It’s been an exciting year for new drug approvals, with the FDA on a similar pace to the gangbuster year of 2015. Many of these new medicines address significant and meaningful needs, or offer additional therapeutic choices for patients and physicians.

These new drugs also cover a broad range of indications: for example, in immuno-oncology (Imfinzi and Bavencio), Parkinson’s (Xadago), eczema (Dupixent), psoriasis (Siliq and Tremfya), multiple sclerosis (Ocrevus), and a number of different types of lymphomas/leukemias (Idhifa, Aliqopa, Calquence, and Besponsa). Several important ultra-orphan medicines were approved, too, including in mucopolysaccharidosis type VII (Mepsevil) and Batten’s Disease (Brineuria). All of this is good news for patients.

Even before the final month of the year, 2017 has by all accounts been a great vintage regarding the number of new FDA approvals. Beyond CDER’s conventional list of approvals (which most folks look at, sitting at 40 right now), CBER also approves a number of new medicines. This year we’ve had two very important CBER Office of Tissue and Advanced Therapy approvals, the CD19-directed CAR-T therapies, Kymriah and Yescarta. So collectively, we’re at 42 this year already, compared to 46 in 2015 (where Imylgic, Amgen’s oncolytic virus, was approved outside of CDER by CBER’s OTAT as well, but deserves recognition as a novel therapy). It’s worth noting that the FDA’s CBER division also approves a number of other agents all of us would consider “new drugs”, including all the recent long-acting hemophilia and recombinant blood coagulation products, but these aren’t included in traditional new drug metrics from the FDA.

As 2017 draws to close there will be plenty to discuss about this year’s cohort of medicines.

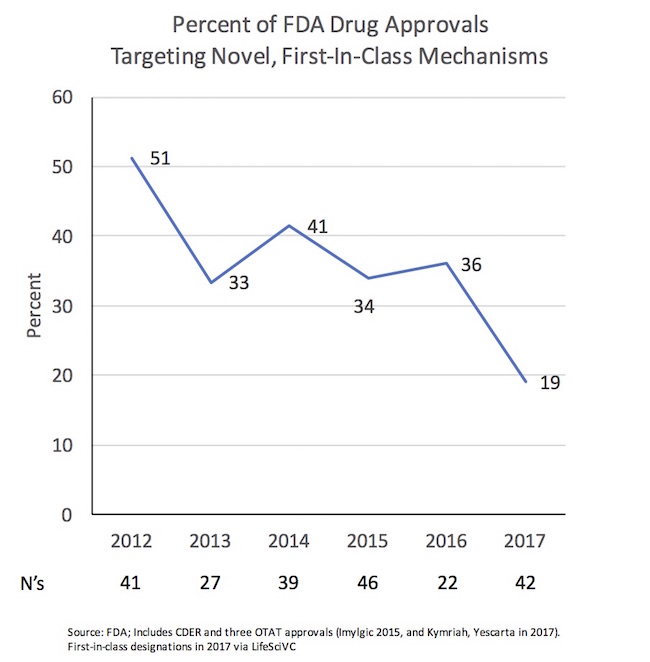

One of those themes is likely to the around their novelty, highlighting a striking observation: the negative trend in the proportion of first-in-class medicine approvals from recent prior years.

Since 2012, we’ve seen a decline in mechanistic novelty. From 2012-2016, one-third to one-half of all approvals targeted novel, first-in-class mechanisms of action. Even including the handful of precedented hemophilia/coagulation products approved during those years doesn’t fundamentally alter the percentage of novelty.

In contrast, so far in 2017, we’re running a just above half that rate: only 19% of the new drugs approved are first in class. As examples of the more precedented mechanisms with new approvals this year: PD1-axis, PARP, VMAT2, BTK, PI3K, ALK, IL6, IL17, CD20, MAOB, Azoles, Penams, etc… All great targets with demonstrated value to patients, but certainly not “novel” by first-in-class standards and well-represented with other on-market agents.

This could just be an effect of small numbers – the denominator is only 42 right now. Sample size is always an issue for analyzing annual FDA approvals.

But what if this is a trend rather than a statistical blip: could this change reflect the increasingly competitive nature of Pharma around targets that “work” in specific diseases? As an industry, we’re all working on the same targets in many disease areas. I’ve blogged on this topic before: in 2012, with the March of the Lemmings around a core set of cancer targets, and in 2016 on the Supernova-like explosion in immuno-oncology programmatic acitivty (PD1 in particular), to highlight two posts.

If this hypothesis is true – or even partially so – it has several implications:

- Shorter “single-product” life cycles are likely. In the past, first-movers often have had several years to build up their “ownership” of the class without competitors; only then would fast-followers appear and challenge their market presence. Today it appears as if first-movers are more likely part of a wave of similar approvals (Keytruda was first, but Opdivo and others were nearly simultaneous; PCSK9 had two approvals within months; PARP had several in the first year or so).

- Creative clinical strategies will increasingly be important for differentiation. In a world where competition emerges right away, clinical strategies will be critical for differentiating the label in crowded classes. We’re seeing differences in the trial designs shift share in classes like PD1s. Clever patient subsets and footholds in new populations will be important as beachheads for both first-in-class and best-in-class (or best-in-subset) molecules. In short, having a world-class clinical development capability – and creativity – will be an even more important differentiator of large players in biopharma.

- Competition on pricing amongst innovator products may actually become the norm. Historically, price competition amongst innovator products has not really been the case until late in the life cycle (like insulins today), but this could now happen at or near launch. Take the CAR-Ts recently: Novartis’ Kymriah priced at $475K with a unique pay-for-performance model, considered “low” by analysts; a few weeks later, Gilead’s Yescarta undercut that with a price of $373K (though lacking the pay-for-responsiveness feature). In different indications, these prices will play out in a meaningful way to alter the market position of different CD19 CAR-T products, I suspect. Only time will tell. But competitive pricing at launch seems common: Regeneron coming in at “only” $37K for Dupixent in a class where other biologics are $50K (here) is a sign this may be happening in crowded larger-market indications, too.

In sum, there’s much to celebrate in 2017’s new drug approvals. Kudos to the FDA, and to the industry sponsors. Will be interesting to watch the trend on novelty as we head into the last few years of this decade.