Why your 401(k) can be a cash drain

Everyone's heard of stretching to buy a McMansion and becoming "house poor." But what about saving too much for retirement and ending up "401(k) rich and cash poor"?

Don't snicker.

It can and does happen — often to investors with both good savings habits and good intentions for their financial future. These model savers later run into a cash crunch because of unexpected expenses, ballooning lifestyle costs or miscalculations.

Most personal finance pros advise U.S. workers to save as much as they can by stashing money in 401(k) retirement accounts, which lower taxable income and shelter investment earnings from the IRS. But there's a downside to tying up too much cash in these accounts: it could leave you without enough money for unexpected bills.

Learn more: Best debt consolidation loans

"Oftentimes investors box themselves in — in terms of future financial options — by worshiping solely at the altar of tax-deferred retirement accounts," says Tony Ogorek, founder of Buffalo-based Ogorek Wealth Management.

The error over-savers make is failing to put their finances through a stress test. By imagining your own financial crisis, you learn whether your cash flow is sufficient to cover expenses without tapping your retirement savings. And that knowledge is crucial because there's a heavy penalty for borrowing from your 401(k). Most accounts charge a 10% early-withdrawal penalty for people belowage 59 1/2.

"The main mistake," Ogorek says, "is not doing a realistic assessment of what your cash needs could be under various scenarios."

Of course, the bigger retirement crisis is Americans not saving enough, or not at all. Only about one-third of workers are saving in a 401(k) or a similar plan, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Still, putting every savable dollar into a retirement account may not be textbook planning.

The downside of too little cash for an unexpected car repair or a sports tournament 500 miles away is that investors are often forced to treat their 401(k) like a piggy bank or slush fund.

They do this by borrowing money from that account via a loan, then paying themselves back with interest. Or they withdraw all of their 401(k) money, which often triggers a fee as well as a tax hit on gains.

Planners note, however, that taking out a loan and paying yourself back is often better than using a credit card with an 18% interest rate to make ends meet. They warn, however, that if you get fired or switch jobs you will have to pay your 401(k) loan back immediately, which could lead to default.

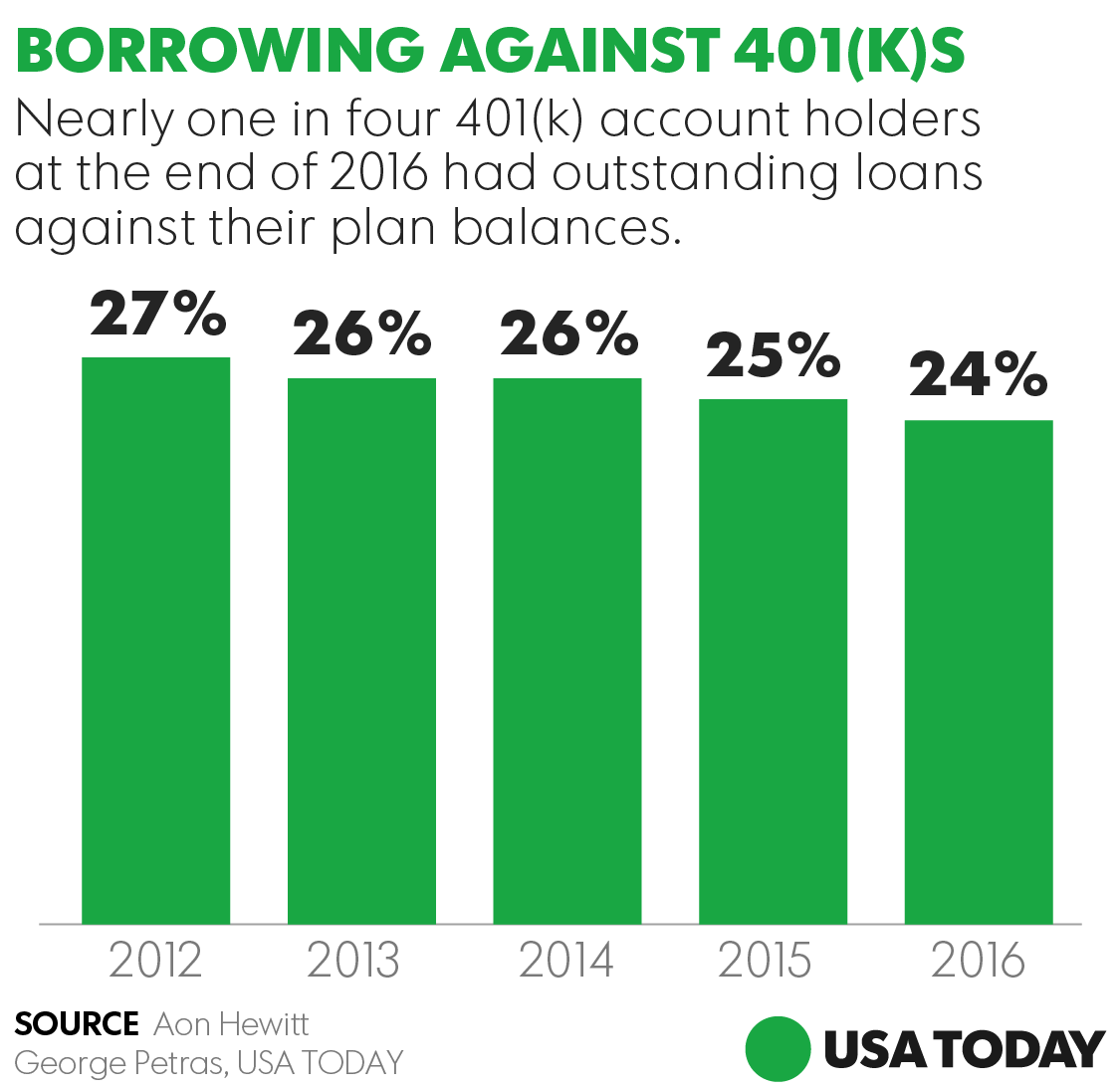

Last year, nearly one in four (24%) 401(k) investors had outstanding loans tied to their accounts, with an average loan balance of $9,225, according to Aon Hewitt, a human resources consulting firm. "Nearly $1 of every $5 saved is now outstanding as a loan," says Rob Austin, the firm's director of retirement research.

At the end of 2016, Americans had $7 trillion invested in employer-based defined contribution plans, including 401(k)s, and $7.9 trillion in IRAs, according to the Investment Company Institute, a fund-company trade group.

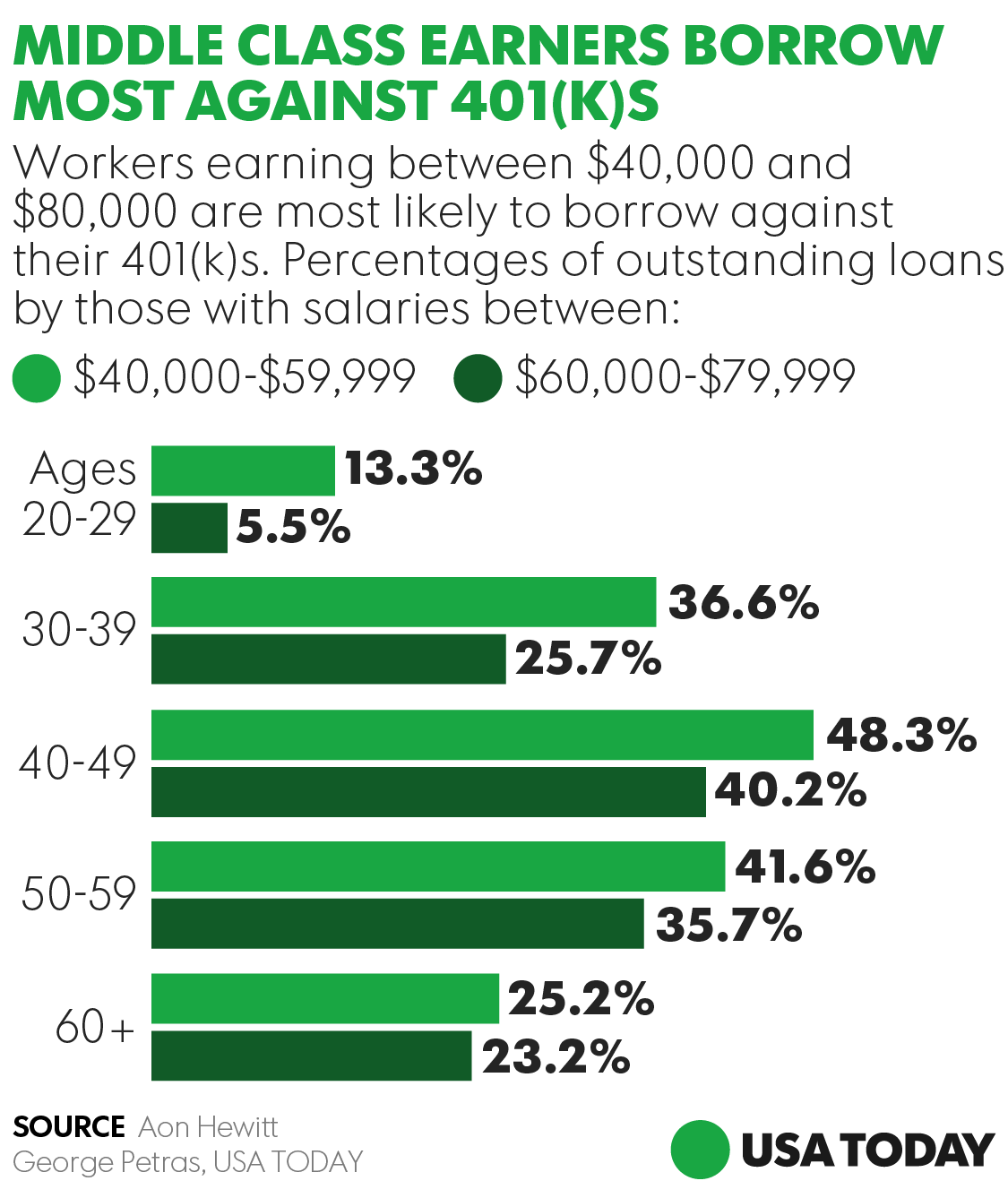

The middle class — or those earning between $40,000 and $59,999 — borrow most frequently from their 401(k)s. Nearly half (48%) of 401(k) investors in that income group between ages 40 and 49 have outstanding loan balances, according to Aon Hewitt.

While there's no way to quantify the number of people who took out the loans because their worth was tied up in 401(k)s, anecdotal evidence suggests that was the case for many.

Roger Young, senior financial planner at T. Rowe Price, says he occasionally saw that problem in his prior job as a financial adviser. "I certainly had clients that had the vast majority of their financial assets in a tax-deferred retirement account," he says. "You certainly don't want to be cash poor" in the years before retirement.

Often,he advised clients to do a better job covering all their financial needs by rejiggering their savings, mainly by diverting some money away from retirement accounts and into other savings vehicles.

Young advises people to use the following strategies:

1. Build an emergency fund. Stash away three to six months of living expenses so you have cash on hand to deal with crises, such as a job loss, major appliance breakdown or for a down payment on a car.

2. Open different types of accounts.Fund accounts that address different savings needs, such as cash emergencies, saving for college or a home, or health-care costs. "If you run into an issue, you have flexibility," Young says. "You want money in accessible accounts, such as a money market account or a taxable brokerage account where you can invest but where you can still gain access to your money pretty easily," he adds. Younger investors should consider investing in a Roth IRA or Roth 401(k), as the savings are deducted after-tax, giving investors more flexibility to withdraw money without a penalty.

3. Control your spending. Expenses have a way of growing over time. Costs for youth sports for the kids, academic expenses and home maintenance not only add up, but they often hit at the same time. "The key is living within your means and having a high level of savings overall," Young says. "It doesn't have to be all in your 401(k)."