Content from the Brookings-Tsinghua Public Policy Center is now archived. Since October 1, 2020, Brookings has maintained a limited partnership with Tsinghua University School of Public Policy and Management that is intended to facilitate jointly organized dialogues, meetings, and/or events.

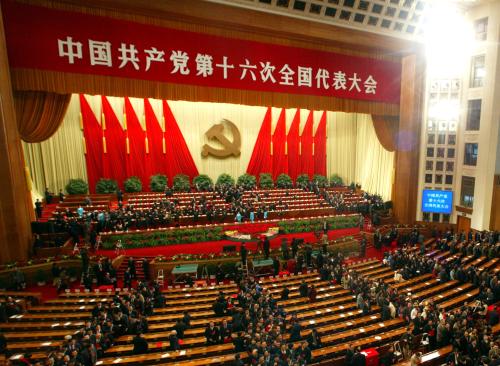

The Chinese Communist Party will hold its twice-per-decade party congress this fall to select its leaders for the next five years. Ryan Hass argues that the most likely outcome of the party congress will be policy continuity, not change. This piece originally appeared in Nikkei Asian Review.

The Chinese Communist Party will hold its twice-per-decade party congress this fall to select its leaders for the next five years. In the coming weeks, much ink will be spilled speculating about President Xi Jinping’s grip on power and his policy priorities for his second term. There have been predictions that when the politically fraught party congress is behind him, Xi will have sufficiently consolidated power to be in a position to embrace social and economic liberalization. Such forecasts belie experiences of the past five years. The most likely outcome of the party congress will be policy continuity, not change.

In the run-up to the last party congress in 2012, Xi similarly was a vessel for the hopes of numerous groups. At that time, Chinese intellectuals saw in Xi a bold leader who could deliver political reform. Entrepreneurs viewed Xi’s background in advanced regions like Zhejiang and Shanghai as evidence that he would champion economic liberalization.

Chinese leftists hoped Xi would draw ideological inspiration from Mao Zedong. Buddhists surmised that his family’s familiarity with the Dalai Lama might beget a more conciliatory approach toward Tibet. Members of the People’s Liberation Army anticipated that Xi’s experience as a secretary to the minister of defense would translate into support for a stronger military role in policymaking.

Even opinion leaders in Japan, Taiwan, and Hong Kong made cases for why Xi would provide a moderating influence on Beijing’s policies in these areas. With the benefit of hindsight, it is apparent that Xi was not beholden to any of these groups. For a variety of reasons — structural, political and ideological — the surest bet is that the same will hold true following the 19th party congress.

Above all, the Chinese political structure is not likely to undergo a dramatic transformation. Although Xi clearly prefers to be the first with no equals in the leadership structure, he also has been mindful to operate within — and not apart from — prevailing rules and norms. Xi is not likely to dismantle the system of collective leadership that was established by Deng Xiaoping to guard against a return to the power excesses of Mao. To do so would risk sparking a heated internal battle that would suck up all of the oxygen in China’s political system, leaving no space to advance other priorities.

Over the past five years, the Chinese leadership’s top priorities have proven extremely consistent, reflecting a consensus on broad goals. The leadership has remained steadfastly focused on strengthening the Communist Party, safeguarding stability, and enhancing China’s regional leadership and global standing. There have been changes to the manner in which Xi has centralized power and the party has headed off domestic and external challenges. But on the top priorities, the party has followed consistent north stars to guide policy.

Stability is key

To this end, the Chinese leadership will continue to emphasize financial and economic stability and guard against financial shocks. Particularly with the much-anticipated centenary of the founding of the Communist Party in 2021, Beijing will be determined to achieve its goal of becoming a “moderately well-off society,” which in practical terms means doubling per capita income and national gross domestic product from 2010 levels.

Over the past five years, when confronted with choices between greater control and greater openness to innovation, China’s leaders consistently have opted for the former. Expect economic policies to continue favoring state control and stability, even at the cost of some economic growth. This bias is likely to extend to policies related to the internet and social media, where heightened censorship over the past five years has demonstrated the leadership’s wariness of losing control of information in the digital age.

Likewise, the Chinese leadership will remain opportunistically proactive in pursuing China’s identified foreign policy interests, even when doing so generates friction with neighboring countries and the U.S. The one exception to China’s growing assertiveness is North Korea, an issue in which Chinese leaders have been — and likely will remain — mired in internal debate over how best to prevent conflict and preserve stability. Until that longstanding internal debate is resolved, Chinese policy will default to remaining narrowly and cautiously focused on urging all parties to avoid escalating tensions.

Under Xi, China’s energetic efforts to defend its sovereign claims and elevate its voice on matters of global governance have been well-received inside China. Such activism supports a narrative that China is reclaiming its past glory on the world stage. Particularly amid a declining rate of economic growth and endemic challenges such as widening wealth disparity, environmental degradation, and limited employment for recent college graduates, the popular belief in China’s rise offers a unifying source of pride for Chinese citizens.

While many of the names and faces at the apex of the party leadership will change this fall, the underlying objectives of the Chinese political system will not. Xi will continue to view himself as the principal protector of China’s established political order, and he will keep the leadership focused on meeting the benchmarks the party has set for its centenary celebration in 2021. Both the experience of the past five years and an analysis of China’s aspirations over the next five years support the expectation that there will be more continuity than change in China’s approach to domestic and foreign affairs following the party congress.

Commentary

Op-edNavigating China’s post-congress landscape

August 14, 2017