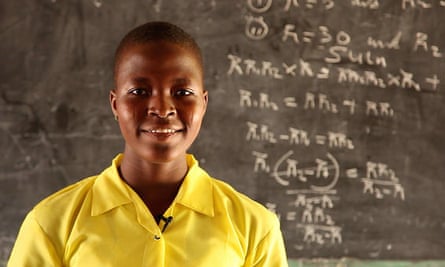

A few years ago, an outbreak of cholera and other deadly diseases swept through one of the poorest villages in the northern region of Ghana, taking the life of Ruhainatu’s mother, Jamila.

Ruhainatu was in her teens. A decade ago, Jamila’s death would have extinguished Ruhainatu’s chances of getting the education she needs to succeed in life. Instead of going to school, she would have taken on her mother’s role of caring full time for her home and family.

But efforts by the Ghanaian government, together with development partners like the Global Partnership for Education, have strengthened the country’s education system. Now Ruhainatu and girls like her have a more hopeful prospect for life. One of the top performing students in the local school, Ruhainatu has ambitions to go away to university to become a nurse and then return to her village to help others remain healthy.

Her story is one of countless affirmative real-life testimonials showing how educating girls can help them be healthier, more economically prosperous and become more civically empowered women. Their new knowledge can also improve the health and wellbeing of others around them.

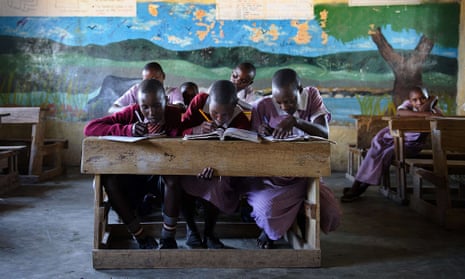

But enabling children to succeed requires the right combination of support, so that they will be healthy, well-nourished and can attend a quality school that has access to clean drinking water and toilets.

Providing school meals and deworming programmes, for example, can have an important impact. The 2016 Unesco global education monitoring report notes that school meals and deworming programmes promote better education outcomes, especially for girls. For very poor families, the prospect that their daughter will be fed means that sending her to school is a more attractive option than keeping her at home so she can attend to domestic duties, farm work or taking goods to market. Greater access to clean water can also translate into education improvements for girls, by reducing the time they take to collect water for the family and giving them more time for school.

This give-and-take between education and other social development factors has received more emphasis since the unveiling of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) last year. We are breaking down the silos that have historically divided development sectors. Education and global health groups now understand that improvements in each are essential to progress for both and we are already creating opportunities for deeper collaboration.

Now the evidence of what works is increasingly clear, let’s just get on with it and drive progress on the mutually reinforcing goals for global education (SDG 4) and gender equality and women’s empowerment (SDG 5).

For groups like the Global Partnership for Education, whose board I chair and which partially funded the program in Ghana that helped Ruhainatu, “getting on with it” includes continuing to support countries to close the gender gaps in their education systems.

Closing those gaps requires recognising and breaking down barriers to gender equality. Poverty is the biggest, but other significant factors include ethnicity, language, disability, early marriage, the distance from home to school, gender-biased pedagogy, fragility and conflict, absence of proper sanitary facilities, pressure to take care of family or earn money, and insecurity within and on the way to school.

We – in education or in any other related development sectors – could accomplish much more in less time if there was sufficient political support and enough financing. This includes first and foremost more domestic financing for education by developing countries themselves. But it also requires more donor funding. We can’t “just get on with it” when education’s share of overseas development aid has fallen from 13% to 10% since 2002. The International Commission for Financing Global Education Opportunities, notes in its just-released report that under present trends, only one in 10 young people in low-income countries will be on track to gain basic secondary-level skills by 2030. Clearly, this is completely unacceptable.

The Education Commission, on which I serve as a commissioner, advocates for a range of far-reaching transformations to improve education. The commission’s work provides new evidence on what works and costs out what it would take for the world to educate every child.

The call to action in financing is to increase total spending on education from $1.2tn (£0.9tn) per year today to $3tn (£2.3tn) by 2030. That’s a big jump but not an insurmountable one.

Making the leap starts with developing countries, donors, NGOs, the private sector and many others choosing right now to just get on with it.

Join our community of development professionals and humanitarians. Follow @GuardianGDP on Twitter.