There’s always something that’s been grazing this land and it’s always (been) pristine," Lightsey said.

More:Lake Okeechobee reservoir to cut discharges now supported by some environmental groups

More:Lake Okeechobee discharges to St. Lucie River were 30 percent more than Army Corps reported

He says the problem is people, not cattle.

"Nothing ever changed until we got 10 million people here," Lightsey said. "There was a million head of cattle in Florida when the first million people were here and everything was fine. Now there’s 20 million people and still 1 million cows and now they want to blame it on the cows. The cattle are not a problem with the nutrients in the water. There’s no way they’re the problem."

Having trouble viewing the graphic?:Click here to view

Water quality scientists like Rick Bartleson, however, disagreed with Lightsey.

Bartleson works for the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation on Sanibel and monitors nutrient loads and water quality in the Caloosahatchee River and its estuary.

The Florida Department of Agriculture says there are hundreds of thousands of cattle in counties along the Kissimmee River and Chain of Lakes.

"Six hundred thousand cows, that's a lot of sewage that's not being treated that's flowing right into the river," Bartleson said.

While the cattle typically relieve themselves on dry land, rainwater washes those nutrients into the system. Again, that rain eventually works its way to Lake Okeechobee and either the Caloosahatchee or St. Lucie rivers or south toward Everglades National Park.

The United States Department of Agriculture says a 1,000-pound beef cow produces nearly 60 pounds of manure a day and just under 5 ounces of nitrogen. Multiply that 5 ounces times the number of cattle in Florida (just over 1 million) and you get 312,500 pounds of nitrogen being released from cows daily across the state.

Some of those nutrients are absorbed by plants before the water gets to Lake Okeechobee, and there are certainly other sources of nutrients in this part of the system.

Excess nutrients feed algae blooms and create a myriad of water quality problems, like what was seen here in the wake of the 2016 El Nino rains and after Hurricane Irma.

"The more nitrogen, the more micro-algae you can have," Bartleson said. "With the seagrass, the algae can cover up the seagrass blades, and you can get it just growing on the sand. It grows thick and breaks off the bottom and it washed onshore and causes low oxygen levels and turns things black."

The nutrients cripple the base of the marine food chain and, at times, severely impact the area's world-class coastal fishing.

"If you go to the (Sanibel) causeway now you see the grass is furry with algae, and the algae blocks out the light and keeps the plants from absorbing nutrients and oxygen," Bartleson said.

He said the nutrients build up in the estuary over time, and big events like major Okeechobee releases or a hurricane can stir those nutrients from the bottom and put them back into the water column – where they feed various algae.

"The sediments can be feeding those blooms for a long time," Bartleson said. "It's a big problem that we haven't got a hold of."

The News-Press interviewed several locals during the nine-day canoe trip down the Kissimmee River and Chain of Lakes, and many of them said they weren't overly concerned about water quality issues.

Some pointed to the world-class largemouth bass fishing as anecdotal proof that water quality is fine. If the fishing is good enough to draw people from all over the country, they argue, how can the water quality be that bad?

Then there are all the herons, egrets, snail kites and bald eagles.

"To sustain that kind of wildlife, it takes pretty good water quality," said Pierre Lavoi, who moved from the Toronto, Canada area. "It's still a lake for major fishing tournaments, so I'd say it's pretty healthy."

Others, however, say they've noticed changes over the past 30 or 40 years.

Gary Goudie, a retiree from Illinois, started fishing Florida lakes in the 1980s but stopped soon after because, he said, he was raising a young family.

But he retired recently, and started fishing again, this year at Camp Mack's along the Kissimmee River.

"I had concerns the first couple of days this week because there was so much algae floating on the water," Goudie said, while fishing the area in February. "It just didn't look healthy. I was surprised because it's been so cold. It's usually later on in the year when the water is warmer. It was so thick you could write your name in it."

Franey moved to this corner of the Everglades from Kentucky in 1971 and said he plans to spend the rest of his life along the river and chain of lakes.

"It’s a peaceful getaway from society and noises," Franey said as a fellow airboater roared up onto the hill and parked next to his boat. "I probably won’t leave this old place."

Connect with this reporter: Chad Gillis on Twitter.

Paddling with purpose

The News-Press is examining the vast water system that stretches from just south of Disney World to Florida Bay in the Keys. Experts say much of the dirty water flowing down the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie rivers comes from runoff north of Lake Okeechobee. So we sent a reporter and a visual specialist on a nine-day journey to trace the waterway from Shingle Creek near Kissimmee – the headwaters of the Everglades – to the top end of Lake O. The trip was part of a wide-range of reporting leading up to our second water summit on May 11. To see more of their journey, go to news-press.com.

IF YOU GO

What: Save Our Water 2018 summit

When: Friday, May 11, 8:30 a.m.-12:30 p.m. (Water Quality Fair and registration starts at 7:30 a.m.)

Where: Hyatt Regency Coconut Point

Tickets: news-press.com/saveourwater